When I realized the college I’d be attending was next to a beautiful river, I was ecstatic. Growing up swimming, diving, and eventually becoming a certified lifeguard, I spent every summer submerged in the lakes and rivers of Washington state. I hoped the Potomac could provide me with familiarity in a place that was otherwise new.

A few weeks into the fall semester, I began to yearn for that feeling of jumping into cold, fresh water—shocking your system awake and connecting you to your surroundings. Gazing at the Potomac from the Healey Family Student Center patio, I assumed swimming downtown was off limits, but there had to be somewhere nearby. After a quick search, I found Scott’s Run Nature Preserve, which looked perfect: a quiet trail and a natural swimming hole.

My friends and I arrived optimistic; I was ready to swim, and they were ready to see if I’d follow through. Bets were placed as we drove over but not even two steps onto the trail, we saw it: a Parks and Recreation sign with low-budget, frightening graphics and big letters reading “NO SWIMMING, BATHING, OR WADING.”

So much for that.

Ironically, our group of overachieving academics had clearly failed to do any research beyond looking at the pretty pictures. Not wanting to give up, we debated whether the fine was worth it, ultimately deciding it wasn’t. But I couldn’t stop thinking: there must be a good explanation for the rule, right?

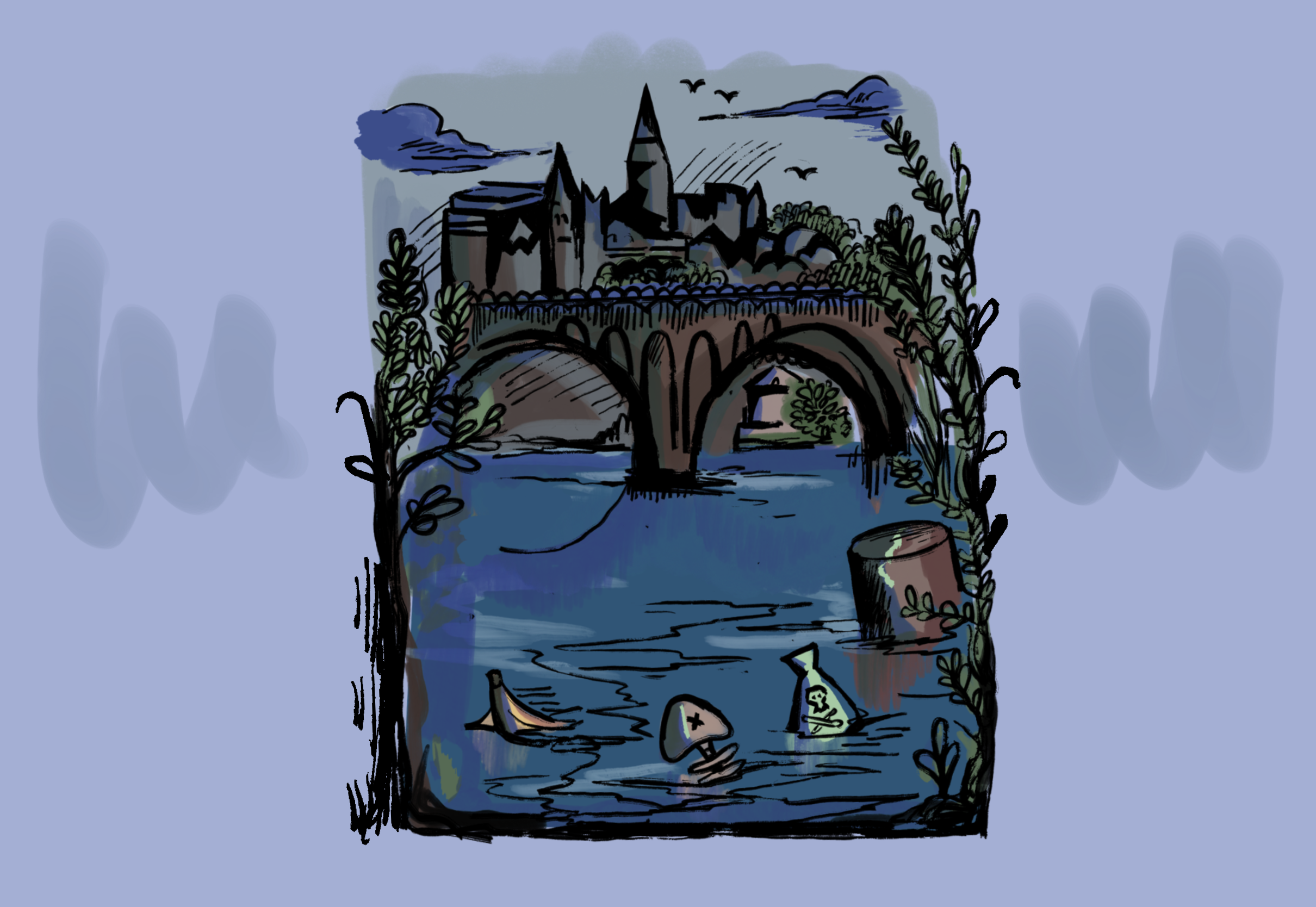

As we kept hiking, that reason became clear fast: dozens of car tires, plastic bottles, shopping carts, and other unidentifiable trash floated downstream.

Back home, the lakes and rivers were meticulously maintained. Washington state has strict water quality standards, regular testing, and aggressive cleanup programs to keep waterways swimmable. I’d spent countless summers jumping off docks without a second thought. It was just a given that the water was clean enough to swim in.

Standing there looking at the Potomac, I couldn’t understand it. This is our nation’s capital. If Washington state and even its much less relevant neighbor, Idaho, can maintain clean, swimmable waters, shouldn’t D.C.—the place where federal environmental policy is written—be doing even better?

I pulled out my phone to research. Turns out the Potomac isn’t just littered with trash—it’s contaminated. Sewage, wastewater, and agricultural runoff (think pesticides and fertilizers) from shopping centers, developments, and farms upstream flow right into it. It wasn’t just illegal to swim here. It was dangerous.

The longer we walked, the more the severity of the situation hit me. The water was still. No fish, no frogs, nothing. Just a murky, lifeless river choked by human waste. And this isn’t some forgotten industrial wasteland. This is where lawmakers debate environmental policy while the river less than a mile and a half away is too toxic to touch.

