Don’t just read the books, read the room.

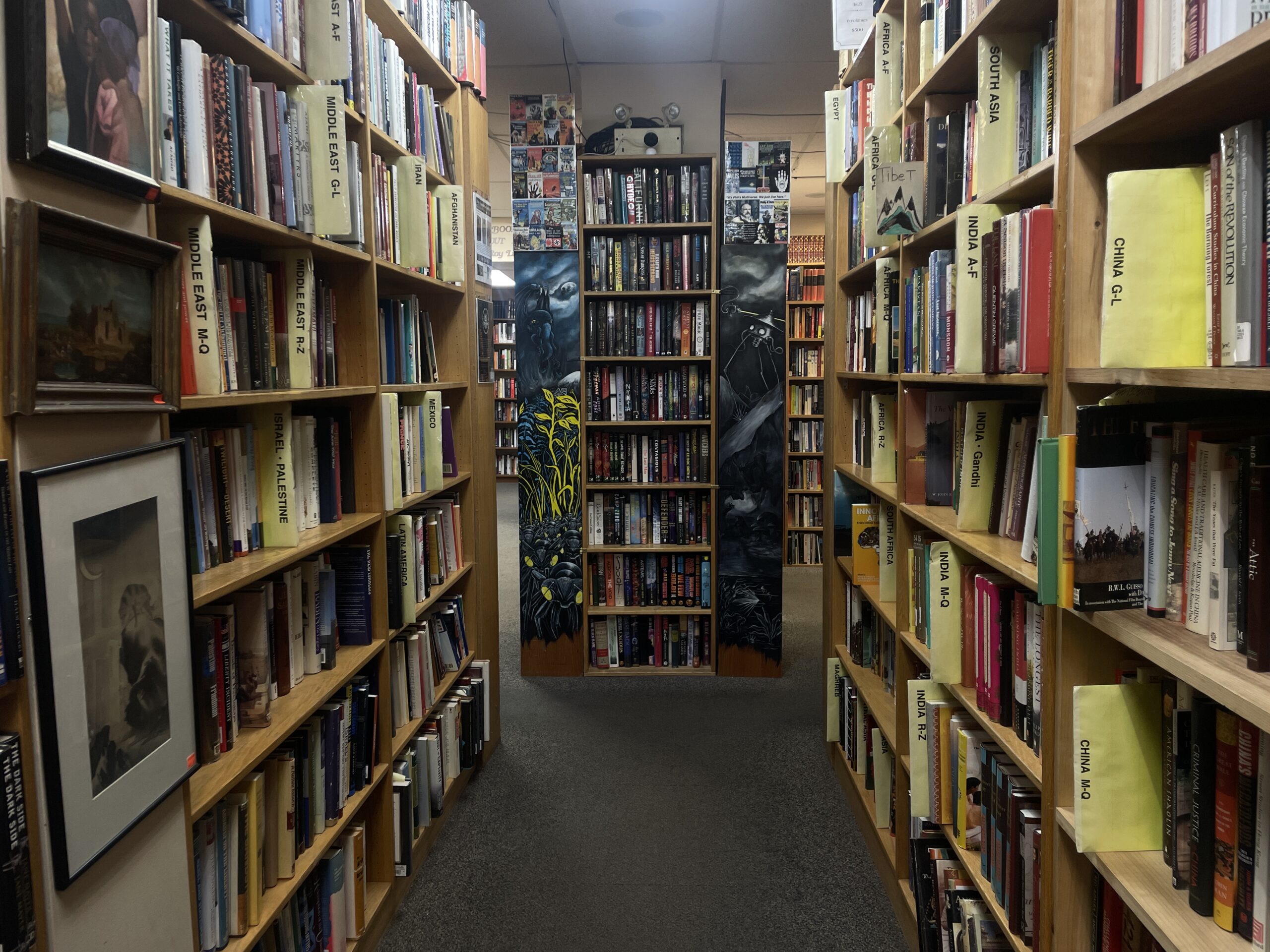

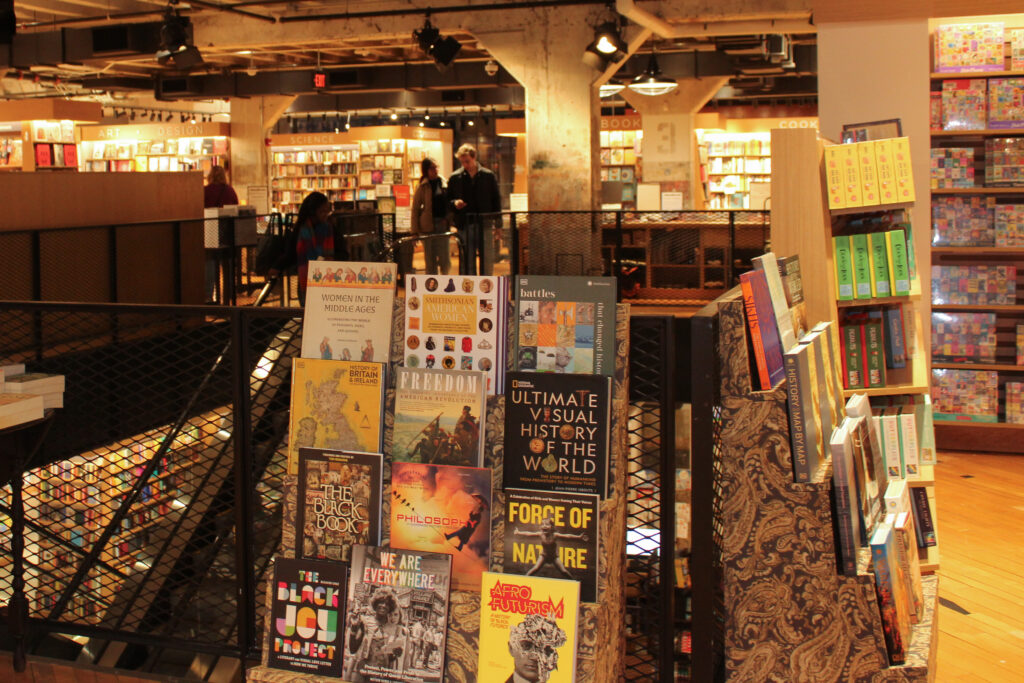

Bookshelves built from scratch, mini-mural on the pillars, and framed paintings that line the walls are among the visual charms of Second Story Books in Dupont Circle.

The art—which is also for sale—is a tribute to Second Story’s owner, Alan Stipeck, who loves old paintings and has been running the store since its founding 50 years ago.

The walls tell a similar story at Bridge Street Books in Georgetown. The previous owner was a baseball fan, and photos and artwork of Virginia’s Chesterfield Nationals still decorate the staircase walls.

If customers look closely at the walls and curated collections, they will see how indie bookstores tell the history of their owners, neighborhoods, and community in D.C.

Second Story Books and Bridge Street Books are just a few of the independent bookstores in D.C. that have weathered change in the bookstore industry—within the District and nationally—and bring local personality to D.C.’s book scene.

Books line the shelves with countless stories from afar, but the shops themselves chronicle the lives and interests of people who flow in and out of the store each day.

Photo by Sophie St Amand The Lantern Bookshop on P Street.Photo by Sophie St Amand

When customers step inside The Lantern Bookshop in Georgetown, the room is full of the chatter of people browsing the store, not entirely sure what title they are looking for.

“People sometimes ask what books we have in stock,” Susan Nerlinger, who has been volunteering at The Lantern for over 10 years, said. “And I have to tell them, ‘We don’t know what we have.’ We don’t have a computerized inventory system.”

