In the early days of James Bond, the protagonist was based around a very simple idea: women wanted him, and men wanted to be him. Surprisingly enough, this was never the intention of Ian Fleming, the character’s creator. In a 1962 interview with The New Yorker, Fleming said that he wanted Bond to simply be a “blunt instrument,” a boring and static central character in a dynamic and exciting world. The name “James Bond” came from Fleming’s desire to reinforce just how boring the character was going to be, as he felt that it was the most uninteresting name possible. An avid bird-watcher, Fleming took the name of James Bond from an American ornithologist of the same name.

Despite Fleming’s original intentions, the character of James Bond has become one of the most iconic and recognizable characters in film history. Also known as 007, Bond has been portrayed by six actors over the franchise’s 53-year lifespan, each bringing his own interpretation to the character. From the suaveness of Sean Connery to the tongue-in-cheek humor of Roger Moore to the brutishness of Daniel Craig, Bond has endured throughout decades of production issues, box-office disappointments, and Madonna singing the theme song for Die Another Day (and cameoing in the film as well!).

cinestar.hu

It all began during Fleming’s time in the Naval Intelligence Division during World War II. He drew from the characteristics of various agents and operatives he met during his service. After the war, he expressed a desire to write a spy novel, an objective he achieved in 1952 when he wrote the first Bond novel, Casino Royale. That novel spawned a series of books which became almost instantly popular around the world.

Bond was first adapted to the screen in 1954 when CBS bought the rights to Casino Royale and produced a one-hour special based on the book. In 1959, producer Henry Saltzman purchased the rights to some of Fleming’s novels, sensing the chance for a film franchise. However, Saltzman feared the character would be too foreign and too sexual for American audiences, and was hesitant to push for a film to go into production. Albert R. Broccoli, another producer, approached Saltzman about buying the rights from him, and the two decided to form a partnership. They created two companies: Eon Productions, which would produce the films, and Danjaq, which would hold the film rights. The two also partnered with film studio United Artists, which agreed to provide funding for the first film and also bought the rights to seven Bond novels. United Artists would later partner with MGM to co-distribute the films.

Originally, Broccoli and Saltzman intended to turn Thunderball into the first film, but Fleming was in the midst of a heated battle over the film rights to Thunderball with co-writer Kevin McClory. Thus, Broccoli and Saltzman settled on producing Dr. No in 1962 as the first Bond film. United Artists provided the production with just a one million-dollar budget, which was extremely small for a spy movie. The screenplay made several significant edits to the novel, such as removing a fight between Bond and a giant squid, which would have been impossible to film given the production’s limited budget.

Casting Bond proved to be an extremely tricky endeavor. The producers initially wanted Cary Grant for the role, but they weren’t sure if Grant would be willing to sign on for a series of films. They considered a host of actors, including future Bond Roger Moore, before settling on 30-year old Sean Connery, whose suave attitude won them over. Fleming initially disliked Connery’s casting, as he felt that the actor was not sophisticated enough to portray Bond. He quickly changed his mind after Dr. No premiered. Terence Young signed on to direct, and Monty Norman wrote the iconic theme, with John Barry performing and arranging it.

