What is Campus Journalism?

Campus police officers have been forced to protect student newspapers at Brown University after 4,000 copies of the campus paper was stolen due to a controversial advertisement placed by conservative author and political commentator, David Horowitz. Ever since, protests have occured almost daily. Similar reactions have been aroused at schools around the country such as Duke University and University of Berkeley, California.

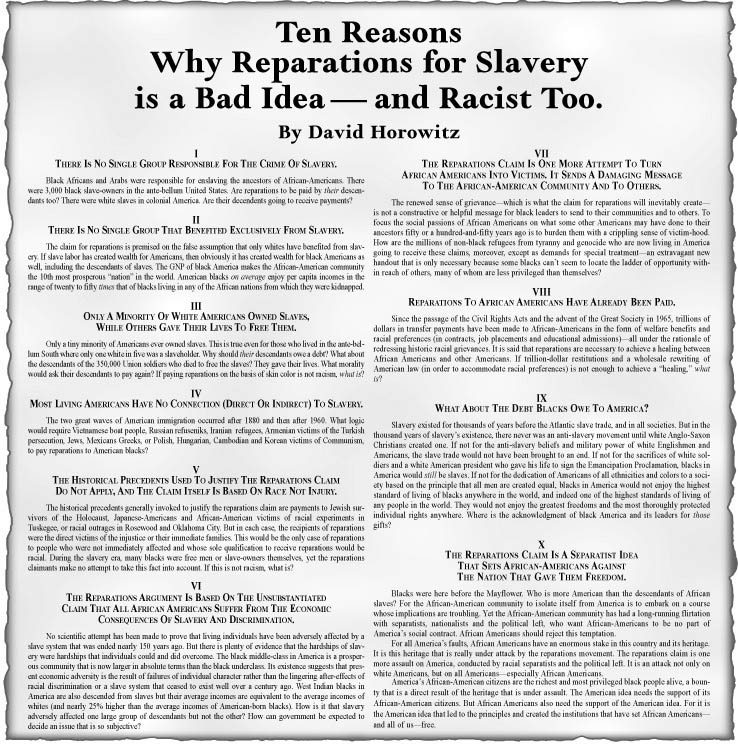

In recent weeks, a debate has raged over an advertisement headlined “Ten Reasons Why Reparations for Slavery is a Bad Idea—and Racist Too.” Horowitz submitted this advertisement to some 50 college newspapers. Of the 59 papers that have received the ad, 14 have printed the ad and 35 have rejected it. This series of events raises serious questions about the role and ethical decisions of campus news media.

The Law

Two Supreme Court decisions directly address the rights of student journalists. In 1969, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, students were suspended from school for wearing black arm bands in protest of the Vietnam war. The Supreme Court said that school officials could only limit student free expression when they could demonstrate that the expression in question would cause a material and substantial disruption of school activities or an invasion of the rights of others.

In 1988, the Supreme Court modified its protection of student newspapers and ruled that the rights of public high school students are not necessarily the same as those of adults in other settings. In the Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier decision, the Court said that a different test would apply to censorship by school officials of student expression in a school-sponsored activity such as a student newspaper. When a school’s decision to censor is “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns,” it will be permissible. The Court found that it was “not unreasonable” for the principal to have concluded that “frank talk” by students about their sexual history and use of birth control was “inappropriate in a school-sponsored publication distributed to 14-year old freshman.”

The Law of Private Institutions

The first amendment protects freedom of expression and is a principle that commands broad respect in our society, in particular in higher education, where the “give and take” of differing ideas is considered essential to learning. From the earlier days of American history, newspapers have had considerable influence in the development of new ideas about national culture and government. Thomas Jefferson once said, “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

But the Constitution only directly binds officials of state and the federal government. At private universities, officials may limit the bounds of free speech and may set guidelines for student and faculty conduct that are more restrictive than those allowed on public campuses.

Despite the fact that the law does not extend the same protections to speech and press at private universities, these freedoms occupy such a central place in American conceptions of democratic tradition that most university officials are reluctant to limit forms of expression.

Derek Bok, past president of Harvard University, once said that he had “great difficulty understanding why a university such as Harvard should have less free speech than the surrounding society—or a public university.”