As a non-profit run entirely by volunteers, The Lantern stocks its shelves with donated books. Nerlinger said that the donations, despite making it impossible to keep track of inventory, are a joy of volunteering at The Lantern.

A donation can serve as a time capsule of a Georgetown resident’s life—Nerlinger said that many people living in Georgetown have large collections of books and often pass them on as they age and begin to downsize their belongings.

“We’re very connected to the community of Georgetown because residents of Georgetown know about us,” Nerlinger said. “And they bring their stuff to us.”

Nerlinger pointed out The Lantern’s large collection of books about the history of Russia as an example, which she said came from donors who were academics or working for the State Department with a focus on Russia. Georgetown residents’ interests mix on the shelves, which are decorated with rare books and first editions.

Photo by Sophie St Amand The Lantern Bookshop on P Street.Photo by Sophie St Amand

Donations also allow the shop to sell a more eclectic collection of books.

“You won’t find them in a commercial bookstore, which is going to choose the books it sells based on what is optimal to sell,” Nerlinger said. “We don’t do that. We stock what we get.”

Serving the public is at the heart of The Lantern’s mission. The bookshop repurposes books for Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, and donates to the university to help students afford to pursue unpaid internships. A Bryn Mawr graduate founded the shop and many of the volunteers, like Susan, are Bryn Mawr alumni.

Beyond donations, Nerlinger also hopes that The Lantern offers a meaningful space for the local community.

