Over the many years of Georgetown’s history, student culture has transformed from that of an all-male Catholic institution to the wider breadth of identities, cultures, and perspectives that we share on campus today. Part of this evolution has included fashion, and the ways students have chosen to express themselves.

In 1798, less than a decade after John Carroll first founded Georgetown, men were recommended to have 6 handkerchiefs and four cravats in addition to their uniform of black coats, black vests, white shirts, and black bow ties.

The uniform requirements did not end until 1968, over 150 years later, but male students had been playing with the dress code long before then.

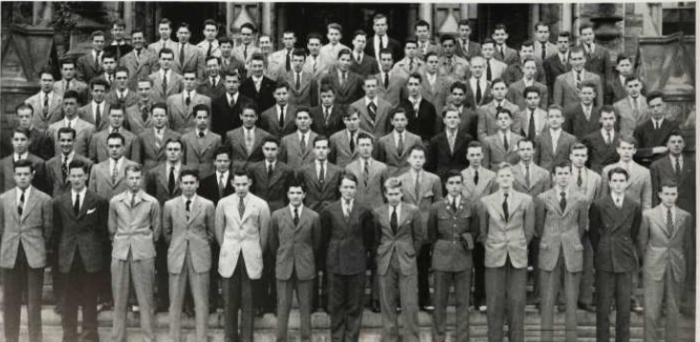

By the 1940s, the men’s traditional coat and tie had transformed into more lenient versions, with students playing with the colors of their coats or different tie patterns.

Freshman class of the 1942 edition of Ye Domesday Booke

Nevertheless, the general enforcement of neatness and kept remained: all hairstyles were uniform, kept short and gelled back at all times.

As if to mark the changing of the times, the dress code was abolished in 1968, just one year before women were allowed to enroll in the College of Arts and Sciences for the first time. Female students had been on campus for a while, as the School of Nursing had been exclusively for women, and the medical school, Walsh School of Foreign Service, and former School of Language and Linguistics had allowed women since the 1940s.

Their dress code was outlined in a guidebook for female students called “Ms. G. Goes to Georgetown,” first written in the early 20th century. The book, published by the School of Nursing, provided a comprehensive set of rules for how women should behave in their lives at Georgetown, including expectations for how they should style themselves. They had to always look “presentable” and dignified, as refinement was included in the definition of the whole person.

For these nursing students, hair had to be neat, makeup minimal, and nail polish natural, and jewelry was not permitted. “Personal pride is an inherent quality of the weaker sex,” one quote from the 1962 handbook read. The general trend among women was to wear skirts, blazers, blouses, and dresses in neutral colors, adhering to a very business professional culture.