According to the Student Press Law Center, a private school which seeks to censor its students, prohibits the free flow of information and knowledge which are arguably essential aspects of an institution of higher education. Stifling the free flow of ideas seldom contributes to learning as it has been conceived of at the university level. In fact, the SPLC says censorship prohibits students of a private school from receiving an equal education to students in public schools.

“Because many private schools are church affiliated, and because religious institutions are protected in their expression of belief, the First Amendment should create a common bond with journalists and their free expression rights,” said a document by the SPLC on private school publications. “If it were not for the First Amendment and its protections for the free exercise of religion, many of the schools themselves might not exist.”

Georgetown’s Policy

In January 1989, a committee comprised of four faculty members and four undergraduate students developed guidelines for speech and expression derived from the concept of what a university is and should be. The committee found that free speech is central to the life of the University.

“A university is many things but central to its being is discourse, discussion, debate: the untrammeled expression of ideas and information.” Therefore, the committee ruled that prohibition of free speech, contradicts the very nature of a university. “[T]here is the assumption that the exchange of ideas will lead to clarity, mutual understanding, the tempering of harsh and extreme positions, the softening of hardened positions and ultimately the attainment of truth.”

Georgetown’s Speech and Expression policy guarantees all members of the academic community the right to freedom of speech and expression. “This freedom includes the right to express points of view on the widest range of public and privat\e concerns and to engage in the robust expression of ideas.”

But this freedom is qualified in two manners. First, the right to free speech does not include activity that endangers or threatens to endanger the safety of any member of the community of any of the community’s property. Second, expression that is indecent, obscene or offensive on matters such as race, ethnicity, religion, gender or sexual orientation may be ruled inappropriate.

According to Vice President of Student Affairs Juan Gonzalez, the University works to uphold a liberal freedom of expression policy.

“Issues of us being a Jesuit institution would have to go into making a decision [on freedom of speech],” Gonzalez said. “We decide based on what would be best for the university as a whole.”

The Role of Campus Journalism

Campus newspapers should perform a number of vital services, some of which may appear rather mundane but are of great importance in community life. Student newspapers get the word out about events on campus—all the way from announcing lectures and concerts to notifying students of potential dangers and problems, such as crime. These newspapers, while primarily serving students, also pass news and views among different campus constituencies: faculty, staff, students, administration and alumni. The student press provides an overall calendar of events, and finally also records the university history for future generations.

According to Mark Goodwin, executive director of the Student Press Law Center, a campus newspaper should provide information to their community and encourage debate and discussion on important issues.

Campus press should also serve goals beyond the daily calendaring of events. In many ways, student newspapers embody the ideals of liberal education: exposure to a range of ideas makes men and women more thoughtful, more far sighted and more tolerant. The exchange of ideas involved in a student newspaper helps young men and women understand the issues affecting their lives and make decisions about where they stand in relation to the difficult conflicts that face every generation. The student press helps teach democratic values by promoting the freedom to express ideas and theories.

Encompassing both these roles and ideas about student press, one might argue that student press helps to bind campus communities into a whole. It helps students to understand themselves within the context of campus culture—the particular culture that distinguishes each campus.

The student press builds a sense of community. Readers and viewers learn what they have in common, and they learn how they are different. They see where they agree and where they disagree and can participate in discussion. A student press provides diversity, involves people, encourages discussion, entertains, persuades, interprets and shares school culture.

The Ethics of Student Journalism

Playing these roles places student journalists in the position of making a wide range of ethical decisions every day. The quality of the discourse tells students something about themselves as a community. The standards of civility, intelligence and perspective reflected in campus journalism impacts the quality of discourse throughout the campus. Sometimes, decisions about what to print and how to present an issue can have very significant consequences on the outcome of questions facing campus faculty and administration.

Campus newspapers are known for challenging authority, for expressing unorthodox positions and occasionally for using “shock tactics” to attract attention to certain problems. Whatever the tactics for attracting readers, student journalists are bound by a code of ethics that they should respect accuracy, fairness, honesty and objectivity.