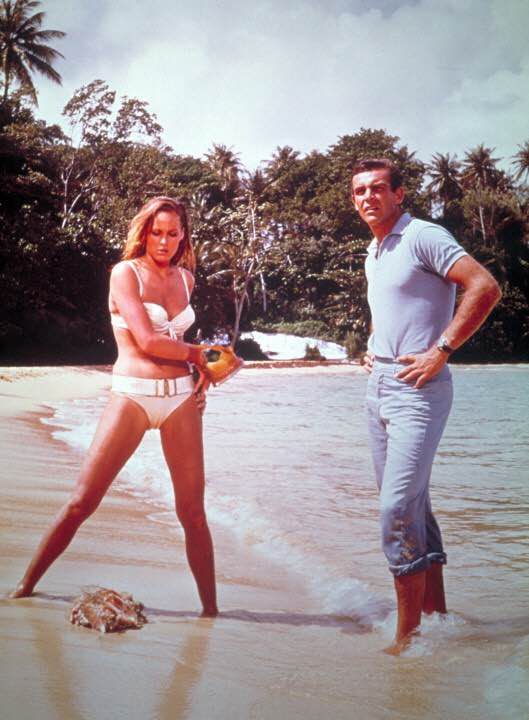

The film set the precedent for most Bond movies since. Bond’s famous introduction scene, in which he utters the immortal catchphrase “Bond, James Bond” while playing cards in a casino was actually lifted from the novel Casino Royale. Joseph Wiseman portrayed the eponymous villain with incredible relish, and Ursula Andress’s famous appearance in a revealing bikini made her iconic as the first Bond girl. The film also introduced the villainous criminal organization known as SPECTRE (which had not been included in the book) in order to set the stage for the following films.

Dr. No. (IMDB)

Despite its low budget, Dr. No is still extremely well-regarded by Bond fans today. It received a mixed critical response, but it succeeded where it really counted: the box office. The film grossed almost $60 million worldwide by the end of its release (and subsequent re-releases), and a sequel was quickly greenlit. United Artists doubled the budget and gave Connery a bonus of $100,000. In an interview with Life magazine, president John F. Kennedy included From Russia With Love among his top-ten favorite books, and Broccoli and Saltzman chose the book as the next movie.

With a larger budget and a set Bond, production was much smoother, and the finished product was extremely well-received. The film was praised, then and now, for its focus on realism, highlighted by an intense, close-quarters fight between Bond and a Russian operative known as “Red” Grant on a train. It was criticized for being poorly paced, but the payoff was considered to be well worth the wait. The box-office returns improved as well: by the end of its total run, From Russia With Love had grossed $95 million. Matt Munro also became the first singer to perform a theme song written specifically for a Bond film. The song played over the opening credits, which followed a brief opening fight scene, as would become standard for subsequent Bond films.

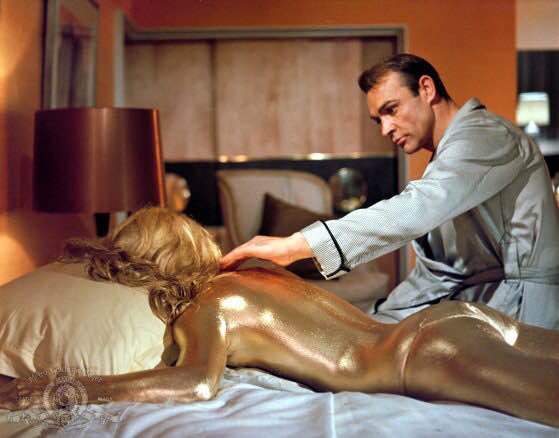

Following From Russia With Love’s success, Saltzman and Broccoli turned to the seventh Bond novel, Goldfinger, as the next story to adapt in 1964. In many ways, Goldfinger became the formula for future Bond films: there was a charismatic villain with an outlandish plan to get rich, a main Bond girl with an absurd name (Pussy Galore), a secondary Bond girl who was killed off in a memorable fashion by the villain (covered with gold), an unusual henchman for Bond to defeat, a pre-credits sequence that had nothing to do with the plot, and an iconic car complete with various gadgetry. Goldfinger was extremely well-received critically and was a hit at the box office, grossing $124 million worldwide.

Goldfinger’s balance of humor and action became the basis for the Bond films to come. Its widespread success led to a Casino Royale spoof in 1967, and it ushered in an era of spy films that dominated the 1960s.

The fourth Bond film, Thunderball, was a product of a long-gestating legal dispute between Ian Fleming and writer Kevin McClory. In 1959, Fleming, McClory, and a third writer (Jack Wittingham) collaborated on a screenplay to turn Bond into a film. However, they could not secure a director, an actor to play Bond, or financement for the production, and the idea was soon scrapped. Fleming took ideas from the failed screenplay and turned it into the novel Thunderball without crediting McClory and Wittingham. In response, the two sued Fleming, and the case was settled out of court. Saltzman and Broccoli navigated this legal quagmire by offering McClory a sole producer credit on Thunderball (Saltzman and Broccoli were credited as executive producers), and the film moved forward for release in 1965. It was received with mixed reviews, but grossed $141 million at the worldwide box office, the most for any Bond film until Live and Let Die. It is noteworthy for its large number of underwater action scenes, which were technical marvels for a 1960s production.

