“Lacks subtlety” is often thrown around in a derogatory fashion, used as a way to belittle or infantilize someone’s work. Chi-Raq, director Spike Lee’s new film, lacks subtlety. This, however, should not be taken as an insult. Instead, the film is not subtle because the conversations it sparks cannot be subtle any longer—just ask The New York Times.

The film lacks subtlety because guns lack subtlety. From the moment blood-red letters flash across the screen as the opening song plays, the audience knows it is receiving an overt message. “THIS IS AN EMERGENCY,” the letters read. A U.S. map appears, made up entirely of guns, and for the next two hours Lee’s moral remains clear: lay down your weapons.

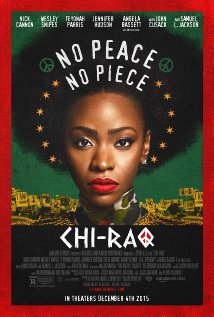

Chi-Raq, based on Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, takes place on the cruel streets of South Side, Chicago, with Teyonah Parris leading the way as Lysistrata. As the girlfriend of a local gang leader, who goes by Chi-raq (Nick Cannon), Lysistrata constantly sees firsthand the type of violence that terrifies and tears apart the neighborhood. She convinces the women of Chi-raq’s gang members, along with those of enemy leader Cyclops (Wesley Snipes), to withhold sex from their men until they can establish peace. Chaos ensues, as one might expect, but Lee takes said chaos in absurd and fascinating directions.

The content, style, and script of the film make it feel like a live event. The audience hears plenty of familiar names, ranging from Darren Wilson to Beyonce to Ben Carson, most of which tie closely into the story’s considerations of sex, gender, and violence. Even more notable is the play-like presentation of the film. At several key moments, Samuel L. Jackson’s Dolmedes addresses the audience directly, acting as a sort of one-man Greek chorus, framing the story as one that unfolds before our eyes rather than one that was staged, filmed, and produced at great lengths.

The screenplay, written by Lee and Kevin Willmott, bounces and rhymes its way in and out of scenes, intentionally creating incongruencies between the silliness of its wit and the weight of its subject matter. One is left wondering at times if the lyrical cleverness of the script distracts from the matters at hand, but most of the film’s bizarre moments and lines seem intentional, shocking but still driving forces towards the clear and direct statements of the narrative’s final moments. The rhymes make certain moments feel like slam poetry sessions, which may not be far from what Lee and Willmott intended, given the assertiveness achieved in that sort of setting.

No one individual performance dominates the film, though Parris’ turn as Lysistrata is powerful enough to provide the film with a sturdy foundation around which the rest of the strange cast of characters gyrates and spasms. Dolmedes is detached from the events taking place, but Jackson still manages to be one of the film’s highlights. John Cusack, Angela Bassett, and Jennifer Hudson stand out in supporting roles of various magnitudes; Father Mike Corridan (Cusack) provides perhaps the most memorable scene, an enraged sermon regarding America’s gun crisis following the shooting death of a young girl on a nearby street. Several familiar faces appear in brief, including Dave Chappelle and Isiah Whitlock, Jr. (The Wire). These cameos range from entertaining to uproarious, comic relief of sorts, to stay in line with the Greek line of thinking. There are no weaknesses in the cast, but the strength of the movie lies beyond them, in their numbers, and in the cause for which they come together.

Chi-Raq has already generated a bevy of critiques and controversies, with many questioning its effectiveness as a “message film” and some Chicago citizens accusing Lee of exploiting those struggling in their city for his own personal gain. Notably, Chance the Rapper, who hails from Chicago, spoke out against the film, calling it “offensive” and “problematic.” Looking closer at his complaints, however, reveals a misunderstanding that seems to be driving many of the negative reactions to Lee’s production. Chance tweeted, “…the idea that women abstaining from sex would stop murders is offensive.” One can see his point, but having seen the movie, it now seems like a gross misinterpretation of what Lee set out to accomplish. Some people mock “the sex strike myth,” but the movie shows no intentions of presenting its strike as a true solution.

Instead, the strike devolves into absurdity and bizarre antics as the story progresses. Eventually the movement gains traction, but it is not what brings about the type of lasting peace Lee, his characters, or our nation at large desire. The sex strike grabs attention and exposes the frailty of masculinity and its needs that seem to lie at the core of gang violence and insanely stubborn gun-lust. In a way, the sex strike mirrors the film itself, in that each sets out to shake people out of apathy through dramatic expressions of frustration. Lee might think there’s some merit to sex striking, but his film does not point to it as a sufficient means to a peaceful end. That comes from a deeper recognition of the absurdity of our nation’s gun crisis (or obsession, or love affair, or disorder), the crisis that has left it—as Cusack’s Corridan says—easier to purchase deadly weapons than computers.

In one scene, Lysistrata and a friend discuss the South Side way of life. Regarding the constant danger and violence, her friend says, “It’s how we live.” Lysistrata, exasperated by this line of thinking so deeply entrenched, answers, “It’s how we die.” Their words refer to the warfare of real-life “Chi-Raq”, but they resonate with every American, or at least with every American capable of seeing just how profoundly shameful our gun crisis has become. In the movie world, this is the season for nuance, in which directors and films and performers state their case to lift any of the countless shiny trophies that will be presented in the coming weeks and months. We will hear of films (that no one sees) or performances that are “subtle” or “understated,” and Chi-Raq will not be one of them. Because it should not be subtle or understated. Because it should be loud and blatant and overbearing. Because people need to wake up, and Lee has rung the alarm, loud and clear.