One weekend when I went home, toward the beginning of the semester, my brother had a tantrum. He was showing me his new toy, earned at school after a week of hard work, when he realized a piece of it was missing. Tears ensued, followed by wails of agony, and he threw himself into a self-destructive spiral of violence and hysteria. In response, I tore the living room apart as if that missing piece meant life or death. I pulled out couch cushions and yanked open drawers while trying to offer solutions to my brother, who sobbed and shrieked in an armchair. He dragged his nails down his arms and kicked at no one in particular. My mom, exhausted, looked at me. “Did you miss this?” she asked. Though I knew she was being sarcastic, there was a part of me that wanted to respond: yes.

My brother was diagnosed with autism as a toddler when I was seven. From that moment on, I embraced my role as his older sister. I translated his ever-changing thoughts and emotions when he couldn’t articulate them. I knew the right thing to say that would ease his constant sobs. Our relationship made me who I am. Although he’s a teenager now—more brash, more annoyed, and more anxious—he has always been the most influential person in my life.

Coming into university, I expected many emotions: the excitement of living alone, the anxiety of meeting completely new people, and the stress of adjusting to a new lifestyle. But grieving my brother’s presence and my role as his big sister was something I never expected.

Up until I started Georgetown, everyone I was around knew my brother was a part of me. In high school, my classmates and teachers would ask me about his school and my therapists were always updated on his antics. If they saw scratches on my hands, they knew the night before was difficult. Both of my summer jobs were through therapy programs he was in. When his aggression prevented him from going to dinner parties with family friends, I felt useless without having someone to care for throughout the evening. He was Max, I was Ruby. Yes, he could be frustrating or irritating, but my existence was irrelevant without him.

But at Georgetown, everything was different. There was no one to ask how he was, and even if there was, I wouldn’t have the same stories, because I’m not there anymore. On the off chance I did have an anecdote or two, people responded with confusion or awkward laughs. “He must be really little then?” No, he’s fourteen. “Why would he do that?” He’s trying his best. “Are your parents okay?” They’re used to it.

My friends at Georgetown hadn’t seen the evenings I spent hugging and rocking his anxiety-ridden body. Nor did they see our post-therapy Chick-fil-A runs, us square-dancing in the living room, or reciting lines from Despicable Me 2 till he laughed and stimmed with joy.

They saw me as I was away from home, which was really starting to feel like someone I wasn’t at all. I couldn’t be myself without being known as my brother’s sister. I felt further separated from myself by the fact that I didn’t have him to watch out for and at times, fret over, at Georgetown. Despite living only thirty minutes away, our lives seemed to be so removed from each other. Because of his behavior, he has never visited campus. He tells me his problems over the phone and in essay-worthy emails. “Apa,” he calls me, the Urdu word for elder sister. “I got into an argument with Baba.” I try to be the same, sometimes understanding, sometimes admonishing sister I was at home, but something is different. I’m not a part of his life anymore: I’m a bystander watching it unfold.

I thought I lost myself on campus. Somewhere between home and the Hilltop, I had slipped away. But slowly, I began to realize that separation allowed me to truly find myself. At home, my mind was occupied with my brother. As strange as it sounds, I never really considered I was a complete person without caring for my brother’s needs. I spent so much time worrying over him that I never truly realized myself.

It hit me when a friend told me I seemed that I could be an only child, or perhaps a youngest. Everyone agreed. This was unfathomable. My entire existence had been being an older sibling. My identity revolved around my brother. Was I a bad sister for leading people to believe otherwise? Was I so neglectful of him that people couldn’t conceive of me having someone like him in my life? I called my mom, asking for answers. To comfort me, she told me that every time she saw a sibling meme reel on Instagram, the eldest one reminded her of me. This wasn’t enough. I didn’t want to seem like an older sibling just to her, I wanted to be seen as an older sibling to everyone at Georgetown as well.

But there was no way to force a perception of me onto someone else. “It’s not a bad thing,” people told me. “It’s just who you are.” I wondered if they were right. Perhaps not in the way they implied, but in the way that it wasn’t a bad thing to be known as an individual outside of my brother. Who I was didn’t have to be who I was in relation to someone else.

There was a small part of me that relished in not having the weight of the responsibility of being his sister at Georgetown. When someone asked me how I was, I could respond as how I was, without recalling the stress of the previous night or his most recent antic. Being labelled as something other than a big sister inflated that. Up until this point, I felt guilty for even considering that being his sister was not the fullest version of me.

I confessed this to a friend one night in Leo’s. “You aren’t limited to one role, Raha,” she told me. “Who you are here is not the same as who you are at home and it will never be. You can exist in all those places at once and you are still you.” I stared at her, knowing she never had to ask me about a post-tantrum scratch on my arm. I held the bowl I knew he’d never eaten from, I sat in a chair I knew he’d never touched, I felt the warmth of the lights I knew he’d never sat under, and I had nothing to say but “yes” because she was telling the truth. The emptiness I felt was because I never let myself think I could be someone more than my brother’s sister. But here I was, in a place where I could be anything but a sister. And that saved me, because it gave me something more to be than a person for someone else. I could be a person for me.

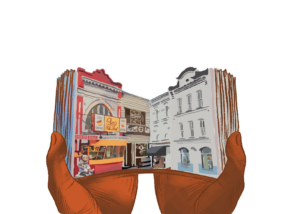

Being away from my home, I’ve been forced to see and understand myself without having someone else to put first. Relatives told me it would be good for me to live without the self-imposed responsibility of him. I didn’t believe them until now. I need to be away from him to learn that I was a whole person on my own. When he was around, I could never fully relax because I felt I was responsible for him. At Georgetown, I’m only responsible for myself. He was a big part of my childhood, but there’s so much of me that exists outside of him. There are movies I love that he refuses to watch and music I listen to that he can’t stand. Art isn’t his favorite, but I love paint. I paint buildings and trees, but I mostly like to paint for other people. I think people are incredible and I usually have a hundred questions to ask, which he would hate to answer. I’ve found that my favorite topic of conversation is families, which could be just because I love my family so much and I want to hear about someone else’s love. But even though that is outside of him, I’m still a good sister.

A big part of the transition from high school to college, forgotten by the NSO packets and countless presentations, is finding who you are in a new place with new people. Understanding the dual identities of who I was at home and who I am at the Hilltop made me a fuller version of myself. And though I still miss seeing my brother every day, he is a part of me that I will take with me wherever I go.