Halftime Sports Editor Matt Jasko examines the intersection between finance, economics, and athletics in his segment, “The Cap.”

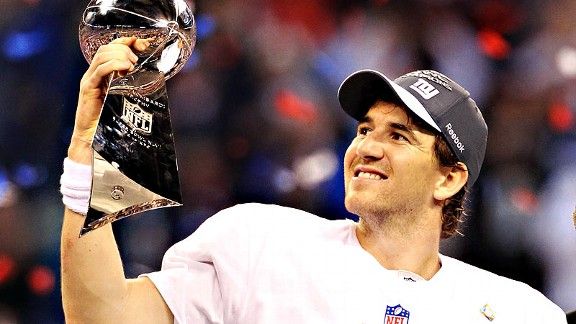

Three developments dominated the discussion of the New York Giants’ 2015 offseason: Jason Pierre-Paul’s hand and the finger pointing (no pun intended) surrounding it, Victor Cruz’s return from an on-field injury, and Eli Manning’s contract extension. As for the first two developments, only time will tell how fast and to what degree the two superstars heal, but the third is in the books.

On September 10th the 34-year-old Manning signed a four-year, $84 million ($65 guaranteed) extension with Big Blue. The final clause of the contract to be agreed upon was that of a no-trade clause for Eli, an extremely rare concession made by the Giants.

As every contract in New York undoubtedly does, the inking of this deal sparked an instantaneous media firestorm and subsequent public debate. To make some sense of the arguments let’s take an objective look at Manning in the context of the deal.

In order to do this, we must first establish what the Giant’s goals are in signing a quarterback. Contrary to the fantasy many football fans live in (sorry, getting carried away with the puns), the object of an organization in signing a quarterback is not inherently to rack up massive numbers of passing yards and Quarterback Rating statistics; rather, the goal is to move the organization closer to being a perennial Super Bowl contender.

Therefore, we must evaluate how far the traits Manning brings to the table push the Giants towards the said goal. Furthermore, in order to determine the relative value add/loss of Manning relative to his contract, we must put his contract in the context of other recently signed quarterbacks.

The first trait among those we should look at for the purpose of moving the organization towards the ultimate prize is that of franchise wins relative to another quarterback; after all, it’s impossible to win the Super Bowl if a team can’t get there.

Looking at wins relative to another quarterback is difficult to do because the only way to truly prove how many wins an organization would have with a different man under center is to go back in history and plug somebody else in, which is of course impossible.

However, we can still build a reasonable regression to determine the efficacy of Manning relative to the rest of the league. The ideal way to go about this is to start by measuring team performance over Manning’s playing time (we will proceed to refine independent factors as time goes on.) Furthermore, we will compare these factors to the other quarterbacks who have recently signed four-year deals- Russell Wilson, Philip Rivers, and Ben Roethlisberger, to establish relative value.

With Manning under center the Giants are 101-82 (.552), a slim but yet measurable difference above the average .500. By comparison Wilson has a .721, though only 44 wins because of the far shorter time he has played. Roethlisberger and Rivers, who came into the league the same time as Manning, have 117 (.661) and 94 (an injury-shortened .603) wins respectively (all stats are regular and post season combined).

Additionally, in the ten full seasons Manning has started the G-Men have gone to the postseason five times, good for a .500 percentage. With six of the 16 teams in the conference reaching the postseason, the expected average would be .375. Roethlisberger has been to seven in 11 years starting (.636), Rivers has been to five in 10 (.500), and Wilson has been to three in as many seasons (1.000)

Moving forward, Eli Manning has a Super Bowl percentage (percentage of season team wins Super Bowl when quarterback starts) of .200. This towers above the 32-team league average of .03125, indicating the Giants have won Super Bowls at a frequency 6.4 times above the league average during Eli’s reign. Wilson matches that stat of .200, followed by Roethlisberger a .181, and then Rivers at .000.

These statistics give us the picture of how successful each quarterback’s team has been during his tenure; however, to make these statistics truly significant we must isolate the quarterbacks relative to the other players on the roster who have also contributed to the team statistics. To do this we examine a series of statistics, the first of which being offensive personnel and coaching turnover.

The logical place to start in this regard is with Manning’s first season, 2004. No other players from that 2004 team have remained current to the 2015 Giants. Likewise, no players from Big Ben’s or River’s rookie year in 2004 remain either. This is not surprising given the turnover rate in the NFL, but it is nonetheless important to note the distinct isolation of these variables. Wilson, who came into the league far later, cannot be compared in this respect.

