Cigarettes are back, and they are sexier than ever. They emit a mysterious aura, serving as a chic accessory for parties or study breaks outside Lau. By smoking a cigarette, one can emulate the philosophical pensiveness of Sartre or the rock ’n’ roll energy of Timothée Chalamet playing Bob Dylan. Cigarettes also embody brat (2024). As heard in the lyrics of “Mean Girls”: “with the razor-sharp tongue stuck to skinny cigarettes […] yeah she’s fucked up, but she’s still in Vogue.”

The aestheticization of cigarettes in music, film, fashion, and even academia has contributed to its persistent allure. But haven’t we already been told about a million times that cigarettes are bad for us? Cigarette packaging depicts blue and choking faces in hospital beds, mutilated and amputated limbs. Despite its killer effects (literally), cigarettes are still viewed as fashionable. Perhaps it’s because, as one friend once described to me, “smoking is like a form of cultural nihilism. Who cares about a drunk cigarette when the world is ending because of the climate disaster?” With the anxiety-producing landscape of 2025—wildfires, hurricanes, plane crashes, a constitutional crisis, artificial intelligence, COVID-19, and now measles—it seems like the world around us will get to us quicker than a nicotine addiction.

However, by adopting this nihilistic attitude with each drag of a cig, we are choosing to ignore the exploitative history and current reality of the tobacco industry. Smoking is not just a neglect of our own health, but of others’ as well.

In Cigarettes Inc.: An Intimate History of Corporate Imperialism, Nan Enstad discusses how the American Tobacco Company’s North Carolina factories racially segregated their departments in the 1930s, employing Black workers in leaf production and white workers in cigarette production. Leaf department jobs paid the least and had been associated with Black labor since slavery. Factory conditions for Black workers were hot, dirty, dusty, poorly ventilated, and lacking in sufficient toilets and sinks, while white workers had newer and cleaner facilities. The American Tobacco Company used segregation to justify pay differentials, maximizing its profits.

To further cut labor costs, British American Tobacco (BAT) expanded their production to Asia, establishing its first factories in Shanghai. In 1922, the U.S. Department of Labor expressed the belief that the Chinese laborer was “industrious, able to subsist on comparatively little, [and] possesses splendid endurance.” This racialization of Chinese workers as “industrious” and possessing “splendid endurance” justified the starvation and mistreatment of BAT factory workers, as lunch breaks and even bathroom breaks were forbidden.

Workers in Shanghai BAT factories protested their mistreatment and poor working conditions in the 1920s. When their workers went on strike, BAT factories employed the military, hiring British watchmen and guards to defend the factory compounds. Chinese authorities protested the presence of foreign military on their soil, but they were unable to stop BAT, underlining the company’s colonizing power. BAT’s defiance of local authority and use of military force to crack down on workers’ strikes shows how cigarette production and imperialism in Asia went hand-in-hand.

Though a hundred years ago, this history matters because BAT is currently worth almost 90 billion dollars and would not have been able to accumulate its wealth without this racist and imperialist exploitation.

Today, U.S. tobacco production continues to outsource labor to other countries, taking advantage of low wages and unfair labor practices. A 2010 study by Human Rights Watch revealed instances of child labor on Philip Morris International farms in Kazakhstan. The report also cited studies that show that laborers’ lungs can absorb around 36 cigarettes worth of nicotine from a day’s work in a tobacco field.

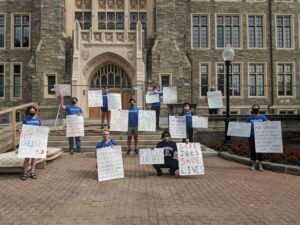

Child labor continues to be an issue on U.S. soil as well. There are thousands of children, especially those of migrant backgrounds, in Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia working in tobacco fields. Government policies exempt tobacco production from regulations that prevent child labor. The Fair Labor Standards Act does not require minors to obtain work permits for agricultural work, nor does it limit the number of working hours per day. Tobacco production tasks are also excluded from the Hazardous Occupations Order, which deems specific agricultural jobs as too dangerous for minors under 16.

In an NPR interview, José Velásquez Castellano, now a student at Tufts University, detailed working on South Carolina tobacco fields when he was 13. He described how tobacco fields had a “greenhouse effect” where temperatures rose to over 100 degrees. Nicotine seeped into his skin from contact with tobacco leaves, causing nicotine poisoning with symptoms such as dizziness, headaches, nausea, vomiting, dehydration, anorexia, and insomnia.

The aestheticization of cigarettes depends on keeping the workers who produce cigarettes out of the consumer’s view. What you don’t see in film, on television, or during drunken nights out are the humans who have toiled to produce the cigarette. By ignoring the bloody history and current reality of cigarette production, one can light up, smoke, then crush the stub on the ground without realizing the human cost of this indulgence. The disposability of cigarettes mirrors how tobacco companies treat their workers as disposable. Cigarettes are not an escape from our anxiety over the crashing and burning world—they just add to the flames.