Content warning: This article references sexual assault and suicide.

On the wall of the Renwick Gallery there is “Sunshine on a Cannibal.” Rectangular canvases placed closely together create a jarring visual of distorted culture. In this piece, Andrea Carlson reexamines the definition of “exotic,” creating one image from the art of various civilizations. In this way the piece is a representation of Western “cultural cannibalism.” There is the illusion of symmetry as the piece unfolds from an ancient building in its center, however, further examination reveals subtle differences in the two halves. Hands, faces, crests, mountain ranges, ships, and many unrecognizable shapes flow out from the center overlapping each other in a chaotic wave.

This mashing together of symbols reflects the efforts of the West to describe everything foreign as “exotic.” This collision of cultural symbols is topped off with bold phrases such as “insert trigger warning” or “in cases where the subject is also the primary audience.” The longer the viewer examines this piece, the more subtle details they notice. Through her art, Carlson, along with many of the other artists featured in the Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists exhibition, takes back control of her culture’s narrative.

“Sunshine on a Cannibal” by Andrea Carlson

Giving a voice to those who have been obscured by history, Hearts of Our People explores the creative narratives of Native American women through visual mediums. Displayed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery, the exhibit is part of a four-venue national tour. A selection of the pieces are available for viewing on the Smithsonian American Art Museum website. Hearts of Our People was organized by Jill Ahlberg Yohe, associate curator of Native American Art at the Minneapolis Institute of art, and Teri Greeve, an independent curator and member of the Kiowa Nation, with the help of Native artists and scholars.

Never before has there been an exhibition of this size and detail entirely focused on Native women and their artistic creations. The 82 pieces range from sculptures and paintings created with traditional techniques to photography and media with modern messages. The diversity and sheer volume of pieces, only a minute fraction of those in existence, present a clear visual of the power and ingenuity of Native women and the rich histories they represent.

The exhibition flows through four rooms of the Renwick, each dedicated to a specific theme. The first room displays pieces dedicated to the concept of legacy, bringing together the past, present, and future with pieces from antiquity placed alongside modern art. Artists incorporate both traditional techniques and innovative methods, thus combining their own vision with the knowledge that has been passed down to them.

The first thing the viewer notices when they walk into the room is a collection of strings and oblong forms hanging from the ceiling. This large installation, titled “Idiot Strings, The Things We Carry,” fills the center of the space. Created by Sonya Kelliher-Cobs in 2017, the installation explores the crisis of suicide within the Alaskan Native community. Kelliher-Cobs seeks to explore her Iñupiat and Athabaskan ancestors’ connection to the environment by finding ways to include skins, fur, and membranes into contemporary artistic creations. The strings and rawhide pouches are suspended from the ceiling with thin nylon lines creating the illusion that the pieces are floating in the air. This large-scale installation is a striking introduction to the exhibition and a perfect representation of an artist combining tradition with innovation.