In terms of coaching there are two major constants who remain- Tom Coughlin and Pete Carroll. In the case of Wilson, he has also had the same offensive coordinator his entire career. This could be problematic if any of the combinations were separated, but for the purposes of at least this season all the coaching/ quarterback combinations that could be interdependent are still intact. Also, every quarterback except Wilson has proven the ability to succeed under different offensive coordinators.

The next place to look at turnover specific to Manning is between his two Super Bowl championships to isolate his role in those.

On the championship Giants teams there were three offensive starters other than Manning who remained constant- offensive linemen Chris Snee, David Diehl, and Kareem McKenzie). The Giants also maintained running backs Ahmad Bradshaw and Brandon Jacobs, who switched starting capacities. The only receiver on the team who remained constant was largely a special teams contributor- Dominic Hixon.

The most accurate measure of comparison to judge this turnover against is that of the Pittsburg Steelers between 2005 and 2008. There are the only other team to win multiple Super Bowls in the decade from 2005-2014 (though the Patriots form bookends just outside this decade), they did it at a similar margin as the Giants (three years compared to four), and Roethlisberger is one of the main quarterbacks we are using to measure Manning’s relative success.

Between the Pittsburgh championship years the Steelers likewise returned three starters. However, unlike the Giants who returned no skill starters, Pittsburgh returned nothing but skill- Willie Parker, Hines Ward, and Heath Miller. Furthermore, the Steelers also returned three offensive linemen- Max Starks, Kendall Simmons, and Marvel Smith- though their starting designations had become reversed over the time period.

In short, both teams returned three offensive starters and six overall offensive contributors. The arguments could be made that the lack of skill continuity and extra year of separation between titles reflect better on Manning or the lack of head coach and offensive coordinator continuity makes Roethlisberger more impressive. However, on the whole the comparison demonstrates both quarterbacks had relatively similar rates of turnover around them. This indicates that as we continue to regress individual contributions, the Super Bowl years should be in line, if not even more powerful statements of, what we find going forward.

With that in mind, it is then necessary to determine how much turned over players benefit from coming to a team/ are hurt by leaving one. This will help us isolate the true quality of a quarterback’s offensive supporting cast (we can’t just use raw statistics because we must separate the effects of each individual player on the team, and raw statistics feed off symbiotic relationships between players). We can achieve our purpose by comparing skill position players’ performances while on a team against their performances with another, assuming their age remains comparable.

There are a long list of Giants offensive players who have performed dramatically better wearing blue than they did in other places: Hakeem Nicks, Steve Smith, Mario Manningham, Kevin Boss, Brandon Jacobs, Ahmad Bradshaw, and Derrick Ward. Of course, some of these can be watered down by injury, but not completely and not all of them. Especially considering looking at the converse list- Giants on the offensive side in the ball who did not play well during the Manning era but did elsewhere: Ryan Grant. And at that, Grant was only a practice squad player in New York (never actually technically even on the Giants roster, similar to an early Victor Cruz), and he only had two 1,000 yard rushing years before it was all said and done. (While on the subject of Cruz, we should also note Cruz was an undrafted free agent turned star while playing with Manning.)

Under Roethlisberger Santonio Holmes was most significant drop-off after leaving the Steelers; under Rivers Tomlinson experienced a significant decline after leaving (though age started to come into play), and Wilson’s short career has not yet indicated any players his playing may have directly and significantly benefited. These lists are purely subjective and could of course be altered by individual observers, but the great volume of players who succeeded in New York and then failed elsewhere relative to the lists of players in Pittsburgh, San Diego, and Seattle bodes very well for Eli.

The converse of this argument has often been used to bolster Tom Brady in comparisons- the idea being he is impressive because can win without great skill players around him; however, perhaps more impressively and undoubtedly far under looked is the ability of a quarterback to make average and even below average players into key pieces of championship teams. This is an area in which Eli Manning excels.

Furthermore, in addition to offensive turnover, one must take into account the defenses each quarterback had to work with; it is after all far easier for a quarterback to win if he does not need as many points. Because the game has changed between the class of 2004’s rookie year and Wilson’s playing time (pass interference, late hits, defensive penalty yardages, etc.), it is more accurate to look at average defensive rank than average points or yards.

In terms of points per game ranking Russell Wilson has had a great advantage- the Seahawks have been the #1 defense in the league all three years he has started. Not far behind, the Steelers have averaged 6.4th in the league over the past 11 years Big Ben has been under center. Over Philip Rivers’ tenure the Chargers have been the 12.2nd ranked D in the NFL. The only quarterback who has had a below average defense on average has been Eli, who has had the 18.4th defense on average.

