If humans are one thing, we are stubborn. We get things wrong all the time—but boy we do our darndest to prove that maybe, just maybe, we can warp and wrangle our objectively incorrect solution into one that works despite its flaws. You might be thinking, “Hey Cam, projecting a bit much there, buddy?” That may be. Even still, I can prove my hypothesis right here, right now, with today’s date as a shining example. There are few oddities so poignant and representative of our resistance to reality as the Leap Day.

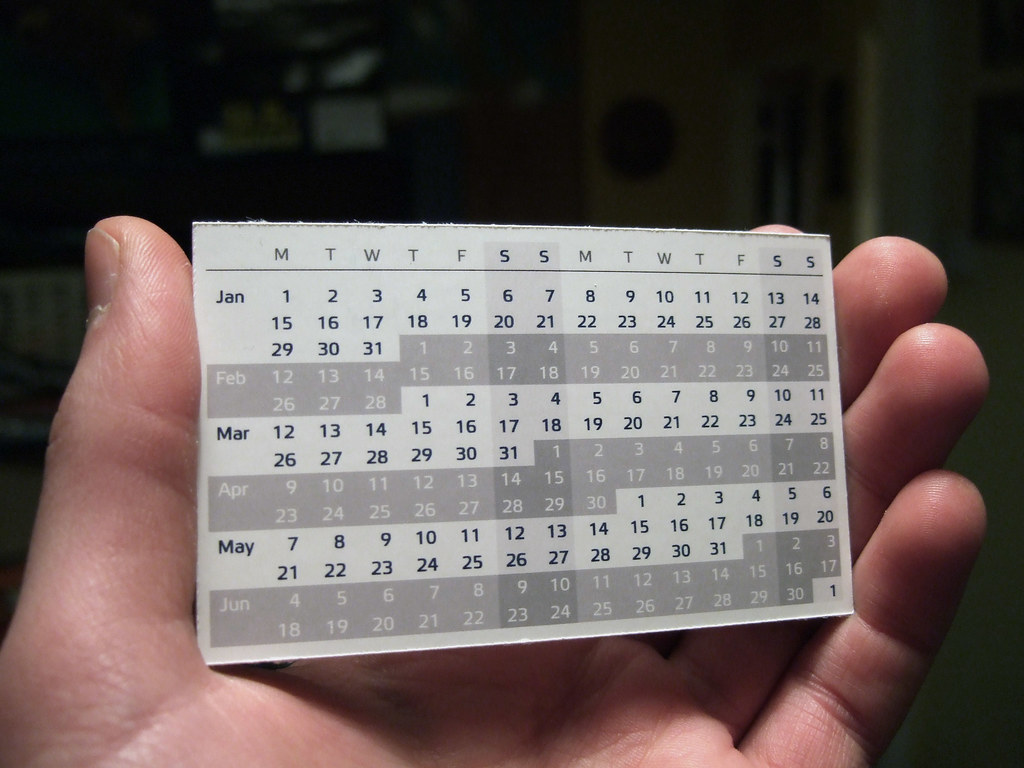

Every four years, presumably due to the shoddy napkin math of some dude hundreds of years ago, we are blessed with an extra day shoehorned into our calendar. The logistical ramifications of this mistake in our calculus are clearly nontrivial. Many an organized folk have mourned the loss of their definitely-a-gag-gift-from-a-friend Firefighters Gone Wild calendar because of a misprint having to do with this awkward little day of leaping.

For those with Leap Day birthdays, their date of birth is sometimes not recognized as a valid in poorly designed computer systems. Computer scientists are required to be keenly aware of such idiosyncrasies in arbitrary human systems lest we end up with another Y2K type deal where there is a non-zero chance that the entire world comes crashing down. Perhaps this is a good time to mention that the actual Y2K is quickly approaching, only a few short leap days away.

But back to the issue at hand. “Why do we have Leap Days, anyway?” you might ask. Shockingly, the universe tends not to operate exclusively with nice round integers like you and me. Instead of a clean 365 days to fly some 92.96 (there it goes again) million miles around the Sun, the Earth’s orbit is more like 365.25 days. But that’s ugly and we don’t like it. So we save up those quarter days like a young lad saving up for a dollar sodie pop from the corner store and every four years we get to cash in on an extra day in our year. All is well in our quest for cosmic chronometry.

Sike. That’s the wrong numba. If I had taken more chemistry classes I would tell you about the importance of significant digits. But I’m not a psychopath, so I didn’t.

The Earth’s orbit is actually more like 365.256 days. Meaning we need some more rules to hit our target of temporal truth. To make up for those thousandths of a day, every hundred years we are viciously robbed of a glorious Leap Day. So, while we are lucky enough to have an extra day in 2020, the people of 2100 will be deprived of theirs (assuming climate change hasn’t ended civilization by then). The outrage over the AWOL Leap Day will surely cause an uprising the likes of which we have never seen.

“But Cam,” an active reader born in the 1900s might say, “I vividly remember feelings of euphoria during Leap Day in 2000! Surely you must be mistaken.” Good catch, reader. Our system as described thus far is incomplete. It is true that every 100 years we lose a Leap Day, but much like a young lass collecting her quarters for a dollar candy gumdrop, every fourth 100 years the gift of Leap returns. Meaning that while 1900 was not and 2100 will not be years of leapage, 2000 was and 2400 will indeed be leapy.

So now you see why a Leap Day is such a momentous occasion. Instead of redesigning our system of dates in accordance with the solar system we actually live in, we have manufactured a heap of kludgy corrections into a beautiful manifestation of our own inability to admit having been wrong.

When I told my editors I would be writing this piece, I was met with cocked heads and probing questions. “But what’s your angle,” they cried. For events that come once a year—Halloween, Christmas, your birthday (unless you were born on a Leap Day)—there is no angle. A Leap Day is an even more special event—it only comes every four years (or so)—and it should be celebrated.