On the first weekend of the lunar calendar, visitors gathered at a church near D.C.’s Chinatown to celebrate Lunar New Year, enjoying a lion dance performance as volunteers dished out noodles and dumplings. But beneath the lanterns, streamers, and joyful glow of the holiday festivities, the event carried a heavier purpose: organizing against gentrification in Chinatown.

Photo by Katie Doran The Hung Ci Lion Dance Troupe performs a lion dance at the Metropolitan Community Church at the Feb 1. town hall.Photo by Katie Doran

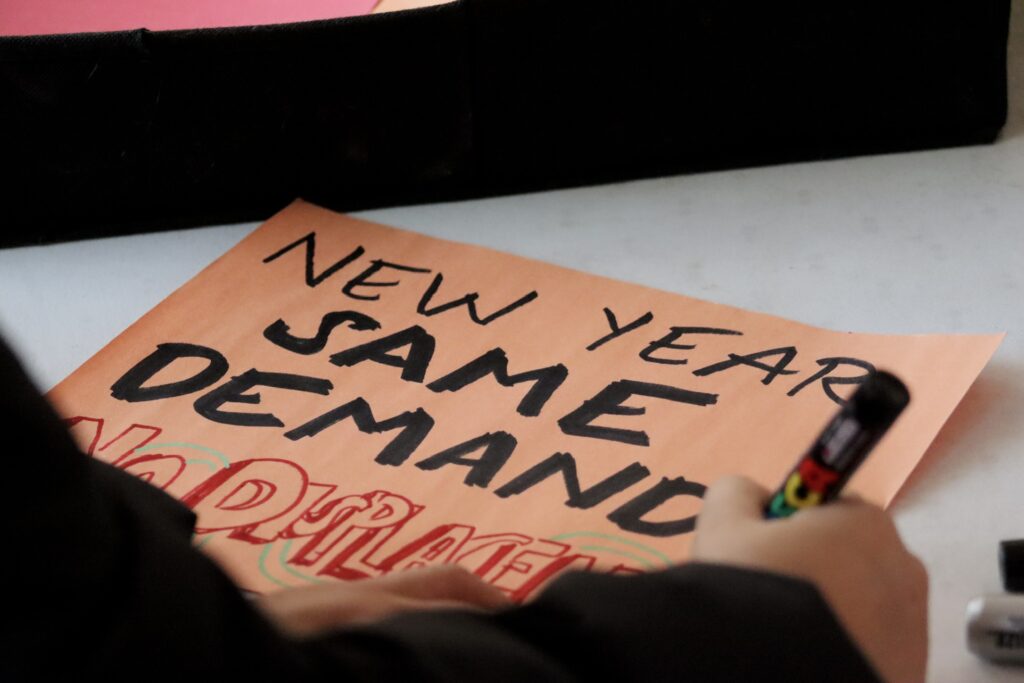

This Feb. 1 town hall was organized by Save Chinatown Solidarity Network DC and hosted at the Metropolitan Community Church. Attendees listened to activists and Chinatown residents speak about displacement and their hopes for the neighborhood’s future. Afterward, attendees colored posters to be carried at D.C.’s annual Lunar New Year parade that read, “New year same demands” and “Residents must drive community decisions.”

Photo by Katie Doran An attendee of the Feb 1. town hall works on a poster.Photo by Katie Doran

The town hall was one small part of a yearslong, concerted effort to combat displacement in D.C.’s struggling Chinatown as the District government moves forward with plans to “revitalize” the neighborhood, which locals worry will only worsen gentrification.

Chinatown’s community

D.C.’s Chinatown—spanning just a few blocks along H and I Streets Northwest—has never been huge in area or population. But in recent years, it’s only become smaller.

In 2010, there were about 3,000 Chinese residents living in Chinatown, but the 2020 census showed just 361—a nearly 90% decrease in just one decade. In recent years, Chinatown has also seen closures of businesses, restaurants, and stores that served as Chinese cultural hubs.

Despite these changes, activists emphasized that Chinatown still has a strong community fighting to preserve their home.

“We hear a lot about D.C. Chinatown being bad, being dead, and being really embarrassing in comparison to New York and Philly. I totally feel that sentiment 100 percent, but at the same time, there are still residents living there, and there are still small businesses operating there,” Cassie He, an organizer with Save Chinatown, said. “Chinatown isn’t dead.”

He encouraged D.C. residents across the city to work to protect the remaining community in Chinatown.

“If we’re able to shift our mindset to think, there’s actually a really long history of activism and organizing in Chinatown. There are two tenants’ associations that are so incredible,” He said. “There are small businesses that are vibrant. This is a community that is still alive, and we should still be fighting for them.”

For activists like He, part of fighting for Chinatown means pushing for investment that focuses on current residents’ needs, preserves existing businesses, and fosters growth for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) owned small businesses.

D.C.’s plans to build “something new”

The local government, however, has a different vision for the neighborhood.

