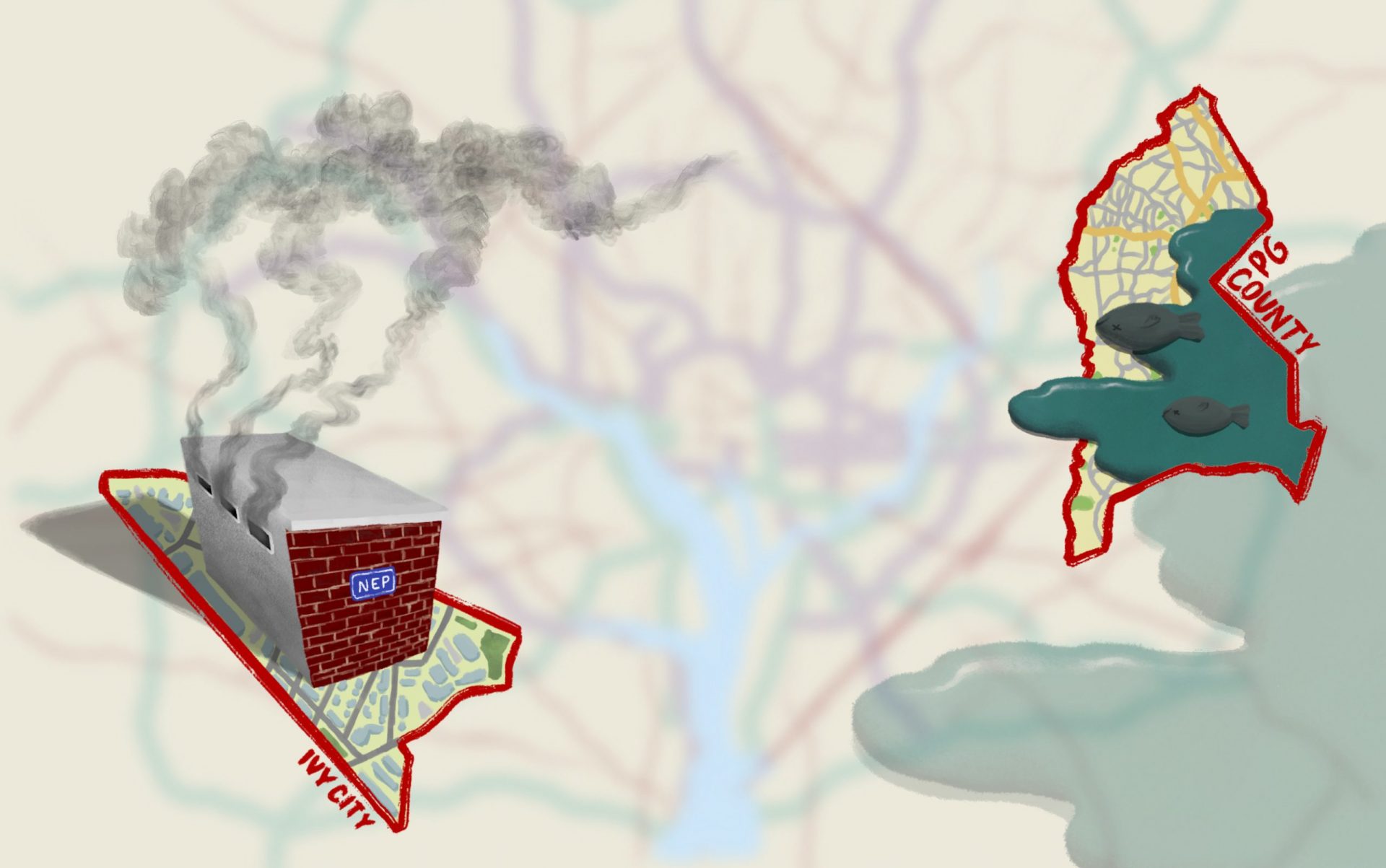

Residents of Ivy City, a northeast D.C. neighborhood, have reported a foul odor coming from an inconspicuous brick building since the 1930s. Though it looks unsuspecting, the building—a chemical plant for National Engineering Products Inc. (NEP)—produces high levels of formaldehyde and is polluting the predominantly low-income neighborhood with the release of cancerous substances into the air.

Advocates say this is just one example of a broader issue of environmental injustice in D.C.

“Why are they here? Why are they in our backyards?” Sabrena Rhodes, a resident of Ivy City, asked. “I realized that this place is a danger to our community, to the residents here, to my neighbors, and to the District.”

Rhodes is a community organizer at Empower D.C., an organization dedicated to advancing racial, economic, and environmental justice in D.C. For the last four years, Rhodes has dealt with various environmental issues in her neighborhood, including the NEP plant.