“We offer a valuable public service because [The Lantern] is a place where people can get rid of their books and find new ones,” Nerlinger said. “You may not find exactly the book that you’re looking for, but you’ll have a wonderful time, and you’ll undoubtedly find something that appeals to you.”

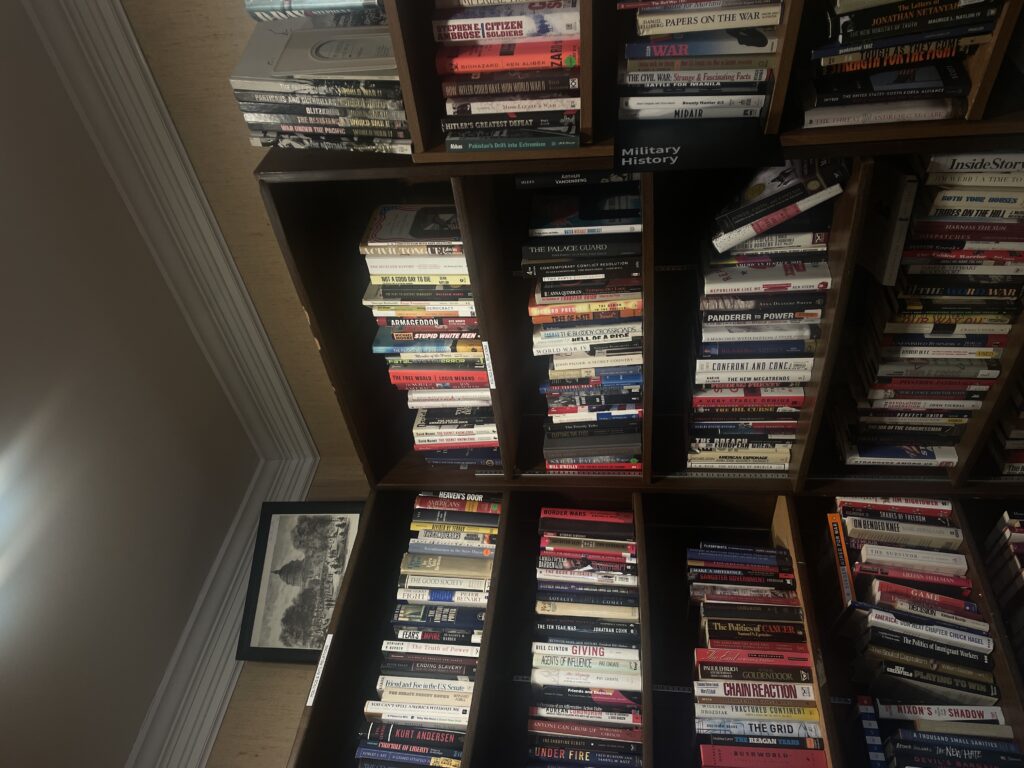

Stores that sell new books can also reflect D.C.’s local history. Rod Smith, the manager of Bridge Street Books on Pennsylvania Ave., told the Voice that indie bookstores offer unique contributions to the bookstore scene.

“Bridge Street Books is a repository of Georgetown’s knowledge,” Smith said. “We reflect the interests and tastes of people and have an effect on their interests and tastes.”

Bridge Street Books puts extra care into its poetry section, where customers pull up chairs to sit and peruse through the collection. Smith writes poetry himself, and the store hosts poetry readings that are open to the public.

While Bridge Street Books has built a close relationship with Georgetown’s readers, the customer scene may change due to Barnes & Noble’s return to M Street this fall—just a few blocks down from Bridge Street Books. Barnes & Noble closed in 2011 and has reopened in the same building.

“Barnes & Noble could open anywhere,” Smith said. “Yet they open near independent bookstores.”

The new Barnes & Noble did not respond to the Voice’s interview requests for this piece.