A number of different “niches” exist that student newspapers can occupy. For example, not every newspaper has to aim for the balance of the New York Times. There’s also a legitimate and important function served by The Weekly Standard, The Nation and Mad magazine.

Georgetown’s Student Newspapers

Georgetown University has numerous publications intended for staff, professors, students and administrators. The three most widely distributed school sponsored student newspapers are The Hoya, The Georgetown Voice and The Georgetown Independent. Though all state an intended goal of bringing news to the Georgetown community, each paper was founded under different circumstances with slightly different targeted aspirations.

The Hoya

The Hoya was founded on January 14, 1920 by Joseph R. Mickler, Jr., (CAS ‘20). Mickler founded The Hoya to be more comprehensive than previous Georgetown papers and was intended to serve the College, as well as the law, dental, medical and foreign service schools.

During the 1963 and 1964, Hoya editor-in-chief John Glavin (CAS ‘64) said that the paper’s philosophy during his tenure was “for students, about students, by students.”

According to Don Casper (CAS ‘70), Hoya editor-in-chief during the 1968-69 school year, there was a split in journalistic philosophy among Hoya staff.

“I took the view that our financial resources and our human resources required that we focus on University events because that is what we could do well,” Casper said. “The founding staff of the Voice took that view that given the tumultuous events that were shaking the country, a campus publication had to look outward beyond the University walls.”

Casper said he recognized the importance of national news for students, but he felt students had special insight into university events and lacked the same depth in national events.

The Georgetown Voice

The Georgetown Voice was founded on March 4, 1969 by Stephen Pisinski (CAS ‘71). The debut editorial explained the Voice’s goals and purposes. “Our editorial policy will view and analyze issues in a liberal light. We shall not limit our editorial content to campus topics. We promise to present and analyze national and local issues of concern to the student, whose concern should spread beyond the campus.”

The Voice’s first stories focused on covering events of national significance which didn’t merely touch students’ lives but deeply affected students.

“It was the height of the Vietnam war and Lyndon Johnson had just abolished student deferments. This was not just simply an intellectual interest in an event swirling outside the campus, this was an issue of deeply personal interest,” Casper said in a recent interview.

The Georgetown Independent

The Georgetown Independent was founded by Jeff Burk (LAW ‘98) and Rob Hegblom (CAS ‘97) in November of 1995. According to Burk, Hegblom was not satisfied with the investigative journalism of The Hoya and the Voice, and he decided a conservative voice in Georgetown’s campus media was needed. The first edition of The Independent focused on the discussion in the English department of abandoning the requirement that students take a course in Shakespeare. Burk said the members of the Independent felt the other papers had effectively reported on the procedural aspects of this decision, but he said an investigative article was needed, examining the motives and opinions of those involved.

Until 1997, the Independent was assembled once a month in dorm rooms and apartments and printed by a Virginia-based company. In 1998, then editor-in-chief Mike Nardis, decided to request University recognition and funding and move the paper’s production to an on-campus office. Burke said this change was a harbinger of the Independent’s future; moving on campus restricted the paper’s ability to have an ideological viewpoint and meant it was compelled to open membership to the entire student body.

According to current editor-in-chief, Meghan Conaton (CAS ‘02), because the Independent is such a young paper, it is still working to establish a stable identity. Conaton said the mission of the paper has changed with growth; she sees the paper as being an in-depth, investigative publication to provide a “common sense voice on campus.” Conaton said though the news is now completely unbiased, the final three pages of the Independent, the commentary, may take a conservative slant due to the views of the writers.

Controversy in Student Journalism

Horowitz’s advertisement explained why reparations for African Americans is a bad idea. The ad claimed no group is responsible for slavery, few Americans owned slaves, and African Americans owe the United States gratitude. It

also argued that reparations turn African Americans into victims, whoshould actually be thankul to those who gave them freedom.

Horowitz’s ad was arguably intended to provoke controversy. Recent debate on college campuses has centered on freedom of speech vs. political correctness. Horowitz has long been a challenger of politically correct behavior and language on college campuses and in campus media. And this episode definitely seems to test whether a desire to be politically correct inhibits the freedom of speech and the freedom of press described in the First Amendment.