Moreover, these averages become further polarized in Super Bowl years. When Wilson won the big one, he had the #1 defense (as he has every year of his young career). In Big Ben’s two trips, he had the #1 and #3 defenses, averaging 2.0. Manning on the other hand won it all with the 17th and 25th ranked regular-season defenses, an average of 21.0 (all stats based on points against per game ranking).

Furthermore, one can continue to delve into the surrounding talent of each Super Bowl team by examining the number of true superstars- players who make the Pro Bowl. While Pro Bowl selections are often arbitrary and are by absolutely no means the be all and end all, they do tend to reflect raw statistical performance. Furthermore, large differences between the number of selection per team can indicate rough talent levels. Such is the case with the Super Bowl teams in question.

There were a grand total of two Pro Bowlers (not counting Eli) BETWEEN both Giant championships (Osi Umenyiora and Jason Pierre-Paul). In contrast, Roethlisberger had eight (Alan Faneca, Jeff Hartings, Joey Porter, Casey Hampton, Troy Polamalu x2, James Farrior, and James Harrison) between his two championships, and Wilson had five (Marshawn Lynch, Max Unger, Richard Sherman, Kam Chancellor, and Earl Thomas) for his title.

Those defensive and supporting cast statistics make Manning’s long list of accolades more impressive. These include: NFL active leader/ third all-time in consecutive starts (178), NFL record fourth-quarter touchdown passes in a season (15), NFL record road playoff wins (5), NFL record single postseason passing yards (1219), and tied for NFL record game-winning drives in a single season (8).

This is not to say that the other three do not also have long lists of accolades. Roethlisberger threw over 500 yards twice and 6 TDs in consecutive game. He also holds many early career honors his ridiculous early career stats. Rivers went five straight games with a passer rating over 120 and threw for 400 twice in a row. Wilson had arguably the best single-game postseason performance by a rookie quarterback and has already been to two Super Bowls. However, the teams that each player accomplished these things with must be taken into account, as well as the locations in which they did it.

In this respect, Eli accomplishing what he has in New York is remarkable. From dealing with his own early career interception struggles, to negative comments from former player Tiki Barber, to the attitude of Jeremy Shockey, to the stupidity of Plaxico Burress all being blown up by the New York media, Manning has done phenomenally, as made evident by his rings and accolades. Each of the other three have also obviously dealt with adversity, but the markets of Seattle, San Diego, and Pittsburgh are laughable in comparison to a New York market that magnifies everything.

With all of these factors in mind, it is time to more closely examine each contract. Though Manning’s $84 million total puts him in the lower half of this small group, two factors have been pointed out as making his deal more imposing- his guaranteed money and his no-trade clause. At $65 million guaranteed only Rivers equals him, and none of the other quarterback have a no trade clause.

Wilson has a financially similar deal at $87.6 million with $61 guaranteed. Roethlisberger is a shade off in total money at $87.4 million, of which $61 million is also guaranteed. Rivers trumps everyone but Manning in guaranteed money, though he maxes out at the lowest mark of $83.25 million.

These statistics indicate that the Giants have a great deal of respect for Manning but have stayed within market value. The no-trade clause is the shining piece of the deal, demonstrating the Giants intend to have Eli Manning play quarterback for them over the next five years. This also carries less risk than one may think because it is extremely difficult to offload a contract anywhere near this size in a trade anyway.

The guaranteed money also exhibits further reverence for past accomplishments which, contrary to many opinions, should be paid in contracts; signing franchise players down the line becomes easier if they believe they could someday re-sign another contract at a healthy salary. (In Manning’s case the guaranteed money is also relatively safe considering he hasn’t missed a start in 10 years.)

However, the Giants have also caped their risk. At $84 million Manning’s max is in-line with the others. Furthermore, the term running out when Manning is 38 is a far safer proposition for New York than an extra year would have been.

The biggest bone to pick for Eli detractors is the $4 million difference in guaranteed money between Manning and Roethlisberger. However, take into context the rest of the league—Wilson like Big Ben has $61 million, and Alex Smith and Ryan Tannehill, who each also recently signed four-year deals, have $45 million. Within this overall context and the relative efficacies of each quarterback (four of which we have demonstrated), the figures make sense.

With all these factors in mind, it seems that Manning’s deal is financially even with the market and inherits an acceptable degree of risk from a football standpoint. A no-trade clause proves respect for what Manning has done, and it likely does not hurt the Giants because unloading that type of contract through a trade is nearly impossible anyway. Though the New York media has extensively covered the deal, as expected, it is on-par with what teams have conceded to re-sign their franchise quarterbacks, the only difference being an in-all-likelihood irrelevant no-trade sign of respect for the man who has won MVPs in half of the franchises’ Super Bowls.