The women — corpulent, naked, and defiantly at ease — gyrate in slow-motion to haunting strings from composer Abel Korzeniowski, waving sparklers as the opening credits for Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals roll. The scene functions as both a meditative microcosm and an eye-catching hook: a promise of more things beautiful and strangely evocative to come. The film, fashion designer Ford’s second foray as a director, producer, and screenwriter after his 2009 Oscar-nominated film A Single Man, follows three narratives detailing present, past, and fiction set in Los Angeles, New York, and West Texas, respectively. Simultaneously gorgeous and brutal, structurally intricate and artistically composed, Ford’s signature aesthetics-driven vision along with an impressive collection of well-cast A-listers elevate Animals from dispassionate sophistication to sleek, atmospheric thrills.

In the film’s first minutes, we discover that the women from the opening montage are part of an art installation curated by Susan, a successful yet restless L.A. gallerist played by Amy Adams. Her well-tanned husband (Armie Hammer) is perpetually off on business and her daughter is grown, leaving Susan alone in her expansive mahogany house to brood out her floor-to-ceiling windows and stew in her outdoor hot tub. Though they have not spoken in 19 years, Susan’s writer ex-husband Edward (Jake Gyllenhaal) sends her a manuscript for his dark new novel called Nocturnal Animals, a term he used to describe her when they were a young couple in New York. The book chronicles the horrific consequences of the fictional Hasting family’s nighttime road trip through West Texas, an effectively jarring answer to the controlled emotion of the film’s reality. Ford reveals the novel’s plot in excruciating phases, mirroring Susan’s reading of it in the film’s present as she reflects back on her relationship with Edward.

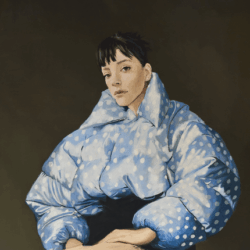

In tandem with cinematographer Seamus McGarvey and editor Joan Sobel, Ford differentiates storylines through color — cool blues for Susan’s present and yellowed tints for the revenge plot — and splices similarly-framed shots to further unite reality and invention, sustaining a tone of simmering dread. Fittingly, each frame of the film would not be out of place in an art gallery display. Whether it is L.A.’s snake-like freeways or two naked corpses on a red couch, Ford’s meticulous attention to composition imbues every shot with majesty and intent.

Draped in opulent jewel tones and chunky earrings, Adams smolders as a woman whose seemingly-flawless life belies a painful past. Ford need only cut to a close up of her grave, pensive eyes — and he does so often — to convey a lifetime of regret. There are no exaggerated gasps or sudden bursts of tears; as Susan, Adams gives a masterclass in repressed guilt and fear. Her eyes flicker; her mouth quivers; she presses her hands to her face. Adams’ performance as young Susan — an ambitious twenty-something getting her master’s at Columbia — is just as nuanced. She gets only a few scenes to act out Susan’s journey from idealistic young lover to disillusioned wife to cruel betrayer, and makes the transition deftly, emanating a quiet melancholy throughout. Laura Linney (and her outrageously sculpted hair) makes a brief appearance and crackles with haughty condescension as Susan’s icy mother. With only a watery glance, however, Adams steals the scene right back.

With a Texas twang and hollowed cheekbones, Gyllenhaal does double-duty as Edward and Tony Hastings, the fictional father in Edward’s book. Edward is the romantic to Susan’s pragmatist, the emotion to her realism and, while Gyllenhaal acts with intense humanity, Adams benefits from a more multi-faceted and engaging character. Fortunately for us, Edward’s book exposes his inner machinations and Gyllenhaal gets a storyline all to himself in the form of Tony. As the tortured man on an interminable hunt for the men who brutalized his wife (Isla Fisher) and daughter (Ellie Bamber), he delivers a desperate and provocative performance. His grief and compulsive rage are palpable as he teams up with a reticent cop (Michael Shannon) and faces off against a terrifyingly unhinged ringleader (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). Although his is a story within a story, Tony’s tragic arc shocks and captivates despite its roots in fiction.

Animals is a mood. It is Adams’ protective sheath of red hair, Gyllenhaal’s white-knuckles, and Taylor-Johnson’s menacingly greasy split-ends. It is Korzeniowski’s pulsing score, a well-placed fade-in, and the oppressive darkness that colors a majority of the film. The film speaks through its tone and visuals and ends like it begins: with a sudden, emotive cut. There is no resolution, no closure, and certainly no happy ending. Just like that, we are left alone to ponder the cruelty that lurks beneath the stylish and the glamorous, the horror and the beauty of our world.