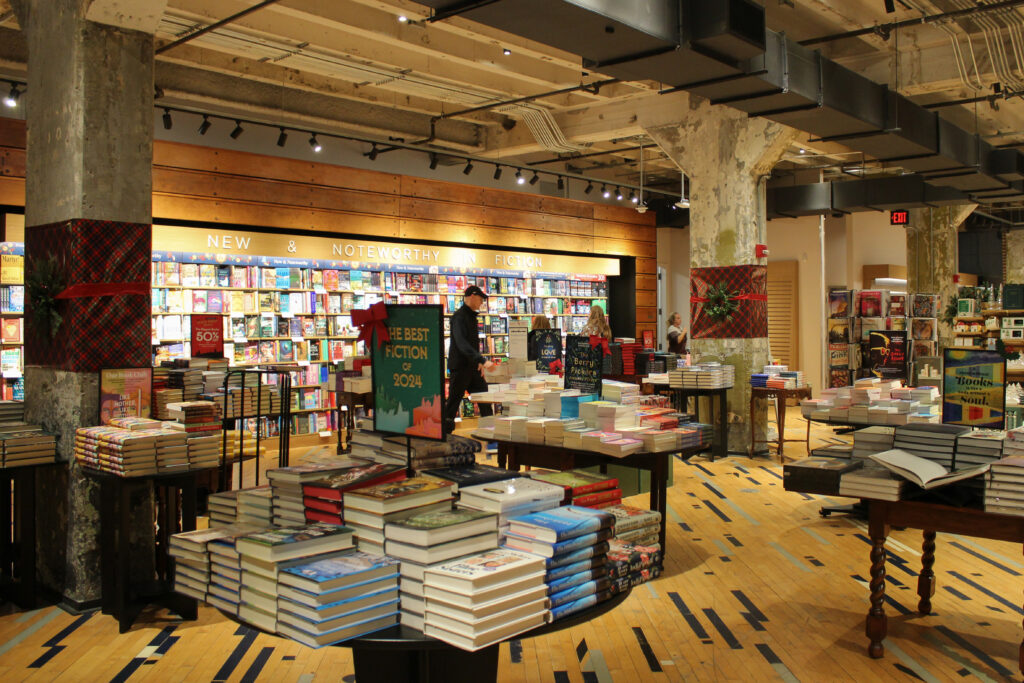

Photo by Sophia Frank The new Barnes & Noble in Georgetown.Photo by Sophia Frank

While Barnes & Noble’s opening might worry some indie bookstore lovers, Politics & Prose Bookstore co-owner Bradley Graham has a slightly different take: he finds that online sellers like Amazon pose a larger threat to independent bookstores than big-name physical bookshops do.

Graham said that in the 2010s, it looked like even Barnes & Noble could go out of business as more customers shopped online, which had worried him and other bookstore owners.

“It would have been such a dramatic loss for the bookselling businesses that it would have called into question the whole idea of physical bookstores,” Graham said. “[Barnes & Noble] has been seen generally as a positive thing. The main competition remains Amazon, but Barnes & Noble is now opening more stores.”

Photo by Photo by Sophia Frank The new Barnes & Noble in Georgetown.Photo by Photo by Sophia Frank

As Barnes & Noble opens more locations—especially in larger cities—Graham said that worry about their effects on indie bookstores has complicated his feelings about Barnes & Noble’s success.

“It’s a puzzling thing to me, but also a reassuring sign that they’re coming back to Washington D.C. as a vote of business confidence,” Graham said.

In recent years, despite worries about companies like Amazon and Barnes & Nobles, an increase in indie bookstores opening in D.C. and around the country has energized owners like Smith and Graham. Smith said that the personal touch of an independently-owned bookshop is a draw for many customers.

“There was an early Amazon splash, but people are realizing that they want to buy a book from somebody that they know,” Smith said.

Graham feels that the success of indie bookstores illustrates how people value these shops’ ability to reflect the community around them.

Politics and Prose, which has three locations around D.C., is engaged with readers in the District and authors around the country, hosting event programs and book tours for anyone to attend, free of cost. It also offers writing classes online and in-person and provides self-publishing services for independent authors like editing manuscripts and designing covers.

The company also recently sponsored an event at The Anthem with Angela Merkel and Barack Obama, which sold out all 3,200 seats.

While Politics & Prose is well-loved for its community events, Graham acknowledged the challenges of running an indie bookstore.

“There’s got to be something to what we do that explains the endurance of independent bookstores,” Graham said. “Still, we have to recognize we’re still many fewer than we were 20 to 30 years ago. And it’s still a tough business.”

Photo by Sophie St Amand Politics & Prose on Connecticut Ave. NW in Chevy Chase.Photo by Sophie St Amand

In the face of these challenges, Grace Gretschel, who works at Second Story Books, encouraged people to shop indie or secondhand when possible. However, they acknowledge that independent bookstores are not an option for everyone. Gretschel has found that indie bookstores are often easier to come by in urban, expensive areas.

“I try not to judge people for shopping at chains,” Gretschel said. “I know independent bookstores aren’t always accessible.”