She began researching the company and its facility after a fire linked to the plant erupted in 2018. What she learned shocked her.

A 2023 study, commissioned by the D.C. Department of Energy and Environment, concluded that community exposure levels to formaldehyde and volatile organic compounds caused by the NEP plant exceeded safe levels outlined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Formaldehyde can cause difficulty breathing, trigger allergic reactions, and has been linked to nasal cancer. Volatile organic compounds like benzene and acetonitrile can cause cancer, damage to the central nervous system, and irritation to the eyes, nose, and throat.

“We are fighting for our lives. We are fighting for clean air, clean water, and clean soil in the nation’s capital,” Rhodes said.

What surprised Rhodes the most was that she, and many other residents in Ivy City, did not know about the chemical plant, as many community members saw the location as a non-descript “blank building.”

The NEP plant is attached to a residential home, much closer to residential areas than any modern zoning laws would allow. But because the plant has been in Ivy City since the 1930s, it hasn’t been subject to current zoning regulations. Rhodes and Empower D.C. are hoping to shut down the NEP plant or have it relocated to an area away from residential living.

To Rhodes, Ivy City is a key example of environmental racism. Environmental racism refers to situations where communities of color and low-income communities face disproportionately more environmental dangers than other communities. Ivy City is a historically Black neighborhood with households of mostly low and moderate incomes.

“Our community is a sacrifice zone,” Rhodes said. “We are the product of racist zoning practices.”

Addressing racial disparities, such as the inequitable policies and neglect in Ivy City, is an important aspect of environmental justice, according to Tim Bartley, professor of sociology and faculty member at the Earth Commons, a dedicated academic space for interdisciplinary solutions to environmental issues founded at Georgetown in 2022.

“Environmental justice is two things. Firstly, it’s the injustice of inequitable distribution of environmental hazards,” Bartley said. “Secondly, it’s the set of social movements and activist campaigns that have emerged to try to create a more equitable distribution of environmental hazards.”

Historic policy decisions have created lasting environmental impacts in cities across America, including D.C., that disproportionately affect Black and lower-income households. Bartley pointed to redlining as one example. The redlining practice involved banks and insurers denying loans to areas that they deemed “risky,” which were often those with higher numbers of Black residents. It resulted in the displacement of established Black communities and race- and income-based segregation.

“Redlining was one of a number of practices that created lots of residential segregation and also lots of inequalities of wealth and homeownership that set the stage for environmental injustice and environmental justice activism,” Bartley said.

While the practice has been illegal since 1968, the impact of redlining remains obvious in cities, including D.C. According to the D.C. Office of Planning, as of 2017 racial segregation was at 67%—meaning 67% of the Black population in D.C. would need to relocate to live in fully integrated neighborhoods with white residents.

A D.C. Policy Center report found that northeast and southeast D.C. have the highest levels of environmental pollution in the District, in part due to the disproportionate presence of highly polluting businesses located near these neighborhoods. These quadrants also have higher proportions of Black and low-income residents, partially as a result of redlining and other housing practices.

Rhodes said that Ivy City exemplifies how D.C. lawmakers and organizations overlook communities of color when creating and enacting environmental policy.

“If everyone was doing their job, we wouldn’t be having this conversation,” Rhodes said.

Beyond Ivy City, environmental racism is clear across the DMV, Dean Naujoks, a longtime member of the Potomac Riverkeeper Network, said. Naujoks is now a Potomac Riverkeeper, where he identifies and addresses sources of pollution along the Potomac and offers pro bono legal representation to sue polluters for violations of environmental regulations.

Naujoks said he has worked to develop an increased awareness of racial injustice in environmental policy, starting early on in his career when he worked in North Carolina.

Naujoks saw how hog farm pollution in eastern North Carolina disproportionately affected communities of color. When he moved to the DMV and started working on other environmental issues, he noticed the same underlying racial disparities manifesting in different ways, from improper waste management to water pollution.

Seeing these disparities reminded him of a speaker who visited his college class and pointed out the unintended negative consequences of local environmental advocacy.

“He was basically calling out the group that I actually worked for. He was like, ‘This is an injustice,’” Naujoks said. “White environmental groups decided what to do to the environment without consideration to these Black communities who were suffering terribly.”

Rhodes emphasized the importance of centering the experiences of people directly affected by environmental injustice. She said that the best thing governments can do is listen to residents and be concerned about constituents.

“The only way you can address anything going on in your community or your city is by having a bond with your neighbors,” Rhodes said. “If you’re just outside looking in and you want to make change, that’s not going to work.”