Goldfinger. (IMDB)

Saltzman and Broccoli returned as sole producers for the franchise’s fifth offering, You Only Live Twice. They noticed that Bond was becoming increasingly popular in Japan, and decided to set a large portion of the film in the country. You Only Live Twice was also noteworthy for being the first Bond film to essentially ignore the plot of the novel it was based on, as the producers only chose to keep the villain, the iconic Ernst Stavro Blofeld, and the setting, while changing the rest of the story’s elements. The film was a hit financially and critically, but its aftermath provided the Bond franchise with its first real obstacle.

For fear of being typecast, Sean Connery informed the producers that You Only Live Twice would be his last appearance as Bond. He was tired of the exhausting production and promotion schedules, and wanted to be able to expand his career. Saltzman and Broccoli immediately began to look for a replacement, as Connery had become so disenfranchised from the role that he refused to speak to Broccoli. The pair eventually settled on George Lazenby, an Australian model. Lazenby coveted the part, and insisted on wearing the same suit Connery wore while hanging around their shared barber. Coincidentally enough, Broccoli noticed Lazenby in the barber, and offered him an audition due to his similarities to Connery. During his audition, Lazenby accidentally punched a stunt coordinator in the face, which sold both Saltzman and Broccoli on his ability to perform action scenes.

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was the next release, and it encountered extremely divisive reviews. One consensus among critics, however, was Lazenby’s uncomfortable performance as Bond. The producers liked it enough to offer Lazenby a huge seven-film deal, but Lazenby was convinced by his agent, who believed the Bond franchise would not survive the 1970s, to turn it down. At the film’s premiere, Lazenby arrived sporting an unsightly beard, and refused to shave it at the behest of the producers. He would later state that he came to deeply regret leaving the Bond franchise after just one film (his acting career never took off afterwards).

The film grossed just $64 million worldwide, a financial success, but only half of what You Only Live Twice made. Time, however, has been kind to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Many Bond fans today consider it one of the franchise’s best films, boasting emotional complexity, a great villain, beautiful cinematography, an incredible score, and fantastic action scenes. Unfortunately, Lazenby’s awkwardness weakened the film, as he could pull off the stunts but not the more emotional scenes the film required.

Due to the lukewarm reaction to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the producers aimed to make the next film, Diamonds Are Forever, as similar to Goldfinger as possible in order to win back fans. Connery was persuaded to return to the role thanks to an exorbitant $1 million salary, a record for an actor at the time. Shirley Bassey, who sang the iconic Goldfinger theme song, returned to sing the theme for Diamonds are Forever. Surprisingly enough, the film was not well-received by critics, who criticized its extremely campy tone, a stark contrast to the far more serious On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, but the film was still a hit. It grossed $116 million worldwide. After the film’s release, Connery departed the role, seemingly for good, and the producers were once again left with the task of finding a new Bond.

Unwilling to risk another casting debacle, the producers initially looked for a known commodity to play Bond. They approached Clint Eastwood, but he declined the role, saying that Bond should only be played by an Englishman. Burt Reynolds, Paul Newman, and Robert Redford were all also considered, but the producers finally settled on Roger Moore, who had been considered for Dr. No before Connery took the part. Moore was well-known in Britain for his role as Simon Templar in the hit television series, The Saint.

Live and Let Die was released in 1973 and generally well-reviewed. The film’s racial overtones were criticized, and Moore struggled to win fans and critics alike over with his portrayal of Bond. Paul McCartney’s title song is one of Bond’s most iconic. Still, the film’s action scenes were highly praised and it was a huge hit at the box office, grossing $161 million.

