There’s something raw about being a freshman in college. I liken my first week at Georgetown to the feeling of getting lost in a supermarket as a child, running down what feels like a mile of fluorescent aisles, each overcrowded with products yet somehow empty. I eventually found my place here, just as I eventually found my parents by the cereal. But it wasn’t as easy as calling out their names amidst produce and strangers.

As it turns out, I needed the collective vulnerability of my fellow freshmen to make myself feel comfortable in a strange and foreign terrain. I felt it in the beginning of NSO, when friendships grew out of convenience and not out of preference. Without yet belonging to a community to give us armor, we had no choice but to be friendly. I remember walking up to another freshman one night with no pretext and introducing myself with my name and my hometown (because that was all that defined us, apparently). The handshake was warm and the smile that came with it, warmer. Now, a year and a half later, we avoid eye contact. We met in a strangely comfortable vacuum where unprompted introductions were socially acceptable, if not encouraged. We no longer live in that freshman-year vacuum.

I can still close my eyes today, in the throes of my sophomore year, and recall the fleeting social transparency that got me through my homesickness. My freshman floor grew closer as the seasons changed, thanks in part to our open door policy. I could walk down the hall and know that one of my neighbors was FaceTiming with her mom or playing guitar or eating chips in bed. The type of mundane activity happening around me didn’t matter. It was the humanness I saw up close, in passing, that made my dorm feel less like housing and more like a home.

I now live in a dorm that can best be described as the hallway from The Shining, minus the twins. With each room I pass, the more suspicious I become of its inhabitants. “Sarah” and “Michael” and “Tom” all live on my floor, according to the name tags attached to their doors, but I have yet to see physical evidence of their existence, despite sharing the same space for months. “Sarah” could be a centaur taking part-time classes who also struggles to fit in the shower. “Michael” could be the first student robot. “Tom” could be my best friend. So long as their doors remain closed, I will never know.

Once a hearth, a home, carved out for my freshman floor, the common room now remains empty most nights, which is perhaps fitting for the ghosts I call my neighbors. The few times I venture in there for myself, I imagine my freshman floormates, some sprawled across the floor, playing cards, others deep in existential talks while waiting for the cookies to finish baking. These memories of last year are a deep reality, even if they are phantoms embellished in my mind.

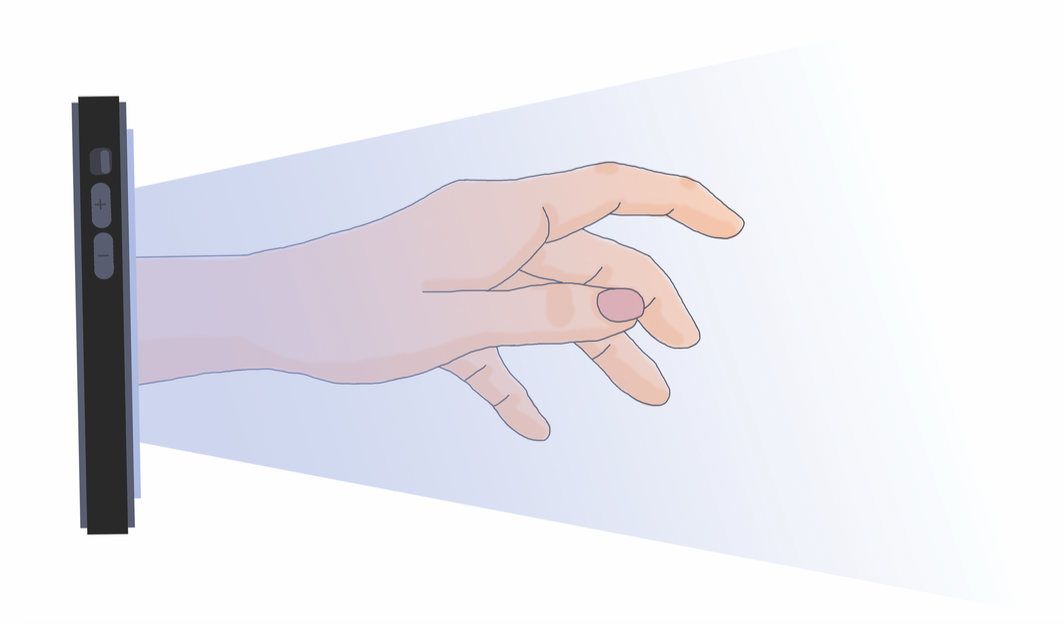

The one variable I have failed to mention up until this point is technology. Maybe the “collective vulnerability” I seek still burns within us all and it is technology that keeps it dormant. I recently rode in an elevator with a student my age and a senior citizen. For all of eight floors, the student never looked up from her phone. The senior citizen eventually took notice and asked her, “What’s the longest you’ve been away from that thing?” The student indulged him with half a smile, then returned to her phone. I narrowed my vision in on her screen, only to find her aimlessly swiping, deciding which app to click on, refreshing the Snapchat page she had just refreshed a mere moment ago, all the while never blinking. I left that elevator enraged—that the opportunity of conversation and relationships comes second to a “thing,” that we can never truly be naked. Then, I became most frustrated with myself for feeling anger when I should have felt pity. The technologies that control our lives don’t make us villains; they make us victims.

As I think back to anecdotes I heard growing up about my parents’ college days, I am beginning to piece together the mystery of my own experience at Georgetown. With no Netflix to keep them entertained on a Saturday night, they would instead leave their doors open and invite neighbors to come in. Should they be meeting a friend at the dining hall and show up early, there was no phone to keep them looking busy. And because video chat didn’t exist, they opted for in-person communication, often in the common room.

For all my bitter isolation, in the dorm and beyond, I can still find a connection with my disconnected peers. I have come to learn that vulnerability can exist from behind screens and closed doors. When I see a girl unable to look up from her phone in a space as small as an elevator, I see a girl attempting to hide. But I also see a girl lost among her own supermarket aisles that run parallel to mine.

Image Credit: Egan Barnitt

Listen to the accompanying podcast, Fresh Voices.