Last May, the Gallery Place/Chinatown Task Force unveiled “8 Big Ideas” for revitalizing 130 blocks of Downtown D.C., including Chinatown. The plan aims to bring 16,500 new residents to the area by transforming the space around Capital One Arena, installing more greenspace, building more residential units, and organizing more street life events, among other proposals.

Save Chinatown pushed back on these ideas, unveiling their own plan of seven “Bigger Ideas” for Chinatown at the Feb. 1 town hall. Activists and residents spoke about each of these points, including building affordable housing, investing in AAPI-owned small businesses, decreasing policing to shift focus to other community resources, and prioritizing current residents’ involvement in neighborhood decision-making.

Shani Shih, a founding member of Save Chinatown and a lead organizer in the group’s steering committee, said that the city’s plans for Chinatown show a lack of care for residents’ wishes.

“A lot of their plans for developing this neighborhood involve coming down and creating something new to transform, to revitalize, without any deep understanding or engagement with what exists and how important what this existing community is to the character and the heart of what Chinatown is,” Shih said.

Many of the District’s plans for Chinatown do involve building “something new.” The “8 Big Ideas” came on the heels of the “Downtown Action Plan,” a $400 million five-year plan to revitalize Downtown D.C. that Mayor Muriel Bowser announced in February 2024. The plan includes tens of millions of dollars in investments in retail, parks, office buildings, policing, arts and culture, residential space, and more.

“We have a plan to reposition the city better than ever before. With key investments from our partners, we’ll be able to create safer streets, support new and existing businesses, welcome new residents, and offer a vibrant 24/7 community that attracts everyone to our district,” Gerren Price, president and CEO of the DowntownDC Business Improvement District (BID), which helped design the plan, said in a press release.

The Downtown Action Plan suggests various projects and investments in Chinatown, but another controversial plan focuses on just one investment in the neighborhood: Capital One Arena.

In December, the D.C. Council approved the Downtown Arena Revitalization Act, a $515 million agreement for the city to purchase and renovate Capital One Arena, located in the heart of Chinatown. In exchange, Monumental Sports & Entertainment, which currently owns the arena as well as the Washington Capitals and Wizards, will have the two sports teams play in the city until 2050, following threats of moving the teams to Northern Virginia.

“We are going to have a state-of-the-art urban arena in Downtown DC and that’s a great deal for DC, for the teams, and for the fans,” Bowser said in a March 2024 statement when the deal was first proposed. “This is a win-win for our city and the teams. This is a catalytic investment in Downtown DC.”

The Downtown Action Plan and the Downtown Arena Expansion Revitalization Act would have the city pour almost a billion dollars into development in Chinatown over the next few years. Activists worry that the influx of money will further gentrify the area, continuing the displacement of the neighborhood’s current residents. Save Chinatown described these plans, combined with the “8 Big Ideas,” as a “death sentence for what remains of Chinatown.”

The DowntownDC BID and the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning & Economic Development did not respond to requests for comment from the Voice, but local government officials have maintained that their plans for Chinatown are in the best interest of current residents as well as potential future residents, tourists, or visitors.

“It is critical to the success of our city that we focus resources and conscientious attention to preserve, protect, and build Chinatown in supporting the residents and Chinese-owned and focused businesses who are there now and ensure our tourism efforts are inclusive and a draw for visitors from around the world,” Ward 2 Councilmember Brooke Pinto wrote in a statement to the Voice.

Ongoing displacement

Activists say that gentrification in Chinatown is growing even before the city’s new plans kick into gear. For example, in a controversial move in May 2024, the D.C. Zoning Board approved plans to build a nine-story luxury hotel on H Street. The hotel would require redeveloping several row houses and would push out two small businesses, Full Kee Restaurant and Gaoya Salon.

According to He, Save Chinatown is asking the developer of the H Street hotel to enter into negotiations to create a “community benefits agreement” with Chinatown residents.

“If the hotel is to develop and demolish the existing small businesses, we are asking in exchange that they provide some type of community benefit in order to preserve the things that they’re demolishing,” He said.

Jenny Wang, manager of Gaoya Salon, spoke at the Save Chinatown town hall earlier this month about the importance of businesses and residents being able to stay in Chinatown.

“Language is the major barrier that causes Chinese-Americans to stay in Chinatown,” Wang said in a speech in Mandarin. “As Chinese people, we hope that the U.S. government and D.C. government will preserve Chinatown’s culture.”