In many ways, Moore saved the Bond franchise. Fans weren’t sure if the franchise could survive in a post-Connery era. Live and Let Die carried a ton of pressure to succeed, and Moore pulled it off. It took him a couple of films to really settle into the role of 007, but once he did, he provided the character was some signature flair. Moore’s performance differed from Connery’s in that Moore proved to be extremely capable of giving Bond a sense of humor and pulling off some classic one-liners. His character was a complete departure from Fleming’s Bond, but audiences loved it. He would also become the longest-serving Bond, starring in seven films. The Moore era would become arguably the smoothest period in Bond’s history.

After Live and Let Die’s success, Moore gave fans a scare with 1974’s sub-par The Man with the Golden Gun. Christopher Lee joined the cast as the villainous Francisco Scaramanga, the titular assassin, but he was just about the only redeeming factor in an overly campy film. Critics derided its silly tone, and it would earn a total of $97 million at the worldwide box office, the franchise’s fourth lowest gross. The Man with the Golden Gun was also the final film co-produced by Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli, as Saltzman sold his shares in Danjaq, leaving Bond in the hands of Broccoli.

The franchise encountered a brief hiccup after the lukewarm reception to The Man with the Golden Gun. It had not been very successful at the box office, by Bond’s lofty standards, and this put pressure on the next film, 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me. Broccoli, alone at the helm because of Saltzman’s departure, approached the young Steven Spielberg about the directing the next film, but Spielberg was wrapped up in pre-production on Jaws and wanted to finish that movie first. Desperate, Broccoli turned to Lewis Gilbert, who had previously directed You Only Live Twice. The screenplay was also in shambles, as Broccoli had commissioned a number of writers to work on it.

Fortunately, The Spy Who Loved Me was a rousing success. The opening scene culminated with Bond escaping his pursuers with an incredible stunt: he skied off a mountain and opened his parachute, which was the Union Jack. The scene drew huge applause in theaters when it was first shown, and the rest of the movie lived up to the lofty standards of this first scene. Critics praised the film’s exciting set-pieces and Moore’s performance, as it seemed that he had finally settled into the role and made it his own. Barbara Bach’s performance as the mysterious Soviet Anya Amasova was lauded, along with Curd Jurgens’ villainous term as the megalomaniacal Stromberg.

The Spy Who Loved Me’s closing credits promised that “James Bond will return in For Your Eyes Only,” but this would prove to be a false promise. For Your Eyes Only was intended to be the next film, but in 1977 Star Wars was released. Its huge success convinced Broccoli to make Moonraker the next Bond movie, because its premise offered the potential for some Star Wars-esque space battles. The script differed widely from Fleming’s original novel, favoring spectacle over realism. Indeed, Moonraker was not a hit with critics, who took issue with the absurd plot and ridiculous one-liners, but moviegoers loved it, and the film grossed $210 million at the worldwide box office, the most for a Bond movie at that time. It also was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

After Moonraker’s outlandish plot, Broccoli wanted to bring the franchise back to earth, both figuratively and literally. For Your Eyes Only used a combination of previously-rejected story elements and set-pieces from earlier screenplays to great success. The pre-credits sequence, in which Bond dispatches of a Blofeld-like villain, was written to give closure to the character of Blofeld from the previous films, although the filmmakers could not use Blofeld’s character (because of the aforementioned court case, Kevin McClory owned the rights to Blofeld so the movie could not name his character). Reviews were solid, and the film grossed $195 million at the worldwide box office.

After For Your Eyes Only opened, Moore’s contract expired. Broccoli began to look for a replacement, and James Brolin was a serious consideration. However, legal issues reared their ugly head again. McClory’s lawsuit against Ian Fleming had been settled out of court, and McClory was awarded a producer credit on Thunderball, and Eon Productions gave him the permission to produce a film based on the novel Thunderball after a ten-year period. After a long period of production issues, Never Say Never Again was scheduled to be released in 1983. McClory even got Connery to return, offering him a $3 million salary, a percentage of the profits, and creative control over the script and story.

