As the Voice nears our 50th anniversary in March 2019, we are looking back at our history, alumni, and life after the Voice.

In the fall of 1967, Georgetown was on the cusp of a seismic social shift. When he arrived on campus, Martin Yant (SFS ’71) found a stodgy, buttoned-up men’s club where a blazer and tie was the de facto student uniform. The College would not admit women for another two years. But a wave of civil unrest soon swept the country as tensions over war and race mounted, changing campus culture forever.

“Georgetown was pretty conservative and insulated, and that changed greatly because of the assassinations in the spring,” Yant said. After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968 and the ensuing riots, Yant said he remembers “standing up on Loyola Hall, on the roof, watching the city burn.”

Sen. Robert Kennedy was assassinated two months later, accelerating the formation of an anti-war, anti-establishment counterculture among Georgetown students. “It was an amazing transformation in a very short period of time,” Yant said.

When he returned to campus in the fall of 1968 for his sophomore year, that stuffy culture from his first year was notably absent. “All of the sudden when people came back in the fall of ’68, everyone was wearing blue jeans, had long hair, and no coats and ties, for the most part,” he said.

Yet campus media did not reflect that change. Yant said The Hoya eschewed coverage of anti-war demonstrations and the shifting culture, holding onto its traditionally socially-conservative foundation of the time. “[The editor] just felt that the purpose of a campus newspaper is to cover the campus, and he had no use for the anti-war movement, which had become a major part of campus activity,” Yant said. “It was everywhere, and he just wanted to ignore it.”

In the spring, several students broke away from The Hoya to form The Georgetown Voice, a magazine in which they aimed to report and reflect on the emergent student counterculture.

Initially, Yant was primarily focused on politics and only casually interested in journalism. He was a self-billed “progressive Republican,” though he said he was quickly alienated from the College Republicans, and the party itself, by a student whom he described as particularly obnoxious, named Paul Manafort (MSB ’71, LAW ’74).

Yant was peripherally involved in the Voice at its inception in the spring, focusing instead on his two jobs, but became more active in the fall. For his first story, he attended a protest against a proposed bridge that would cross the Potomac into Georgetown, potentially destroying several thousand homes. Police eventually told the protestors they were to disperse or be arrested.

“Not too many people dispersed,” Yant said. He was accosted by a police officer. “He grabbed my pen and notepad, threw it down, and said, ‘You’re under arrest.’” Yant and 86 other Georgetown students were arrested that day.

The story turned into a first-person narrative of his experience inside the jail, which won an Edward B. Bunn award, a university award for journalistic excellence. “That really got me interested in journalism,” he said.

The survival of the publication, however, was quickly jeopardized. The director for student activities, Robert Dixon, who personally allocated funds to the Voice, was indicted for embezzling from the student activities fund, casting doubt on the its future funding. Furthermore, some speculated that the Voice was founded largely as an effort to bolster a friend’s campaign for GUSA president, whose success possibly rendered the magazine obsolete to the founders.