Although Horowitz’s ad definitely provokes controversy, and some may feel it is obviously incorrect in its assertions, the ad presents an opinion of an act: a statement usually protected by the First Amendment. In a speech at the University of Texas School of Law, Horowitz said the reparations claim is an attempt to turn African-Americans into victims.

“The reason I responded at all is because I thought black leadership was doing a great disservice to the African-American community,” Horowitz said in an article in the Daily Texan, the newspaper at the University of Texas at Austin. “It causes antagonism between races, and if you don’t feel a part of something, that will hold you back.”

This predicament has forced many top editors at college newspapers to evaluate the ethical decisions of their paper and decide whether or not to run Horowitz’s ad. At Georgetown, an institution of higher education that prides itself on free circulation of every idea and opinion, how would Horowitz’s ad, or a similar ad, be received?

Hoya response

Tim Haggerty (CAS ‘02), Hoya editor in chief, in a March 27 article in The Hoya, wrote that he would advocate running the Horowitz ad, to “affirm the tenets of professional, responsible journalism.” Haggerty’s central reason for running the ad is that there is no reason for it not to run. “In making their decisions, newspaper editors should consider taste, ethics and laws—and apply these principles to the specific ad in question,” Haggerty wrote.

Haggerty emphasizes that it is in a reader’s interest to be exposed to all sides of an argument. “To pull the advertisement for reasons besides these would be to make a political statement and demonstrate an organizational bias, the worst enemy of an objective newspaper,” he wrote.

The Hoya’s editorial staff disagreed with Haggerty, deciding that “ad space is an inappropriate venue for airing political views.” The board determined that a political interest should not be able to buy space in the newspaper, and instead should submit such pieces to opinion-oriented sections.

Though The Hoya has not received Horowitz’s ad, the final decision of whether to run the ad would be made by a vote of the paper’s Board of Directors.

Voice response

Voice Editor-in-Chief Joe McFadden (CAS ‘02) said he would run the Horowitz advertisement because freedom of speech should be the primary focus of every action a newspaper takes. McFadden said this freedom should apply to both advertising and editorial content.

“To the extent that a newspaper’s actions are contrary to freedom of speech, that newspaper is in danger of violating the fundamental right that allows it to exist in the first place,” McFadden said.

The Voice editorial board agreed with McFadden that the ad should be run. The board stressed the importance of the distinction between journalistic ethics and individual moral values.

“Any advertiser who operates within the confines of free speech as determined by editors and courts should have equal opportunity to buy space within a newspaper,” McFadden said.

In the case of controversial ads, the Voice editor in chief is responsible for bringing the ad to a vote by the General Board.

Independent response

Meghan Conaton, Independent editor-in-chief said she would run the Horowitz ad to protect the princple of free speech. Conaton points out that advertisements are a means to a newspaper’s end, to publish issues that inform readers.

“[A] publication should prove its worth to its community by remaining unbiased and impartial to any one part of its readership,” Conaton said. “Individuals may be incapable of such neutrality, however, when individuals come together to form the institution of a newspaper, that neutrality is vital. Without it, the institution can no longer claim any journalistic intergrity.”

Burk, as a founder of a paper intended to include a conservative slant, said he does not know if he would run the ad. Burk said he does not support slave reparations, and thus does not object to the opinion expressed in Horowitz’s ad. However, concerns over the reputation of the paper if the ad were to run would perhaps prevent Burk from running the ad.

“I don’t think he should be silenced just to not hurt people’s feelings,” Burke said. “If you don’t agree, you should come out and publish a rebuttal. Particularly on college campuses, the broader the debate, the better.”

The structure of the Independent’s editorial board bestows final decision-making power to the editor-in-chief.

Georgetown’s response

According to University policy, the Vice President for Student Affairs can make the decision to revoke an advertisement from running in a campus newspaper.

Juan Gonzalez, the Vice President for Student Affairs, said he supports full freedom of expression, but he would have to consider Georgetown’s Jesuit identity before making a decision on a controversial ad. Gonzalez said such a controversial issue could only be decided on a case by case basis, and with a great deal of scrutiny, debate and analysis.