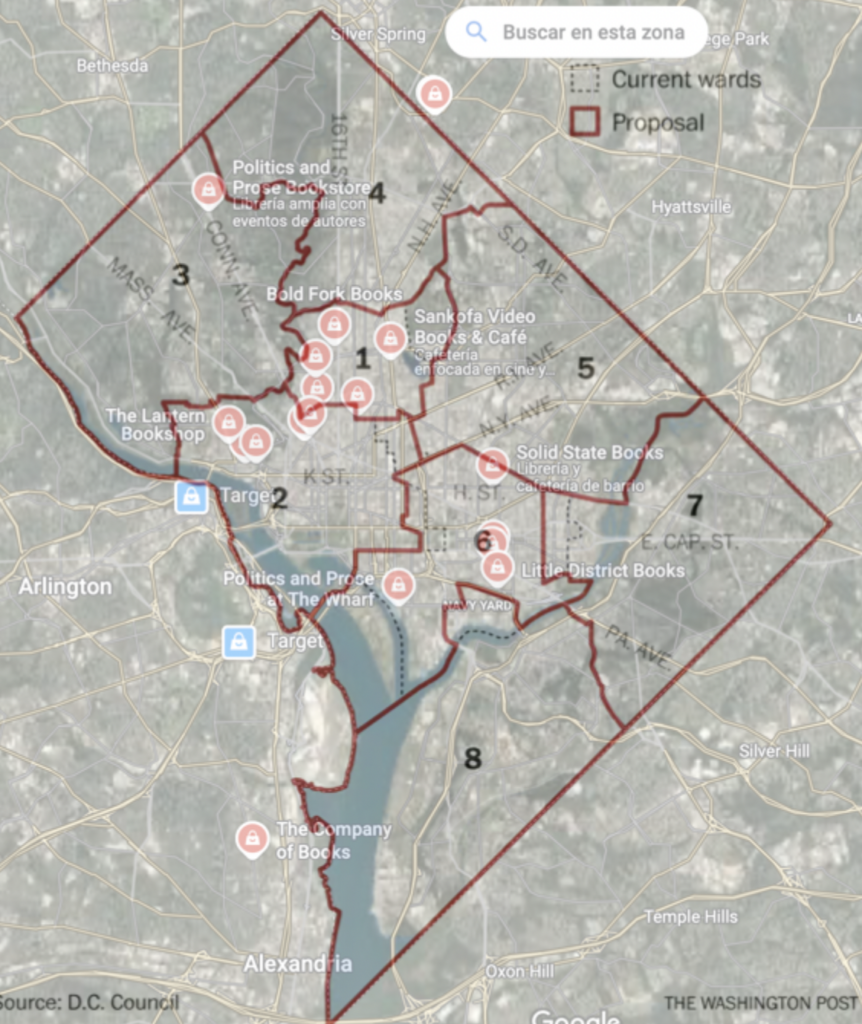

Map credit to Google Maps; Ward map credit to the Washington Post & D.C. Office of Planning. Overlay by Sophie St Amand A map of Google Maps’ recommended independent bookstores in D.C. with an overlay of the 2022 D.C. Ward Map.Map credit to Google Maps; Ward map credit to the Washington Post & D.C. Office of Planning. Overlay by Sophie St Amand

D.C. has high concentrations of indie bookstores in Dupont Circle and Georgetown, which are both in Ward 2. Wards 1 and 6 have several indie bookstores as well. The median income in each of these wards is about $100,000, compared to about $71,000 in D.C. overall.

The Voice could not find record of any indie bookstores in D.C.’s Wards 7 and 8. The median household income in Wards 7 and 8 is about a third of that of Ward 3, the richest ward in D.C. These disparities date back to 20th century laws that fueled racial segregation, gentrification, and displacement in D.C.—issues that continue in the District today.

Graham said that one reason he thinks Politics & Prose survived massive closings of indie bookstores in the 2010s was because of the store’s location in Chevy Chase, D.C., which has one of the highest literacy rates in the country.

In that sense, indie bookstores’ reflect more than the literature that people in the area enjoy. Areas with different concentrations of independent bookstores might give further insight into the persistence of injustice in D.C., such as income inequality as well as disparate access to resources that raise literacy rates.

Gretschel said that readers who have the opportunity to shop at independent bookstores should use that opportunity to support their local businesses when searching for a new read. They added that readers may find books there that are more catered to their interests than they expected.

“[Second Story] is selective with the books that we accept and we have a collection of rare books that D.C. has welcomed as part of the book scene,” Gretschel said. “Even if you don’t get anything, it’s a cool store to look around and just stare at.”

Graham added that indie bookstores also have the advantage of knowing their audience, giving them a local charm.

“We try to reflect the neighborhoods that we’re in by knowing our history and knowing the customers individually,” Graham says. “It’s gratifying to connect them with books they might not even know they might like.”

Photo by Sophie St Amand Second Story Books in Dupont Circle.Photo by Sophie St Amand