On January 17th, Eminem released his 11th studio album, Music to be Murdered By. The album was met with very mixed reviews from critics, who praised Eminem’s technical command, but thrashed the album for weak lyricism and poor handling of the subject matter. Formerly one of the most towering, intimidating forces in music, Eminem has been rendered a mockery as a result of his horrendous track record: the 2010s have seen him relentlessly releasing one critical flop after another.

Music to be Murdered By is riddled with hamfisted attempts at provocation. On “Unaccommodating” alone, he references Osama bin Laden, JonBenet Ramsey, John Wayne Gacy, church shootings, and the Ariana Grande concert bombing—all within a song that fails to pass the four-minute mark. It’s absurdly over the top.

Eminem’s reliance on dark topics is a thread running throughout the project, with songs such as “Darkness,” “Godzilla,” and “I Will” continuing the focus on violence. His constant references to violence have the opposite of the intended effect, however. Eminem does not come across as threatening or intimidating. Rather, he is reminiscent of an attention-seeking 12-year-old in a Youtube comment section, spouting off whatever offensive remarks it will take to get someone to pay attention to him.

The album is not only immature because of its vulgarity. Repeatedly, Eminem reveals himself as an emotionally stunted man who is unable to let go of past grievances. From bringing up old beef with Machine Gun Kelly, to reigniting fights with his ex-wife—who he divorced 12 years ago—to repeatedly attacking critics who disliked Revival (2018), he reveals himself to be an immature artist who can’t accept when an argument is over.

Frequently, Eminem’s lyricism crosses a line into unintended corniness. Wordplay, seen in lyrics like “I stack chips, you barely got a half-eaten Cheeto” and “Cause life is like a penny/’Cause it’s only one percent” are intended to be clever turns of phrase. However, they read like awful dad jokes, but he says them with the same forceful, abrasive delivery that he always uses. Overall, his seeming unawareness of his own corniness comes across as oblivious.

How did it get to this point? It seems incredibly hard to remember a time when Eminem was once considered a driving force in musical innovation. There was a time when you could hypothetically call Eminem one of the best rappers of all time without immediately getting laughed off the stage. His first three studio albums were generally met with positive reviews; people liked him, or at the very least were intrigued by him, because he was rebellious.

Although many people still took offense to his act, at the time, it was fresh. It is not difficult to understand why his act drew so much attention. Inherently, what makes this kind of provocation interesting is that it is unexpected.

However, because Eminem has used this persona for the entire duration of his career, it would be disingenuous to describe it as unexpected. This type of deliberate provocation is exactly what listeners have come to expect from him. These stylistic choices aren’t exciting anymore.

Although he still attracts a lot of attention, it is clear that this is to diminishing returns. His albums have been consistently selling fewer and fewer copies worldwide since Recovery (2010). Additionally, Eminem is painfully aware of his antagonistic relationship with music critics, as previously mentioned. The overwhelming consensus is that he has not released a solid album in nearly two decades. At this point, between the generally negative critical response to his work and declining sales, it is clear that Eminem is stagnating.

Almost without fail, the highest points on the album (which are few and far in between) involve Eminem being outshone by almost every guest artist on the record. Each of his collaborators comes across as more energetic and more compelling than the main artist.

On “Unaccommodating,” Young M.A. comes across as effortlessly self-assured and confident, making Eminem look strained in comparison. Anderson .Paak starts out as a bubbly presence on “Lock It Up,” only to get bogged down immediately by Eminem’s verse. On “Godzilla,” Juice WRLD’s flow fits the backing track much better than Eminem’s choppy delivery. Practically without fail, Eminem is shown up by his younger collaborators.

Rather than making the album better, these collaborators expose how truly awful Eminem’s presence on the record is. These collaborations make the listener acutely aware of the failings of the main artist.