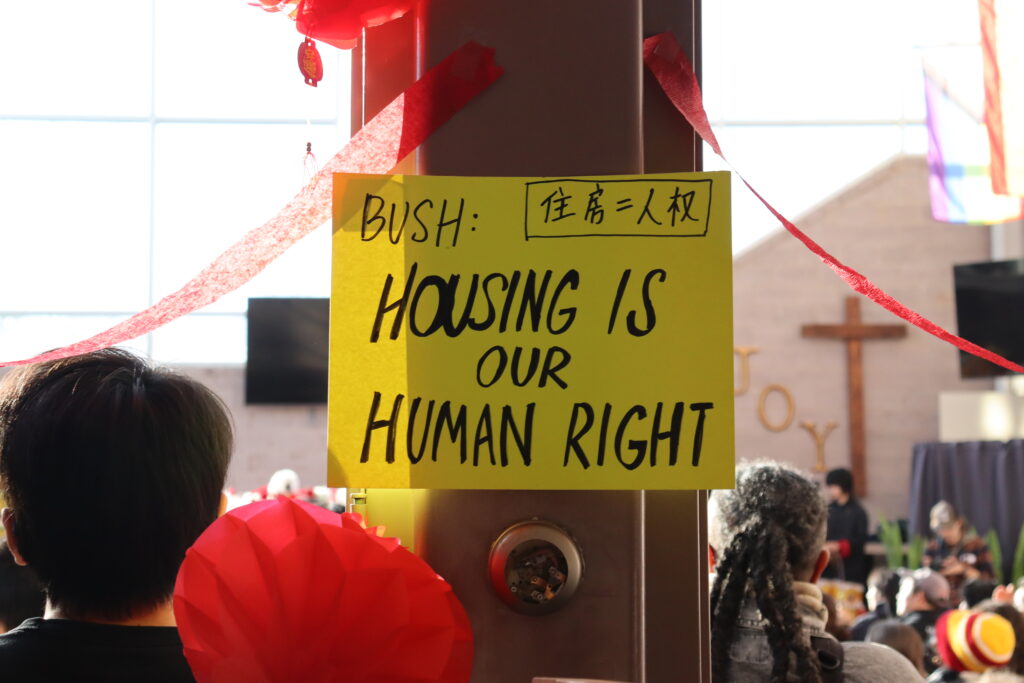

Wang is also a resident of Museum Square, one of Chinatown’s two affordable housing complexes. Museum Square is facing worsening living conditions and constant facility issues, including broken elevators that pose safety risks for the mostly elderly residents of the nine-story building.

Museum Square residents say their landlord, Bush Companies, is trying to push out tenants by refusing to address maintenance issues in the building, so the company can then redevelop the land for more profitable uses, such as market-rate condos or retail. There are now only 70 remaining residents in the 302-unit apartment complex.

Photo by Katie Doran A poster at the Feb 1. town hall addresses Bush Companies, the landlord of Museum Square.Photo by Katie Doran

Activists say the city’s focus on new retail and arena development in Chinatown is frustrating when residents are being pushed out of the already limited affordable housing in the neighborhood.

“Our demand around Museum Square is very clear, is for the city, instead of pouring billions into the redevelopment and the revitalization of Chinatown, is to divert some of these funds, which is a drop in the bucket for them, to preserve affordable housing,” Shih said.

Community-centered investments

Beyond housing, activists pointed to several other examples of possibilities for community-centered investments. Some have pushed for building a Chinese grocery store in the neighborhood, as Chinatown currently has only a small convenience store and a Safeway a few blocks away, neither of which stock many Asian grocery products. Many Chinatown residents regularly travel to Virginia to buy Asian groceries.

Chef Kevin Tien, who owns Moon Rabbit, a Vietnamese restaurant in Chinatown, spoke at the Save Chinatown town hall about his hopes for an Asian grocery store in the neighborhood, but he also emphasized the need to protect current businesses.

“It’s not just about future businesses. It’s about preservation of businesses that have been there for generations. That’s what keeps Chinatown, Chinatown,” Tien said.

Many activists express support for expanding business activity in Chinatown, but disagree with the government on how to best achieve this goal.

“We want to make it clear that we are not against increased investment in Chinatown. But the city has made absolutely no plans to invest in community alongside all of these investments they’re making to developers and new businesses,” He said. “They have said nothing about how these businesses would be Asian, Asian-owned or owned by residents, or that they would hire residents.”

Shih also said that D.C.’s government has overlooked marginalized populations while making their plans for Chinatown.

“A lot of these changes have been predicated on the silence and the exclusion of the voices of our most vulnerable and our low-income, working-class, long-term residents, Chinese, Black, long-term residents of this community,” Shih said.

As debates continue around Chinatown’s future, activists emphasized the need for collaboration across neighborhoods, inviting all D.C. residents—including Georgetown students—to show their support for Chinatown’s residents, such as by volunteering at Save Chinatown events.

“Whenever you’re living in a place, however temporary, I think it’s important to get connected to the movements that have been started before you,” Peter Atwill, a member of Save Chinatown’s steering committee, said. “There are very small things that you can do without having a huge knowledge base, supporting the activism that’s going on around you.”

Photo by Katie Doran Peter Atwill, from Save Chinatown, speaks at the Feb 1. town hall.Photo by Katie Doran

Despite the challenges facing Chinatown, Shih emphasized that the neighborhood remains a cultural center and symbol of community for both residents and other visitors, particularly immigrants.

“The history of Chinatown is the history of diversity in the city and in this country, of how immigrants work to fight to have a place in society and have a voice,” Shih said. “It’s a space where folks can find a sense of belonging, a sense of connection to culture and tradition.”