On November 18, 1985, Bill Watterson published the first part of Calvin and Hobbes, a comic strip that would run for 10 years. The series follows the adventures of the misbehaved Calvin, a young boy, and Hobbes, the anthropomorphic vision of his favorite stuffed animal, a tiger. The series continues to be extremely popular beyond its last issue, published in 1995.

There are frequent references to the series across pop culture, and a particular crowd of fans suspect that the series inspired Chuck Palahniuk’s critically acclaimed, 1996 novel and its 1999 adaption, Fight Club. The film is considered a masterpiece with its disturbing nature garnering a cult following that has latched on to the film’s aggressive, counter-culture messages.that promotes anti-societal messages. Nonetheless, there is a theory that the inspiration behind the work, from its literal to its philosophical roots, is Watterson’s cartoon series.

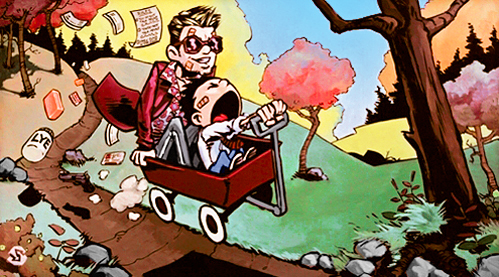

Fight Club’s protagonist, The Narrator (one should note the ambiguity of the character not having a name), is portrayed by Edward Norton, and is actually intended to be an adult version of Calvin. The film takes place at the onset of “Calvin’s” mental break that reintroduces him to his “Hobbes” in the form of Tyler Durden, played by Brad Pitt.

The core principle of both narratives is that the main characters have created versions of themselves that embody all the qualities they aspire to have. Calvin is a tad rambunctious, does poorly in school, and seems to aggravate his parents. Hobbes is more reserved and seems to have a better grasp of good decisions and common sense. The Narrator is timid, reserved, and leads a very mundane life. Tyler, on the other hand, is a constant source of excitement who does not care at all for any rules and does exactly what he wants.

Deep down, both “real” people wish to become these idealizations. Neither really have any friends, and one can clearly note that the two protagonists already have escapist personalities. Nearly every comic strip is a different scenario of Calvin’s imagination. Many strips are about his alter egos “Space Man Spiff,” “Tracer Bullet,” and “Stupendous Man.” It is easy to parallel that with The Narrator’s dependency of terminal illness support groups. He literally becomes an insomniac unless he escapes into this pity-filled pseudo-reality.

Although there are many personality traits, Hobbes and Tyler are the forms that can get the girl, Susie or Marla, respectively. Beyond the similar looking, disheveled appearance and confident attitude, both play a similar role for the sake of each story. Susie always interacts with Calvin through a sporadic love-hate (mostly hate) relationship and always acts lovingly towards Hobbes. In the Fight Club universe, Edward Norton’s character is forced to constantly hear his alter ego and Marla having sex while he takes a passive intrigue in her. Love, in any manner that it may be interpreted, is an extremely powerful emotional trigger, even enough to concoct a “better” version of one’s self.

The idea of the fight club itself is a direct disambiguation of Calvin’s childhood aspirations. As odd as it may seem, Calvin and Hobbes liked to fight each other. There are countless strips spent with storyboard scene after scene of the two tackling and wrestling each other. In the comics, Calvin makes an all-male, secret society, G.R.O.S.S. (Get Rid Of Slimy girlS) that plans “sneak-attacks” against Susie. Although this a far stretch from rolling a giant sculpture piece through a coffee shop, it is similar enough to be a six-year-old version of the Narrator’s starting off point. Watterson and Palahniuk relay action with such confidence that it is hard to realize that the character goals are utterly absurd tasks. Calvin’s construction of an army of snowmen that quickly turn against him is just as absurd as breaking into a liposuction clinic dumpster in order to make soap for a profitable business.

In terms of general setting and plot details, one should note the ambiguity. The Narrator and Calvin are perpetually in fantastical worlds of their own concocted illusions. Therefore, there are no definite places in either circumstance. This lack of specificity passes on to ideas of controlling figures as well. Calvin’s parents are never given names through the series. Instead they are merely “mom” and “dad.” In the same way the dull job that Edward Norton holds is for an automobile company. When asked which one, he only replies “a major one.” Both have clear problems with authority as well. Calvin and his teacher versus the Narrator and his boss is a prime example of this.

Both stories have largely different degrees of disturbing within them, yet there is one more innocent principle in Fight Club that Calvin and Hobbes always seeks to capture: the resistance to growing up and adulthood. Tyler profoundly hates consumerist society. His goal is to destroy large corporations and this brainwashed, worker bee attitude that all people have bought into in this day and age, “Advertising has these people chasing cars and clothes they don’t need. Generations have been working in jobs they hate, just so they can buy what they don’t really need.”

The whole idea behind the end sequence, “Project Mayhem” is to erase all debt in the world by destroying credit card record buildings. his eliminates all the strains and struggles that plague the adult world. The Narrator/Tyler is Calvin/Hobbes. The kid who never wanted to grow up. He is merely an adult version that forgot about his previous resistance to growing up, and a brilliant mental relapse gave Palahniuk the excuse to create this instant cult classic.

Photo: tumblr.com