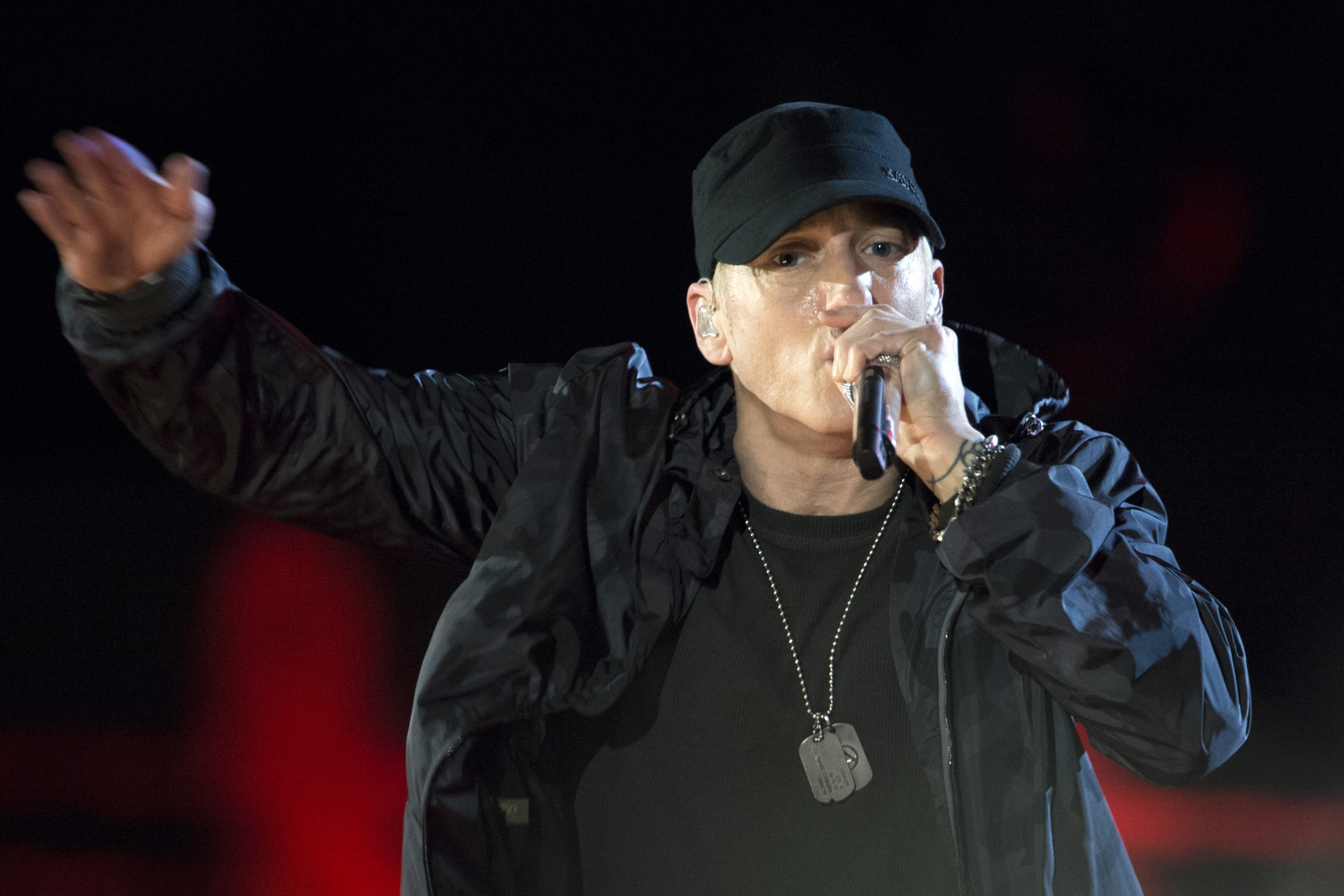

When his career first took off, his image was more cohesive. When Eminem first broke into the mainstream, he was in his late 20s. It made more sense that he was rebelling against norms of politeness, given his youth. However, his claim to his young provocateur persona has long expired. He’s 25 years and 11 studio albums into his career. He’s 47 years old. At this point, Eminem is practically an elder figure in rap. He desperately needs to adopt a new persona, and embrace his position as an older voice in pop music. It’s time for Eminem to pass the reins onto his younger, far more interesting contemporaries, or it’s time for him to get a new bit.