Connery’s return was especially concerning for Broccoli. He was afraid that a new Bond would fail against the return of a fan-favorite. Moore agreed to re-up, and returned for his sixth film, Octopussy, which was released against Never Say Never Again in 1983. The film wasn’t considered anything special, a solid offering by Moore’s standards. Never Say Never Again was also considered average, although critics praised Connery for his performance. Octopussy actually ended up outperforming Never Say Never Again at the box office ($187 million to $160 million).

After Octopussy’s success, Moore decided to return to the role for his swan song: A View to a Kill. Moore, 57, was aging, and it showed. A View To A Kill was torn apart by critics, who went after Moore for his tired performance and the awkwardness of him shooting sex scenes with actresses twenty years younger than him. In subsequent interviews, Moore even admitted that he was far too old to be playing the part. Christopher Walken was serviceable as the villain, but the film was severely limited by Moore’s performance.

After A View To A Kill, Moore left for good. He was the oldest actor to have played Bond, starting at age 45 and ending at age 57. He portrayed Bond in seven films, and completely departed from the Bond of the Fleming novels. Some of his films have not aged well, but Moore’s performance fit the campy tone of his films perfectly, and he made the role his own. He accomplished the nearly impossible task of stepping out from Connery’s shadow, and he continued the franchise, which was in crisis when he stepped in the role.

With Moore’s departure, a number of actors were considered for the role of Bond. The three frontrunners were Pierce Brosnan, Sam Neill, and Timothy Dalton. Brosnan was initially approached to play the part, but he could not get out of his contractual obligations to the television show Remington Steele. Remington Steele, which aired on NBC, was not a particularly popular show at the time, but reports that Brosnan was being considered for the next Bond caused a spike in viewership, which caused the show’s producers to exercise on an extension on Brosnan’s contract. Neill was then considered, but Broccoli was not sold on him. The producers settled on Timothy Dalton, who had been approached after Diamonds are Forever was released to take over after Connery. Dalton, in his mid-twenties at the time, declined, saying that an older, more experienced actor should play Bond. Now, Dalton, an actor with a background in Shakespearean theater, jumped at the opportunity.

Dalton’s first offering came in 1987 with The Living Daylights. Dalton brought a much darker edge to Bond, and his performance was widely praised by critics. Fans also accepted him as the new Bond, and the film grossed $191 million at the worldwide box office, the franchise’s fourth most successful film to that date.

Unfortunately, Dalton’s luck ran out with his second and final offering, License to Kill. The film continued into the darker territory that Dalton had started delving into with the character. The story revolved around the gruesome maiming of Felix Leiter, Bond’s longtime ally, and his wife, and Bond’s subsequent quest for revenge. The film contained the most graphic violence in a Bond movie to date, and it was nearly rated R by the MPAA. However, the “PG-13” rating had just been established for films like Red Dawn and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, so the producers cut about thirty seconds of footage to obtain a PG-13 rating.

The production’s issues did not end there. The film’s original title was License Revoked, which caused confusion in America, where audiences thought that the title was referring to a driver’s license instead of a license to kill. The producers changed the name, but a lackluster advertising campaign did not help. Furthermore, the film was also opening in the summer of 1989 against such blockbusters as Lethal Weapon 2, Batman, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, which ironically starred Sean Connery in a leading role. The film succeeded at the worldwide box office, but only grossed a lowly $35 million in the United States.