The importance of centering the most impacted voices has been obvious in his legal advocacy for residents of Prince George’s County, Maryland, a predominantly Black community, Naujoks said. The county has sometimes been referred to as D.C.’s “Ward 9” because many of its residents moved there after experiencing displacement from gentrification in D.C.

Prince George’s County has experienced issues with coal ash contamination from a 140-acre pit in Brandywine, located in the southernmost part of the county. The coal ash has begun to seep into the community’s water, introducing pollutants like arsenic, selenium, boron, and cadmium. In Prince George’s County, this pollution has become so severe that the river has been subject to repeated fish consumption advisories, and several fisheries have been shut down.

Naujoks said that being in the country’s capital has not guaranteed effective local environmental policy.

“They [the EPA] keep denying giving us money to work on this,” Naujoks said, referring to the coal ash contamination. “Just because we’re right here near the nation’s capital, don’t pretend there aren’t environmental justice issues right here.”

Despite obstacles, Bartley said that grassroots activism and nonprofit organizations have been effective in prompting national conversations about environmental justice.

“We wouldn’t be talking about this topic were it not for decades and decades of activism by people in communities that were facing serious environmental hazards,” Bartley said. “That’s just a testament to the ability of activist campaigns to put this issue on the agenda.”

To help create more equitable policy, Bartley said that activists have been working to force policymakers to address environmental injustice.

“Environmental justice activists, I think, have been pretty effective at interfacing with policymakers and trying to get policy change, not just at the national level, but at local and state levels too,” Bartley said.

Both Naujoks and Rhodes have worked in different ways to hold culpable organizations and the government accountable for actions that perpetuate environmental injustice and disproportionately affect people of color in and around D.C.

Naujoks focuses on legal advocacy, suing major corporations involved in inequitable policies to encourage change. Recently, his efforts have paid off, settling a case against MetCom to halt their illegal sewage dumping into the Potomac River, with half of their $250,000 settlement going to a restoration project to bring oysters back into the river.

Rhodes, on the other hand, has utilized the power of her community and grassroots organizing to advocate for change. In her work with Empower D.C., she runs community meetings and spends time discussing the problems in her neighborhood with residents, as well as exploring potential joint solutions between the communities and lawmakers. She frequently holds marches and protests with Empower D.C. and other organizations to show they are still fighting for change.

Despite these efforts and relative progress, Bartley said, enforcement of environmental regulations has been weak.

“Supreme Court decisions have weakened the regulatory authority of the EPA, for instance, that maybe put some of the potential gains of policy change in a different light, at least, or put them into question,” Bartley said.

A Supreme Court ruling this year blocked the EPA’s “Good Neighbor” air pollution rule requiring states to reduce emissions that could impact other states. Bartley worried that this could undermine the progress that advocacy work has achieved so far.

Nonetheless, activists’ work is far from complete, in the DMV and beyond. In Ivy City, Rhodes mentioned frequent illegal dumping, or the unlawful disposal of waste like sofas, mattresses, and other household goods. In Prince George’s County, Naujoks pointed to continued soil and groundwater pollution from petroleum at the Andrews Air Force Base in Piscataway Creek.

The fight for environmental justice is a collaborative effort, and organizations like the Potomac Riverkeeper Network and Empower D.C. cannot do it alone, Rhodes said.

“We need everyone’s voices, especially when it comes to environmental justice,” Rhodes said. “We need everyone to be strong and stand in solidarity with our communities.”

Naujoks encouraged students to get involved, starting by raising awareness and learning about the intersectionality within environmental justice.

There are many opportunities for Georgetown students to get involved in environmental work, whether through academics or advocacy, according to Bartley. One such academic avenue is the Earth Commons Institute, which offers three degrees, including the newly formed B.S. in Environment & Sustainability, and the minor in Environment and Sustainability. Georgetown is also home to numerous on-campus student groups with focus on environmental justice and sustainability.

“I would just encourage especially our students to utilize the opportunities at Georgetown, or any other institutions and programs where they can get engaged, to find out the scientific foundations, the scientific basis for these prominent environmental issues,” Song Gao, a Georgetown chemistry professor, said.

While she’s hopeful that advocacy efforts will bring change to D.C., Rhodes said it’s disappointing that the District has lagged behind on environmental reforms.

“D.C. is the nation’s capital. The nation’s capital is supposed to be an example for the rest of the country. No community in the District should experience any kind of environmental injustice or racism,” Rhodes said.

“If we’re not being an example and some of our communities are suffering at the hands of the District’s neglect, then something needs to be done.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to clarify the number of degrees offered in the Earth Commons Institute.