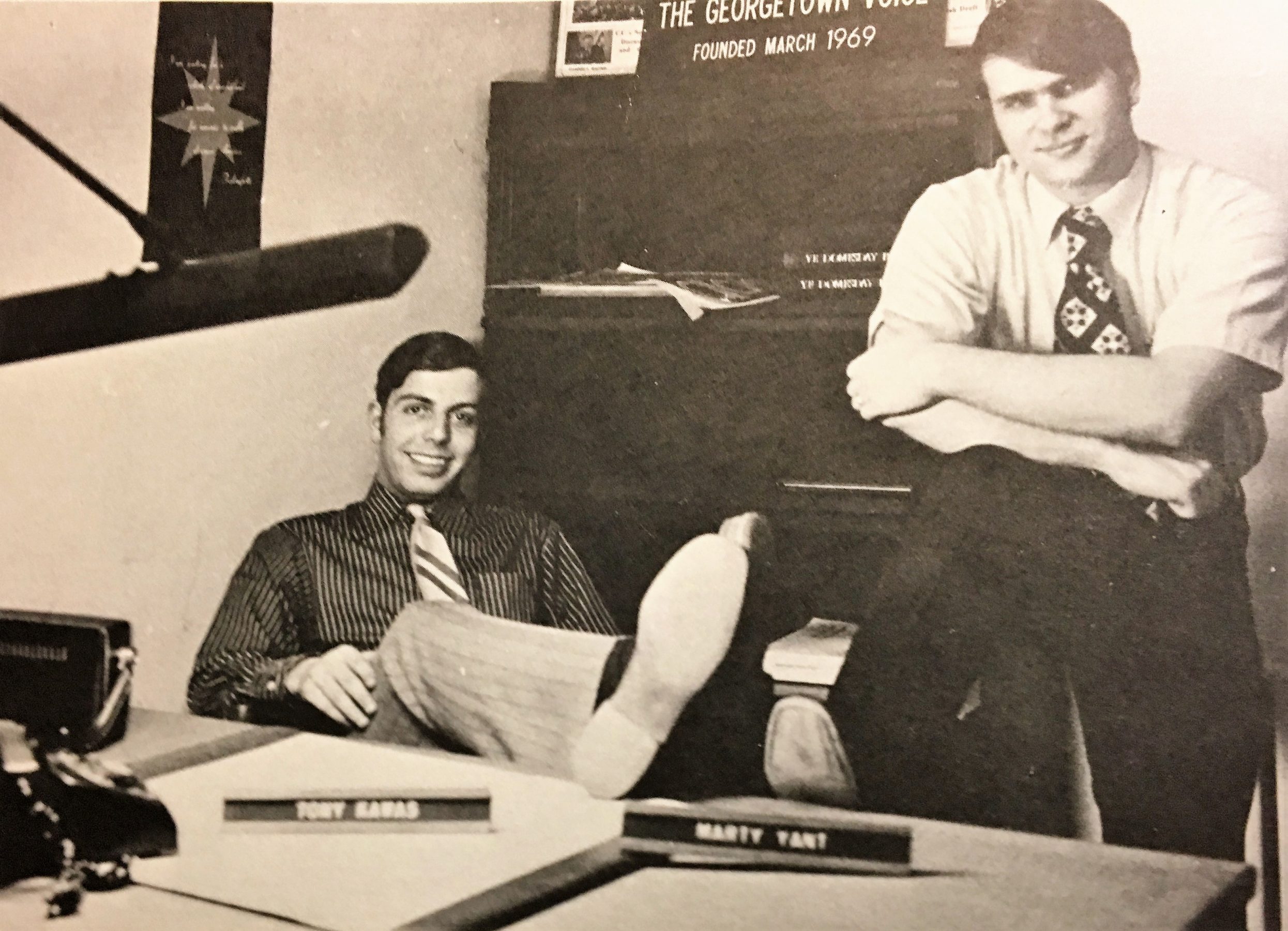

Yant spearheaded an effort with several other students to resuscitate the Voice. He took on the role of managing editor and recruited a prominent campus conservative, Rick Newcombe (COL ’72), who now runs a media syndicate, to write a column in an effort to give the publication a more bipartisan, mature tone.

Still, the Voice maintained its countercultural slant. Yant remembered one illustration on the back cover of an issue in particular: a raised red fist to demonstrate solidarity with the student strikes of 1970 against the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia.

After graduation, Yant worked as a reporter at the Pittsburgh Press and the Chicago Sun-Times for several years before landing a position as editor in chief of the News Journal in Mansfield, Ohio, at 28. “I considered it a dream come true that turned into a nightmare,” he said.

Mansfield, Yant discovered, was a hotbed of government corruption. “My first day on the job, someone called me and said, ‘Are you going to cover up all the dirt in Mansfield like all the other editors have?’” Yant said.

What began as an investigation into the plight of a truck driver buried in a blizzard opened the door on a plethora of abuse at the local sheriff’s department. “The torture, beatings, corruption that was going on was just unbelievable,” Yant said. His reporting eventually led to the conviction of the county sheriff and seven deputies on various charges of corruption and assault.

When he discovered that his publisher was entangled in the same corruption he was investigating, Yant set out to create his own daily newspaper. “I had a big following at that point,” he said. He started The Ohio Observer in 1978 to continue probing into the city’s corruption, investigating cases from a crooked coroner to an illicit pornography distribution ring run by singer-comedian Sammy Davis Jr. in Mansfield.

Yant’s investigations at the Observer provoked strong backlash from organized crime rings, at one point turning violent—Yant was forced to shutter the paper after just one year after his circulation office was firebombed. “A lot of our advertisers were getting threats, so just out of fear, nobody would advertise with the paper anymore,” he said.

After the bombing, he moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he worked as a columnist at The Columbus Dispatch and became interested in wrongful convictions. After spats with his editor over criminal justice issues, he became a licensed private investigator, opening his own agency aimed at exonerating wrongly convicted individuals. Since then, Yant has published four books, including two on the corruption he uncovered in Ohio.

He has also helped free 20 wrongly convicted individuals, including two who were sentenced to death. Currently, Yant is working to exonerate four men in Huntington, West Virginia, whom he believes were wrongly convicted more than a decade ago for the murder of a woman. In partnership with several criminal justice groups, Yant believes he has uncovered DNA evidence implicating a man in Ohio for the murder.

Yant credits the Voice as the basis for the path his career is taking even now, years after he graduated from Georgetown. “The Voice was the most valuable part of my fantastic Georgetown experience. It set me off on a highly fulfilling journey as a journalist, author, and investigator,” he said.

“I couldn’t have asked for more.”

Thank you for this story. I was with the Vouce from 1977-1981. I readily agree that the Voice offered many of us the opportunity to leap into the unknown to explore and make sense of what was in our hearts.