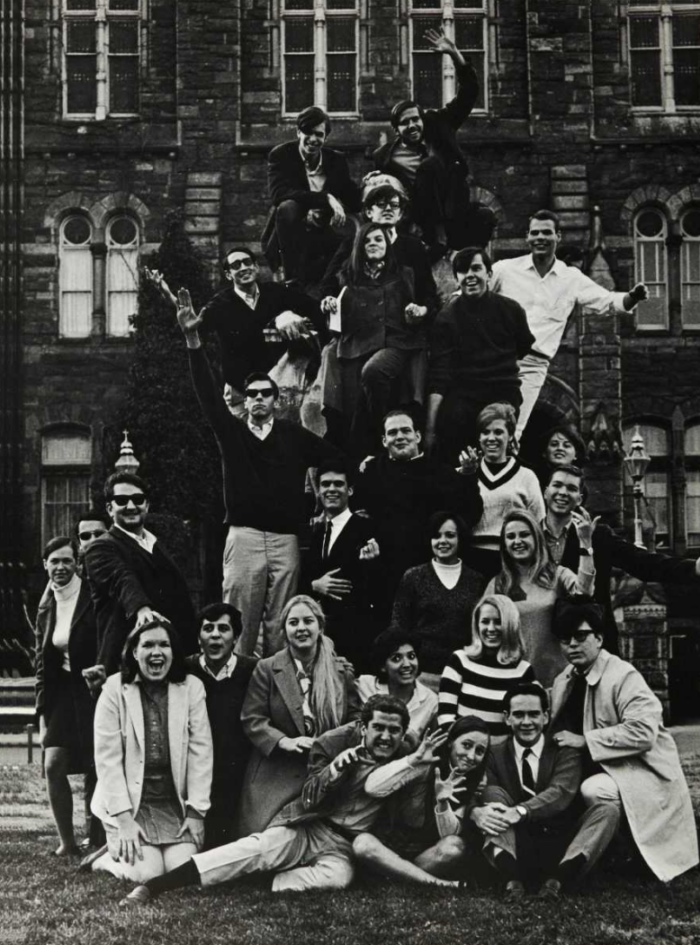

Confraternity of the Christian Doctrine club picture in 1962 edition of Ye Domesday Booke

Women were still a vast minority in the school, and maintaining their position as posh and proper ladies was considered one of their jobs on top of being a college student. This fostered a sexist nature for what women were allowed to and encouraged to wear, following the normative dress code of high-class women at the time.

With the admission of women into the College of Arts and Sciences, a new era began for the Ms. G books. Their previously rigid policies on dress code faded into fewer, more lenient guidelines. Allowing more room for interpretation began to ease up the restrictions placed on women, slowly entering a period for more freedom within the dressing policies.

In fact, by 1970, only sleeping attire was explicitly said not to be worn in public or residence hall lobbies, and in all other cases, the book advised students that “personal preferences of professors should be considered in selecting classroom attire.” While this latter rule still imposed a restriction on students’ creative expression, this was also the first year that demerits for faulty attire had been abolished, whereas in previous years 10 to 20 demerits were given out for inappropriate dress wear.

But, even after uniforms were abolished in the late ’60s, campus dress did not initially experience a major shift. The general trend remained of a certain uppityness in the Georgetown student fashion, keeping up with the previous traditions.

Mask and Bauble Club in 1968 edition of Ye Domesday Booke

Although the majority of students did continue to follow implicit standards of dress, the anti-traditionalist counterculture at the time had begun to seep into the Georgetown student body. The early 1970s editions of Ye Domesday Booke, Georgetown’s annual yearbook, featured students in all types of clothing, including women in pants, men in funky colors, and all students sporting various hairstyles. Men sported shaggy, Beatles-type hair and large sideburns, and women had hair of every length, from bobs to longer looks.

Women’s enrollment during this time had increased to 50%, and they were continually increasing the diversity of the types of clothing they sported as well. They were an integral part of campus life and were no longer dressing in pencil skirts and coats everyday.

By the 1980s, students had completely stepped out of the previous cookie cutter standards and embraced styles of every kind, regardless of gender.

Photo in opening section of 1992 edition of Ye Domesday Booke

However, the expectation for student attire to be“presentable” remained, and athletic gear, sleepwear, or leisure wear—clothing styles that are commonly found on the Georgetown campus nowadays—were rarely worn in public.

Additionally, beyond the gradual inclusion of women, campus was still very uniform, with the general student body being vastly white, straight, and wealthy, which aided in maintaining a very homogenous standard for acceptable clothing. When minority students did attend Georgetown, they were surrounded by this phenotypically unvarying student population. As such, it seems improbable that they felt truly comfortable expressing their true identity and preferences with their clothing. Rather, they most likely assimilated to the majority trends in order to “fit in” on campus.

This began to change in the 2000s as efforts to support diversity were more apparent. Students from all backgrounds were featured on the yearbook pages sporting styles of all kinds, including dyed hair, and tattoos. These trends continued into the early 2010s and shifted toward more alternative styles in later years.

Now that we’ve entered the third decade of this century, it only takes one look outside to assess today’s fashion trends. Fashion from every corner of the industry can be found on our campus; from the athletes wearing school merch to the indie baddies in their Docs and maxi skirts, there’s room for everyone to express their style as they please. There is some uniformity within certain schools, like the MSBro Patagonia preppy standard. Of course, the mainstream population remains generally white and wealthy, creating an underlying sense of what you should wear to “fit in.” Not everyone may feel comfortable nor truly accepted on campus to represent themselves and their identity property. However, those untouched pockets of true creativity and expression are still apparent, shining brightly against the seas of Aritzia bodysuits and Zara wide-leg jeans.

Despite the similarities or differences, students remain reflections of the Georgetown student population itself: a place where every type of person, or style, can belong.