The Iowa Caucuses are only three days away. After over a year of campaigning and endless polls and punditry, we will finally have a real idea of which candidates people actually support. Of course, what the people in Iowa think is not a representation of what the rest of America thinks, given its overwhelmingly white demographics and unique economic interests. Even then, the results of the caucus will not represent the opinion of all Iowans because caucuses inherently make it more difficult for people to participate in voting than a primary election.

Consistently low voter turnout in elections is often blamed on bad nominees. In 2016, many people felt they had to choose between the “lesser of two evils.” Some people even sat out the election because of this (and to them we say, shame on you). This is an easily solvable problem. If people want to have a say in who represents their party come November, they must go out and vote in the primaries.

Nationwide, party nominations historically reflect the decision of only a fraction of Americans. In 2016, just 9 percent of the U.S. population selected either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump as their party’s nominee. Almost 90 million eligible voters “do not vote at all,” according to The New York Times, and 163 million eligible Americans failed to vote in the 2016 primary elections. The nominations were decided by the approximately 60 million Americans who did vote in the Democratic and Republican primaries, out of the over 300 million residents in the country.

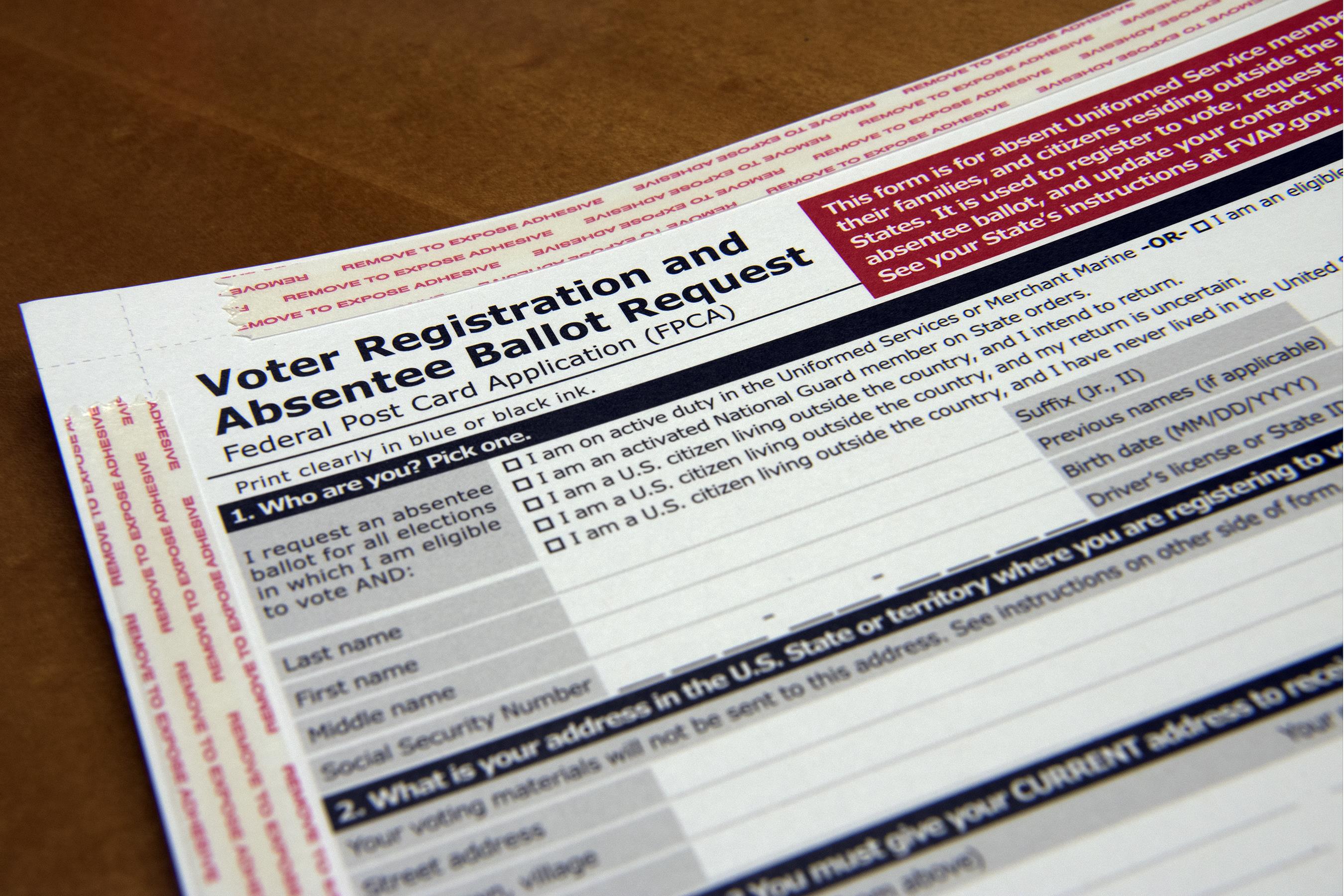

This is partly due to difficulty in voting in any election in many states. For instance, Oklahoma residents who want to vote absentee must have their absentee ballots notarized. Not only does the notarization process require extra time and effort from voters, but it typically costs $5. Voter ID laws, which require registered voters to show ID before voting, also present barriers to voting, disproportionately for the elderly and minorities.

Barriers are even higher in states that select candidates by caucus, such as Iowa. To participate in the caucus, a would-be primary voter must be physically present for multiple hours as each round of the caucus continues. This year, Iowa’s 1,678 precincts will caucus at 7 p.m. on Feb. 3—a time requiring parents to find childcare or workers to request time off a night shift to travel to one of the 1,738 caucus locations. Consequently, would-be voters with families, demanding jobs, and limited resources to travel are functionally excluded from the nomination process.

In August, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) rejected the Iowa Democratic Party’s proposal to expand caucus access with virtual caucusing. This was rooted in cybersecurity concerns—a reasonable worry stemming from the cyberattacks on the 2016 presidential election. Instead, there will be satellite caucuses in 24 out-of-state and three international locations, from Washington, D.C., to Paris, France. But the added sites do not address the problem of demanding people be at a specific place for hours on end in order to exercise their right to vote.

Caucuses as a whole are not viable in contemporary society, and the DNC has actively encouraged states to transition their processes away from caucuses in favor of primary elections. This election season, the DNC mandated that state election committees improve voter accessibility, which is why 10 states made the transition from caucuses to primaries since 2016, and why Iowa implemented satellite caucuses.

While caucuses offer the benefits of community discussion, deliberation, and grassroots organization, this does not justify the exclusionary nature of the practice. Iowa hasn’t made the transition because of the national attention their “first in the nation” status gives them, but the state must reckon with its barriers to voter participation even if it comes at the cost of that status. Caucus states should make every effort to shift to primary elections.

Caucuses highlight the challenges many face when deciding whether or not to cast their ballot. As not everyone is able to vote, like non-citizens and disenfranchised felons, it is even more important that those who can make the individual commitment to do so. Voting is the most fundamental form of participation in the direction of the nation and everyone who can vote should exercise that right as a responsibility. Students who are eligible to vote in the upcoming primary election should go out of their way to overcome hurdles impeding their voting rights.

This year, Georgetown students can register to vote through a portal on MyAccess, as the result of a GU Votes initiative. Students should request absentee ballots as early as possible to increase the chances their ballots will arrive on time, as late and missing ballots are notoriously common.

Voting is the most basic right of a healthy democracy. Local governments owe it to their constituents to make this basic right accessible, and voters owe it to themselves—and those unable to vote—to make their voices heard.