Tabling for three hours for the undergraduate Japanese club at the student activities fair a few weekends ago made me realize why diversity education is so important to the studies of a Georgetown undergraduate.

“Oh, it’s just another cultural club,” remarked one student before she walked away, perhaps in search of a written application that she wished to masochistically fill out. “How Japanese is Japan Network? Like, are there any Japanese people in J-NET?” another asked with the most puzzled look.

Of course no group at Georgetown should define itself by ethnic homogeneity and cultural purity, intentionally or not. Nonetheless, after abruptly transplanting your life thousands of miles away from home, for an international student, it is refreshing gravitate towards a group who can speak Cantonese and appreciate roasted pork belly in a place of pumpkin spice lattes, graduation rings, and semi-underground fraternities. In my freshman year, I became an active ambassador of my own culture, hanging scrolls outside my door to celebrate Chinese New Year, and making my Darnall floormates eat mooncakes. I still remember quite fondly how one of my friends spat out the salty egg yolk in disgust.

Is it possible to become too aggressive at cultural ambassadorship? Two years ago, I made fun of Leo’s for writing “Got a yen for great food?” in their marketing campaign for Chinese New Year on Facebook. In emotional and perhaps inebriated conversations with friends, I have lamented the one too many times strangers and acquaintances have expressed puzzlement at the accent, or lack thereof, that accompanies my English speech.

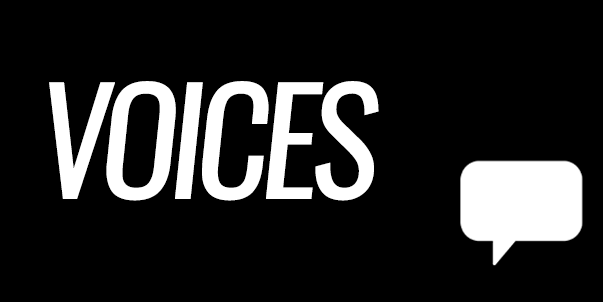

I am beginning to wonder if these moments of hypersensitive frustration would impede interpersonal connections. Take, for example, the seemingly innocuous question of “Where are you from?” That question threatens to unilaterally place people in distinct categories that they do not fit. In today’s political environment, some might interpret my previous sentence as a manifestation of political correctness—anyone who asks that question deserves to be attacked, so it is better not to ask that question—and thus a limit on free speech. After all, no one wants to be called out as racist. But this fear of being attacked prevents us from intellectually engaging with the problem of difference beyond the cursory. A person who would have considered how some people find multiple, overlapping identities from, for example, the lottery of birth or the privilege of education would ask a better question like, “What’s your story?”

On the other side of the spectrum, I also wonder whether it is possible to explore too deep into a culture that I do not originally belong in. During my semester abroad in Tokyo, many times when I met someone, he or she couldn’t stop talking about how much more ‘local’ my Japanese was than they might have expected, meaning I didn’t sound like a language textbook. It was as if the maximum potential that all Japanese language learners could muster was supposed to be “konnichiwa” (hello) and “arigatou” (thank you), and no more.

The more cultural sensitivity I tried to acquire in Tokyo, the further I threatened the neatly defined identities and stereotypes that mainstream Japanese society had reserved for foreigners. Consequently, I confused anybody who tried to objectify me as a foreigner. I could speak English and lived in America, but I was neither white nor American; I was not Japanese, but I spoke more Japanese than the average exchange student; I told people I was Chinese; but I hardly spoke in Mandarin with anyone nor did I live in mainland China.

At the last day of my part-time job at the convenience store in Tokyo, the customer in front of me, noticing my lack of Japanese ethnicity, turned to my Japanese colleague to remark about my Japanese accent. He then faced me to ask, in English, the question that fascinates so many: “Where are you from?”

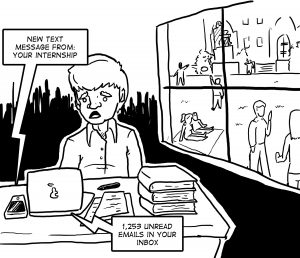

Two weeks ago, the descendants of the 272 slaves sold for Georgetown’s financial benefit stood in Gaston Hall, responding to the university’s offer to apologize and reconcile for its historical sins. I gave up on joining the long line to enter the press event, and resigned myself to worrying about my precarious postgraduate life on my laptop in the Healey Family Student Center. But a staff member decided to put a livestream of the press event on the big screen, and a small crowd, including me, found themselves gravitating towards it, silently reflecting on the unforgettable, perhaps unforgivable, crime that our school once committed based on difference.

It is always painful to confront the injustices stemming from difference. That pain lies not only in the heated news headlines when students rally for Aramark workers at Leo’s or for #gu272, but also in the most sacred, intimate details of our own lives: whether I’m jeopardizing my relationships with family and friends when I come out to them as bisexual, or whether I can get through another session of CAB Fair for Japan Network without someone questioning the integrity of my membership in the club of which I love to be a part.

This challenge of difference will be the defining question of our lifetime. Not necessarily because the answers have gotten easier, but because it is getting harder not to ask those uncomfortable questions. I know that once I succumb to the responsibilities of adulthood after I graduate, I realistically will have less freedom to let these questions shape me into a better person. I hope to treasure my time at Georgetown that I spent letting the challenge of difference educate me, and I hope you do too.