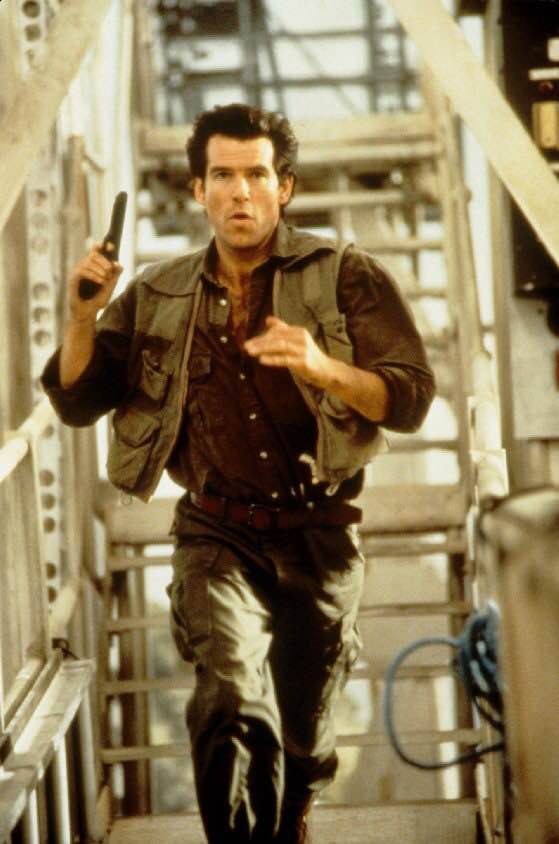

After a third film starring Dalton was planned for release in 1991, a dispute between the producers and MGM (which had become the parent company of United Artists) derailed the production. MGM was attempting to sell the rights to Bond, and Broccoli sued them. Eventually, the matter was settled and MGM kept the rights to distribution, but by that point, Dalton had lost interest in the role and announced that he was moving on. The producers turned to Brosnan after considering Mel Gibson and Liam Neeson, and he signed a three-film deal, with an option for a fourth, to play Bond. Brosnan accepted a relatively small salary at $1.2 million for Goldeneye.

The role of Bond wasn’t the only thing changing about the franchise, however. Albert R. Broccoli was in declining health (he would pass away a couple of months after Goldeneye), and the Cold War, an external factor that had played a role in so many Moore films, had ended. Bond had to modernize, and quickly. The franchise was in danger of fading into obscurity.

Goldeneye. (IMDB)

The producers took action to make sure that Goldeneye, which was released in 1995, was timely. They cast Judi Dench as M, the head of MI6, the first female actress to play M. They approached John Woo to direct, but he declined, so they settled on Martin Campbell, a previously unknown director who had never worked on a blockbuster like Bond before. Much like with Live and Let Die, the Bond franchise was in danger if Goldeneye was not successful. However, the film was a huge hit. Brosnan owned the part from the beginning, Sean Bean played a great villain, and the film blended humor, sex, and action in a seamless manner. A hugely successful video game accompanied the film, cementing its success. The film was the franchise’s most successful offering since Moonraker.

Trying to capitalize on Goldeneye’s success, the producers rushed the next film, Tomorrow Never Dies, into production. The script based the villain, a media elite played by Jonathan Pryce, off of Rupert Murdoch. The production started off without a finished script, and this harmed the entire film. Where Goldeneye felt fresh and inventive, Tomorrow Never Dies felt far too by-the-numbers Bond. Despite this, it was still successful at the box office, even though it opened against Titanic.

A new team of writers, Neil Purvis and Robert Wade, took over after Tomorrow Never Dies, and would write or co-write every subsequent Bond film, including Spectre. The producers wanted to get Bond back on a two-year schedule of production, so The World is Not Enough was released in 1999. Initially, Peter Jackson, the director of The Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogy, was approached, but the producers lost interest. Michael Apted, a relative unknown, was selected. The film received positive reviews, but the casting of Denise Richards as a nuclear scientist was met with derision. Still, the Bond franchise appeared to be in good hands, and Brosnan’s option was picked up for a fourth movie.

In 2002, Die Another Day was released, the twentieth film in the Bond canon. The entire film was essentially a tribute to Bond, as it contained references to every single preceding film. The film itself was a critical disaster. It made plenty of money, $432 million, but critics and fans alike tore the film apart for its overuse of CGI, ridiculous story, and overabundance of product placement. The theme song was also a trainwreck, worsened by Madonna’s extended cameo in the film. It seemed like the franchise had sold out.

After Die Another Day was so poorly received, the producers had to reconsider the direction of the franchise. In 2004, production on the next film, Casino Royale, began. Eon Productions had regained the rights to Casino Royale in 1999, when Sony Pictures swapped the rights to the book with MGM in return for the rights to the Spider Man franchise. Paul Haggis joined Robert Wade and Neal Purvis in writing a screenplay that produced a much more realistic story. The producers believed that Die Another Day had gone overboard with CGI, and the franchise had to be reeled in.

