“Today it is the duty of a genius to remain unrecognized.” –The Physicists, Friedrich Durrenmatt

The Physicists is a very short play by Swiss dramatist Friedrich Durrenmatt that takes place in the drawing room of a sanatorium for the privileged and wealthy of Europe. Dr. Mathilde von Zahud is the chief psychiatrist and owner of Les Cerisiers. Her most interesting patients are three physicists who are very confused about their identities. The first is Herbert Georg Beutler, Isaac Newton, or Jaspar Kilton. The second is Ernst Heinrich Ernesti, Albert Einstein, or Joseph Eisler. The third is either Johann Wilhelm Mobius, whom King Solomon regularly visits in order to dictate new psalms and pass on knowledge of the “System of All Possible Inventions”, or he is Solomon himself.

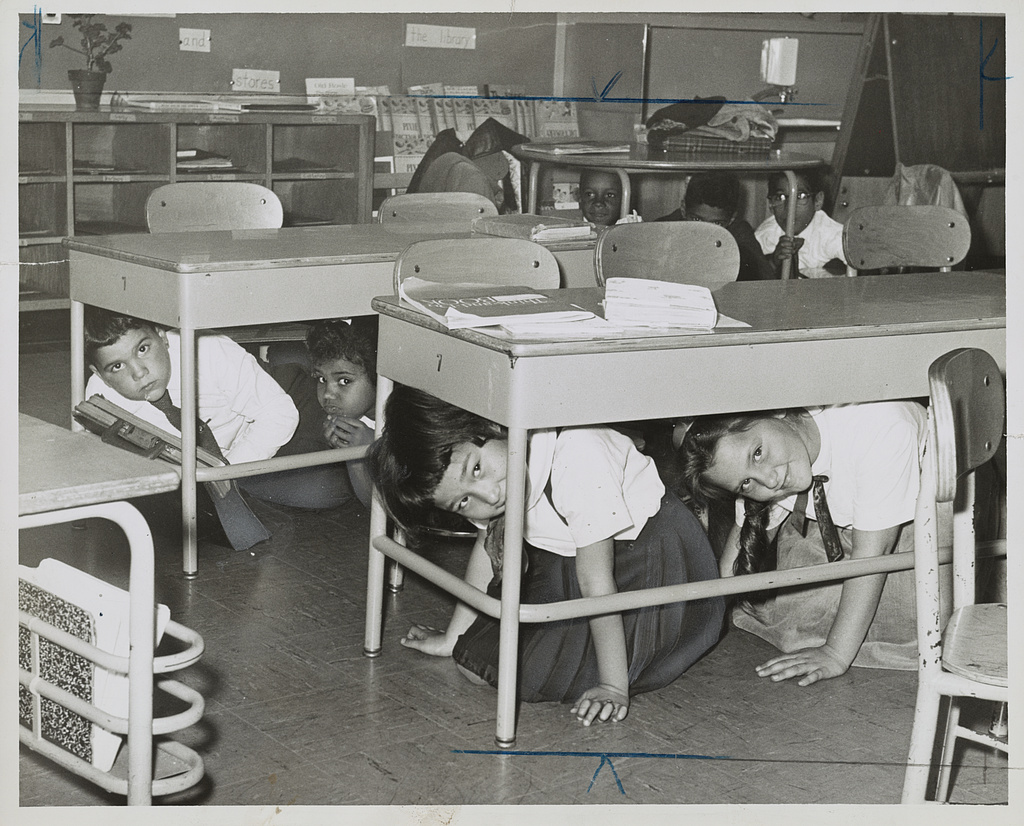

Swiss dramatist Friedrich Durrenmatt wrote The Physicists in the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. The invention of nuclear weapons would lead to the Cuban Missile Crisis months after the play was written, and was more generally a substantial source of anxiety for most people. Resounding themes of the responsibility of scientific discovery and the pursuit of knowledge are salted with the dark humor of insanity and absurdity to create a delightfully entertaining two-act play that confuses as much as it amuses. The more serious undertones, especially in light of the fragile politics of that era, are dismissible if one simply chooses to enjoy the play as light literature, but they are in fact quite fascinating to consider in our current generation of breathtaking technological innovation and medical progress.

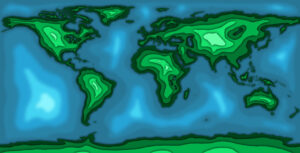

There has never been a time period in history when rapid change has been so possible and so easy. Globalization and the invention of the internet has made it so that communication with individuals and organizations around the world is possible at the click of a button, resulting in an incredibly refocused and diversified scientific and intellectual community. The great minds of our generation are able to do research in unparalleled facilities with unthinkable tools and communicate findings to each other, making the elusive tendrils of knowledge and creation seem more attainable than ever.

In a time where every new discovery or invention has almost no limits on the communities and countries it can reach, the consequences of naively pursuing knowledge have never been so serious. In the consideration of links between science and morality, we must push first for a clear idea of what it means to pursue knowledge.

This pursuit is one of the few (especially with the scientific perspective of human-animal traits today) uniquely human traits. Trying to understand the world around us in a deep and meaningful way is what sets us apart from all other life on Earth. There are fascinating observations to be made about the relationship between knowledge and nature in both its Judeo-Christian presentation and in a contemporary consideration, where we easily see knowledge as what has allowed us to manipulate, change, and even destroy nature. From harmless paperclips, to massive deforestation, to bottles of insulin, to the atom bomb, everything we create as a result of scientific pursuits has the potential to tip the balance of nature. Besides its substantial impacts on the natural world, this pursuit also has the potential to tip the balance of human society. Scientific and intellectual projects are most frequently focused within a particular community, often encouraged by the state, resulting in new knowledge lacking global coherence. This factor is what opens the possibility of using the invention against another group, or of using it to improve the lives of only a select group of people. With the idea of ‘us’ against ‘them’ developed, the pursuit of knowledge becomes a power struggle between nations and communities. Europeans used gunpowder to further their imperialist interests, the U.S used atomic bombs to end WWII early, the list goes on. This is the mentality that led to the arms race and the terrifying possibility of mutually assured destruction.

So who is responsible for what results from seemingly harmless inquiries? Scientific discovery and the pursuit of knowledge is a twofold process: understanding and creation (or innovation). Sometimes both occur simultaneously, while sometimes one occurs without the other, but the point is that scientists rarely know what they are getting into when they begin to explore a concept or experiment on nature. The inconsistency of the process makes it almost impossible to predict all possible implications and consequences. Whether it is the scientist or humanity’s responsibility, if we are able to take all of humanity into account when considering who is impacted by the process of discovery, instead of just our immediate religious, cultural, or national group, catastrophic consequences are much easier to avoid.

As obvious as this conclusion seems to be, the problem is putting it into practice. With several political leaders and campaigns today focused on fear-mongering, people are incited to view themselves one dimensionally and to cling tightly to only one facet of their identity. This necessarily results in the exclusion and othering that make whatever knowledge and tools we do have all the more dangerous for those we do not consider to be a part of ‘us’. As easily as science can be the cause and the perpetuating force of human annihilation, it can also be harnessed to better understand both what we study and the consequences of studying. In the face of climate change and weapons of mass destruction, the pursuit of knowledge becomes our last hope for both peace on Earth and peace of mind.