Note: Spoilers for The Kitchen ahead.

I arrived at my local AMC one August afternoon feeling skeptical. I was about to watch Melissa McCarthy in a serious role, and I wasn’t sure if it could live up to Megan in Bridesmaids or Sookie in Gilmore Girls. In The Kitchen McCarthy, along with Tiffany Haddish and Elisabeth Moss, play a trio of Irish mobsters’ wives who decide to run the mob themselves when their husbands end up in jail.

I left the same way I entered—skeptical—but for a different reason altogether. The movie was entertaining enough; that wasn’t the problem. And at first glance, the message seems empowering. The three main characters learn to be strong women, independent of the men around them and unconstrained by their “proper” role in society. With so many films failing to even pass the Bechdel Test, which measures a film’s representation of women, it was nice to see three complex women at this movie’s center, especially when most other films in the mobster category are about men.

What bothered me was what the movie considered “strong.” As the main characters gain more control over the mob, they become increasingly tough and hardened. They begin to kill not out of necessity but because their newfound strength means they can: Tiffany Haddish’s character pushes her aging mother-in-law down the stairs, and Melissa McCarthy’s character has her husband killed solely for her own gratification. The movie presents their character arcs as clear positive development. They’ve finally learned to assert themselves and abandon society’s expectations—or, have they just moved from projecting one sexist trope to another?

Despite the growing amount of strong female characters in movies, the way pop culture represents strength itself remains monolithic: it’s the stereotypical masculine man, who is tough, stoic, aggressive, and definitely has abs. Tom Cruise in the Mission Impossible movies. Matt Damon as Jason Bourne. These characters don’t display emotion like the stereotypically feminine woman, and they crave combat to prove themselves, unlike their submissive female counterparts. This portrayal of strength, even by a woman, doesn’t help anyone: it certainly doesn’t help women who are seen as weak for not adhering to this ideal, but it also puts unnecessary pressure on men to conform to an emotionless, macho standard in order to be “real” men.

When pop culture tries to present strong women, therefore, it transplants this definition of strength. So actually, the women of The Kitchen still meet society’s expectations, except this time they are society’s expectations of masculinity. The movie tries to uplift women, yet it ends up teaching us that femininity is weak.

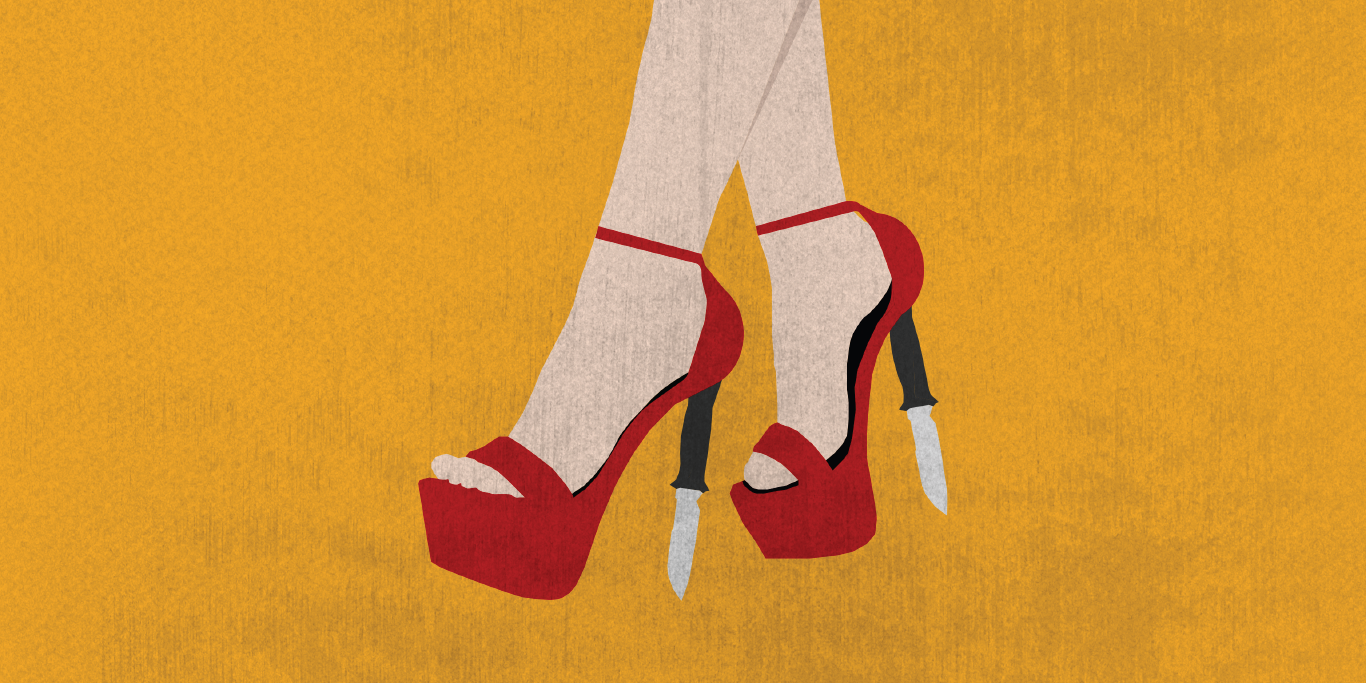

This problem with presenting femininity is not unique to The Kitchen. The trope of a female character who’s good in a fight only because she grew up with ten brothers, for example, is common in action movies. A strong woman can be “one of the guys,” but a weak woman likes pink lipstick, cries when she feels like it, and wants a family. Even when movies include a strong feminine character, more often than not her femininity is hypersexualized. Look no further than the number of slow pans from a woman’s feet to her face in literally any Michael Bay movie. For women in pop culture, there are two extremes, and neither accurately depicts strong women.

The problem is not unique to pop culture. Masculine strength is directly correlated with leadership. Of Forbes’ 100 most innovative CEOs this year, one was a woman. Does that mean women are inferior leaders? No, it means that it’s harder for society to see women as strong leaders because of their femininity. A woman who embodies stereotypically feminine characteristics is seen as too emotional or too sensitive or too warmhearted to be a quality leader. In fact, women in the workplace often alter their behavior to be perceived as more masculine: half feel they need to hide their emotions at work, and one in four purposely dresses in a more masculine way, according to a Telegraph article. When a woman in leadership does embrace her femininity, she is often criticized for it. Take Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, for example, whose bold red lipstick and hoops are used by critics to belittle her and detract from her career.

But women can be strong and feminine. Leslie Knope of Parks and Recreation is a successful politician who celebrates the women in her life on Galentine’s Day and raises a family. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg uses fashion as an expression of her beliefs: she has a collar specifically for when she dissents and another for when she reads a majority opinion. Strength can and should exist not in spite of femininity, but because of it.

As I left the theater, I wondered what my mom and younger sisters thought of The Kitchen. Although we’re all at different stages in our lives, none of us are completely immune to the messages presented in pop culture. I want them to live in a world where they can feel strong no matter what. And for that to happen, we need to see femininity presented as strong, because it is.

Image Credit: Insha Momin