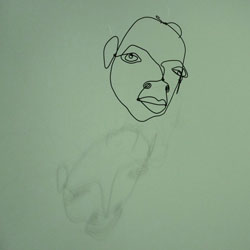

History may have awarded John Hancock and Queen Elizabeth with fame for their bold and ornate signatures, but sculptor Alexander Calder deserves points for creativity—when signing his works, Calder brandished cold copper wire as elegantly as any calligrapher. In sculpting wire portraits of famous people, which lack any trace of a brush or a stone surface, Calder marked each of his wire sculptures with an inventive inscription. Woven behind an earlobe, under a chin or at the base of a neck, Calder looped wire to form his signature on each of his whimsical wire portraits.

These wire portraits are the subject of Calder’s Portraits: A New Language, on display now through August 14 in the National Portrait Gallery. Although best known for his invention of the mobile as a form of sculpture, Calder also crafted a prolific set of three-dimensional, caricature-like, copper and steel wire portraits throughout his career. The exhibit highlights this delightful, though often overlooked portion of Calder’s canon.

The gallery divides Calder’s works roughly by the profession of the subject, with portraits of actors, athletes, and fellow artists each displayed in a room of their own. However, Calder also sculpted portraits of subjects he knew personally, and as a result, portraits of Calder’s neighbors and cousins strangely appear among the wire visages of Babe Ruth and Jimmy Durante. The not-quite-perfect organization that arises from Calder’s mix of subjects nicely breaks up the rigidity of the gallery, allowing space for unknown but expressive faces to shine.

Situated at the entrance of the gallery, Calder’s portrait of Slavoljub Eduard Penkala sets the tone for the rest of the exhibit with his warm, wire smile. Though Calder did not immortalize the inventor of the first solid-ink fountain pen in his own medium, wire serves Penkala well—the inventor’s square face and bright eyes pop from their copper threads, suggesting a playfulness of character in a man who spent his years innovating the designs of the modern mechanical pencil.

Just as in Penkala’s portrait, Calder expertly captures the character of former president Calvin Coolidge in his own wire doppelganger. Crafted with a single, thick steel wire rather than a multitude of thinner, copper threads, Coolidge’s portrait accentuates his striking, expressive facial features. Beside the portrait, the gallery notes that “especially in his early wire portraits, Calder straddled the line between portraiture and caricature.” The artist himself described his methods by saying that “where you have features, you draw them; where there aren’t any, you let go.” Coolidge’s exaggerated portrait speaks strongly to this mantra.

But although Calder’s curling wires give life to his subjects, the National Portrait Gallery misses an opportunity to present the artist in his full character. Calder himself often hung his wire creations from walls and ceilings, allowing the portraits to dangle and spin, just as his mobiles did. While two of Calder’s portraits are presented suspended from the ceiling, the rest sit boring and immobile in plexiglass boxes on simple white stands.

But despite their presentation, Calder’s portraits still reveal the artist’s playfulness just as well as the subjects they represent. Calder would often craft miniature wire carnival models as a hobby, claiming the title of “ringmaster of the Lilliputian circus.” The swirling copper and steel wires of Calder’s portraits similarly indicate that this artist clearly took great joy from his creations.