Meghan Bodette (SFS ‘20) had been up all night. For the last three days, she had attended protests, marching, chanting, and showing no signs of slowing down. Bodette, along with many other Georgetown students, walked to the Supreme Court despite the 30 degree weather one late evening in January. They were going to be heard.

President Trump’s Jan. 27 executive order stopped travel from seven Muslim-majority countries: Iraq, Iran, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Somalia, and Libya. Under the terms of the ban, citizens of these countries cannot enter the United States for 90 days, with few exceptions. The mandate also halted all refugee acceptance for 120 days and indefinitely banned refugees from Syria. The executive order stated that the U.S. would give preferential immigration treatment to Christian refugees.

The order was a worrying development for many in the Georgetown community, like Sonali Dhawan (COL’18) who spent a semester studying abroad in Jordan. “I feel that it is a death warrant for refugees all across the world and specifically these countries,” said Dhawan. “When I was in Jordan last fall, I worked with and did research on Syrian-Palestinian refugees and saw firsthand the trauma of displacement.”

The order was a worrying development for many in the Georgetown community, like Sonali Dhawan (COL’18) who spent a semester studying abroad in Jordan. “I feel that it is a death warrant for refugees all across the world and specifically these countries,” said Dhawan. “When I was in Jordan last fall, I worked with and did research on Syrian-Palestinian refugees and saw firsthand the trauma of displacement.”

According to university spokesperson Rachel Pugh, the ban directly affects several students at Georgetown. In an email to the Voice, Pugh wrote that the university identified 20 students across its main, law, and medical campuses who would not be allowed to re-enter the United States if they traveled outside the country under the terms of the ban if it were to be reinstated. She added that none of these 20 students were currently abroad.

Pugh also commented that Georgetown was communicating with students directly affected by the executive order. “As recently as last Friday, senior Georgetown leaders met with undocumented students and members of Georgetown’s Muslim community,” Pugh wrote. She said the university is closely monitoring any new developments.

Other students and faculty also know individuals affected by the ban. Bodette works at a non-profit that works with refugees in Kurdistan, and many of her colleagues have been directly impacted. “I know a few [colleagues] who are now having to decide between staying here and going to visit family and potentially not being able to come back into the United States,” said Bodette.“I don’t think that is a decision that anyone should have to make.”

History professor Ananya Chakravarti said the ban was especially jarring given her own immigration status. Originally from India, she recently received her green card, and many of her friends are green card holders from the affected countries who were originally targeted by the ban. “A friend of mine is a Syrian refugee who is a green card holder and his brother is currently abroad and very likely is going to have serious trouble coming back into this country,” said Chakravarti. “So it just felt personal.”

Chakravarti also expressed concerns from an academic standpoint, particularly in the field of history. Because Iran has reciprocated with a ban on U.S. passport holders, Chakravarti worried that historians would not be able to access archives that they needed for their research. She also discussed calls within the international community to boycott academic conferences in the United States, which she worried would disrupt the exchange of ideas and isolate U.S. academics.

Chakravarti also expressed concerns from an academic standpoint, particularly in the field of history. Because Iran has reciprocated with a ban on U.S. passport holders, Chakravarti worried that historians would not be able to access archives that they needed for their research. She also discussed calls within the international community to boycott academic conferences in the United States, which she worried would disrupt the exchange of ideas and isolate U.S. academics.

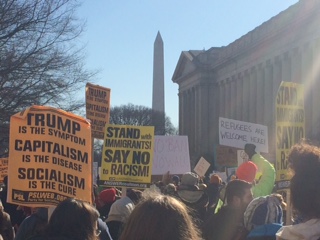

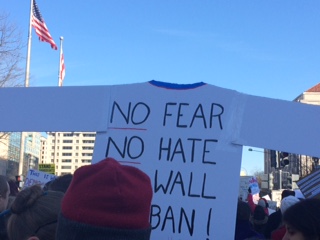

Those disturbed by the executive order channeled their discontent through protests throughout Washington, D.C. over the last few weeks, and many Georgetown students participated. At airports, monuments, and government buildings, protesters held signs and chanted “No ban, no wall” and “No hate, no fear, refugees are welcome here.”