I was reminded of that hike recently when the news broke about the recent sewage spill in the Potomac. On Jan. 19, a major sewer pipe collapsed, dumping around 243 million gallons of wastewater into the river. In the following days, DC Water, the city’s utility authority, and University of Maryland researchers tested the water.

The results were horrifying.

Researchers found E. coli levels more than 10,000 times higher than what is considered safe for recreational water. They also detected staph bacteria, including MRSA, a dangerous, antibiotic-resistant pathogen that can cause serious infections via skin contact or accidental swallowing.

While DC Water later updated the report that most downstream sites met federal safety standards, “meeting standards” does not mean it is clean. It means barely acceptable for limited contact—not safe, not healthy, and certainly not swimmable.

If the river running through the nation’s capital is not clean enough for people to touch, what does that say about environmental protection for the rest of the country?

Most concerningly, the pollution isn’t distributed equally.

The Anacostia River, one of the Potomac’s largest tributaries, has been dangerously contaminated for decades. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reports that the Anacostia contains hazardous chemicals, including pesticides, heavy metals, and other pollutants that are known to disrupt the immune system, cause cancer, and alter children’s cognitive development.

The contamination is not a coincidence; it’s the product of deliberate planning and policy. Federal redlining in the 1930s designated Black and low-income neighborhoods as “hazardous,” turning them into cheap land for industrial development. D.C.’s waste transfer stations and other polluting infrastructure followed. D.C. has since sued the federal government for over a century of dumping pollutants into the river, which has disproportionately burdened these communities. A report on air pollutants found that life expectancy differs by as much as 21 years between wealthier wards and Wards 7 and 8, which are near the Anacostia. The report attributed this gap directly to an unequal concentration of pollution in these neighborhoods.

Ultimately, as frustrating as it is that we can’t swim in the Potomac, it’s unacceptable that the pollution has impacted the health and livelihood of these communities for so long.

In order to connect with our natural environment, or what I like to call going feral, we must ground ourselves with the wild, unpredictable world around us. But we can’t reconnect with nature when we’ve destroyed it. We need to hold polluters accountable, demand our policymakers increase funding for cleanup projects, and create measures that improve the health of the environment and those who most directly face its consequences.

The Potomac should be swimmable. It should be alive. And the fact that it’s not—in the capital of one of the wealthiest nations in the world—is a failure we shouldn’t and can’t tolerate.