Casino Royale was planned with Brosnan in mind, but he was approaching the age of 50. He knew how maligned Moore was for playing the role past 50, so he decided to step down as Bond in 2004. The producers began the casting process, and actors like Henry Cavill and Sam Worthington were considered favorites for the role. However, both were considered to be too young, so the producers decided on Daniel Craig. The fan backlash to the decision was extreme: they protested that Craig’s blonde hair should have disqualified him from playing the part and that he was too bland an actor to play the suave and sophisticated Bond. The producers cast him because of his excellent turns in Layer Cake and Munich, giving them confidence that he could bring a fresh take to the character. And so, the production pushed on.

The film was met with almost universal acclaim. Critics praised Craig’s performance, noting that he seamlessly blended the suaveness of the character with a physicality that had not been seen before. The film was the fourth highest grossing movie of 2006, the highest grossing Bond film to that date, and ended up on several critics’ top-ten lists for the year. Eva Green’s performance as Vesper Lynd was also lauded, as she was one of the few Bond girls to actually feel like a fleshed out character instead of a sex object for Bond. The focus on practical effects went over well, particularly with a pulse-pounding opening foot chase between Bond and a bomb-maker.

The producers wanted to move quickly to capitalize on Casino Royale’s success. However, in 2007, the Writers Guild of America went on strike, leaving Quantum of Solace, the next film, without a finished script. Filming continued to move forward, and Craig and director Marc Forster were forced to rewrite dialogue on set during filming. The result was a slapped-together, rushed sequel to Casino Royale that was poorly received by critics. They especially went after Forster’s editing style, which favored jump cuts and shaky-cam over long, extended shots, which was far too reminiscent of the Bourne film series. Fans felt that Bond had lost his flair, and the films were beginning to descend into generic action film territory. The lack of Bond’s trademark gadgets and Q Branch didn’t help.

Skyfall. (IMDB)

Despite the poor reception, production began on Craig’s third film, Skyfall. External forces would soon intervene. MGM encountered financial trouble in 2010 and was forced to file for bankruptcy. The future of the Bond franchise was in jeopardy, and many began calling on MGM to sell the rights. Fortunately, the company was saved thanks to last minute litigation towards the end of 2010, and production resumed. The release date was set for 2012 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Bond franchise. Sam Mendes, who had made a name for himself with the Oscar-winning American Beauty, was selected to direct and Oscar winners Javier Bardem and Ralph Fiennes joined the cast.

Skyfall was a hit. It grossed more than $1 billion at the worldwide box office, the first Bond movie and only the fourteenth film overall to do so. Critics praised Craig, Bardem, and especially Judi Dench as M, who was given a much larger role in the film. Adele’s theme song also won an Oscar. The combination of her booming voice and piano made for the most popular Bond song since Duran Duran’s “A View to a Kill.”

Spectre, the franchise’s twenty-fourth movie, was pushed into production after Mendes agreed to return to the director’s chair (he was initially reluctant). The film was damaged by the Sony hack and negative press from Daniel Craig, who complained about the demands of the role. However, it is still poised to do fantastic business at the box office, even if the reviews haven’t been as glowing as Skyfall.

53 years and 24 films later, there is no other film franchise that can boast Bond’s longevity. The franchise has endured criticisms of misogyny, actors departing the role without warning (George Lazenby), box office successes and failures, rights disputes, bankruptcies, and a Madonna cameo. Skyfall’s huge success shows that audiences are as ready as ever to embrace Bond. The directors, actors, and writers will change, but Bond will be ever-present in pop culture lore. From the Aston Martin DB5, to the catchphrases, to the Vodka martinis, Bond has changed and inspired movie making throughout his existence.

Note: All box office statistics drawn from boxofficemojo.com. Other information drawn from imdb.com and wikipedia.org.

Cover image by cinestar.hu

Remember when the Voice used to have halfway decent features that actually had something to do with Georgetown?

https://georgetownvoice.com/2015/10/22/safe-spaces-or-echo-chambers/