Angela Maske (NHS ’19) attended the largest of these protests, a gathering outside the White House on Jan. 29, and noted the importance of participation in protests. “It’s especially meaningful to put your body in a space where you are representing resistance,,” Maske said. Dhawan also praised the disturbance many of the protests were causing with marches blocking off streets and impeding traffic, and she called President Trump’s actions so dangerous that causing disruption is necessary to have the protesters’ message heard.

Bodette expressed a similar feeling, saying that as a white, Christian woman, she was in a position to help others and felt compelled to take advantage of it. “I need to use [my] privilege to speak up for people who are less safe, who are less secure, and who this administration is targeting,” Bodette said.

Despite the protesters’ deep concerns, both Maske and Chakravarti discussed the sense of community they felt at the protests, describing people having conversations with strangers, helping each other up onto walls, and exchanging words of encouragement.

Chakravarti attended the White House protest with faculty members of Georgetown’s history department, and said the experience was heartening. “We are at an institution where many of us recognize the dangers of what is happening and many of us are willing to counter them,” Chakravarti said.

Caitlyn Cobb

Dhawan said that she protested for a variety of reasons including seeing the strength of the opposition to Trump’s policies and the ability to surround herself with people who hold similar stances to herself. She added another benefit of protesting: the ability to call the attention of the public, as well as legislators, to these issues.

In addition to the public protests throughout D.C., university students also held a candlelit vigil called “Hoyas for Justice” in Red Square on Feb. 1. Students gathered to pray and listen to speeches about the effects of the executive order.

Georgetown also responded to the ban on an administrative level. On Jan. 29, President DeGioia sent an email to the student body recommitting the university to championing the international students. “Our international character is integral to our identity as a University, to the free exchange of ideas, and to our ability to support all of our students, staff, and faculty in contributing to our global community,” DeGioia wrote.

In his email, DeGioia also discussed how Georgetown’s Jesuit values press the university to embrace its Muslim population, which Chakravarti said she was grateful for. “I feel extremely lucky to work in an institution that espouses Jesuit values of inclusion and of compassion and President DeGioia has come out very strongly from the moment after the election to reaffirm Georgetown’s commitment to these values.” Other groups on campus, such as GUSA and the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies (CCAS), have released their own statements affirming their support of students affected by the ban, with CCAS condemning the ban as well.

However, some students have said these actions are insufficient and hope the university will take additional steps to protect non-citizen students, faculty, and staff. Several universities, such as Princeton, Dartmouth, and Rice, have explicitly opposed the ban, and Dhawan said Georgetown should take further actions to protect its students. She cited Columbia and the University of Michigan as universities that have taken steps towards declaring themselves sanctuary campuses—schools which do not release the immigration status or other personal information of their students—and said she hoped Georgetown would follow suit.

Caitlyn Cobb

In addition to their statement, CCAS held an emergency town hall on Feb. 2 to respond further to the ban. Various attorneys, advocates, and lobbyists connected to Arab-American relations discussed the implication of the ban as well as the steps people affected could take in order to keep themselves safe, such as avoiding unnecessary international travel, using state-issued identification, such as a driver’s license, rather than foreign passports when traveling within the United States, and not disclosing information to immigration officials or signing forms without consulting an attorney.

Chakravarti mentioned initiatives that she was discussing with colleagues in the history department, such as taking advantage of being in close proximity to the American Historical Association to set up a meeting to discuss alternate, more accessible locations for their national conference. Faculty members were also considering keeping positions open for students and staff who might be accepted but would be unable to come to the United States to study or work because of the ban. For example, if an individual was hired to begin education or employment at a certain date, that date could be delayed indefinitely if they were having problems immigrating.

Activists like Dhawan stressed the necessity of taking action outside of attending protests, noting the importance of a steady resistance through petitioning, calling members of Congress, and supporting organizations involved in fighting discriminatory policies. “It has to be a continuous effort,” Dhawan said.

Chakravarti echoed Dhawan’s statement, calling on her experience as a historian to warn against complacency. “I think the important thing is not to sit back and believe that this is somehow normal,” said Chakravarti. “The danger is if we normalize this.”