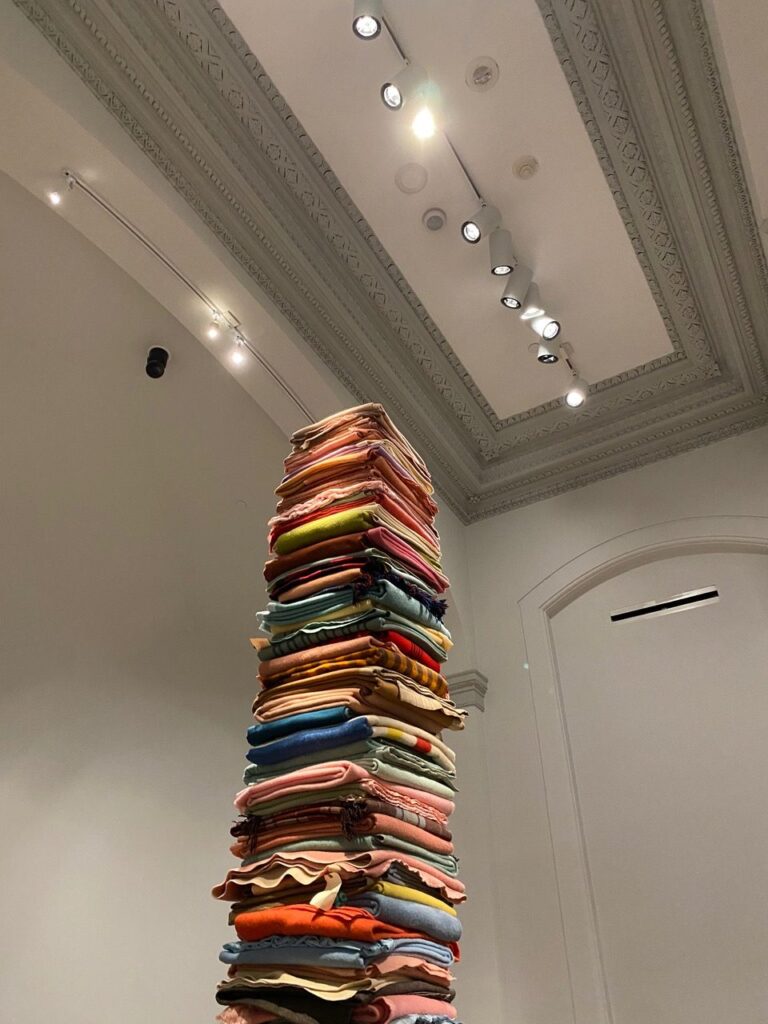

“Blanket Stories: Three Sisters, Four Pelts, Sky Woman, Cousin Rose, and All My Relations” by Marie Watt

Next is a deceivingly mundane onyx black pot. The simply titled “Storage jar” was created in 1940 by Maria Martinez and her husband Julian Martinez. Maria Martinez, one of the first Native women artists to be named in art museums, is famous for developing the style of blackware pottery. Together with her husband, Maria Martinez created rich black ceramic pots, decorating them with slightly lighter black decorations. The artists drew from traditional Pueblo techniques, experimenting to create black pottery from the lighter clay of the region. Due to its international popularity, Martinez’s work served as many people’s introduction to the techniques of the Pueblo community, earning this storage jar its place in the legacy section of Hearts of Our People.

The exhibit then transitions from the large scale concept of legacy to the more intimate theme of relationships. Native cultures place great significance on the interconnectivity of the world, highlighting the importance of reciprocity and balance. The pieces that fill this room are the result of friendships, family bonds, and community connections.

One installation in this section towers above the rest. “Blanket Stories: Three Sisters, Four Pelts, Sky Woman, Cousin Rose, and All My Relations” channels the totem poles of the Pacific Northwest where artist Marie Watt grew up. Standing at 12 ½ feet tall, the installation is made from blankets of various colors and patterns neatly folded on top of each other. The artist cites many different inspirations for this piece including the Native lore of the Three Sisters and the mythic Seneca figure known as Sky Woman. The blankets individually stand for important moments in a person’s life like weddings, funerals, and graduations, which involve members of the community coming together. The artist chose to represent these moments with blankets because their exchange is symbolic amongst Native cultures. This piece draws the viewer’s eye not only for its magnitude but also due to its relative simplicity. Though the pillar is deliberately vague in its meaning, it is instantly clear to the viewer that it stands as a symbol of culture and community.

The final and largest section of the exhibition is titled “power.” What has been an underlying message amongst the previous installations is on full display in the bold and moving pieces of this portion. These pieces are a demand for change carried on striking colors and powerful images.

“The Wisdom of the Universe” by Christi Belcourt (see cover image) is an acrylic painting that features endangered or extinct flora and fauna from Canada. The subjects are made from colorful dots that stand out on the black canvas. By incorporating these many species into a unified image, Belcourt hopes to illustrate how everything in the world is interconnected. She calls for a more sustainable lifestyle, saying, “All I want to do is give everything I have, my energy, my love, my labor—all of it in gratitude for what we are given.” The bold colors against the large dark canvas, particularly the blue vine arching through it, make it stand out in the gallery.

“PochaHaida” by Lisa Telford

Many pieces in the exhibit call attention to the sexual abuse and objectification that many Native women suffer. One such piece, “PochaHaida” by Lisa Telford, reimagines the well-known story of Pocahontas through an artistic rendering of the dress Pochahontas wears in the Disney movie. Telford transforms the story from an over-commercialized cliché to a story of the power and intelligence of Native women. The dress, suspended from the ceiling by clear lines, immediately catches the viewer’s attention due to its recognizable shape and style. However, the surrounding pieces, a picture of a woman with brutal stitches across her back or an acrylic depiction of female council members, prompt one to reconsider the narrative they’ve previously been sold.

The exhibit finishes with a small room entirely dedicated to Marianne Nicolson’s “Baxwana’tsi: The Container for Souls.” From Nicolson’s Dzawada’enuxw culture, the installation represents the relationship between body and soul. A lightbox in the center casts a shadow on the surrounding walls creating a beautiful display. As the viewer steps into the room, they become a part of the art, distorting the images on the wall with their shadow. Small photographs of young Native children are included amongst the tribal patterns etched in the glass, incorporating the individuals behind the art into the piece. This installation is an excellent way to conclude the exhibit as it is a powerful example of art reflecting the culture and people behind it.

“Baxwana’tsi: The Container for Souls” by Marianne Nicolson

It is difficult to create one grand display from the art of many different cultures without losing some elements of individuality. One way the exhibit attempts to combat this is by including descriptions for the art in both English and the native language of the artist’s tribe. There are plaques in Inquait, Cherokee, Pottawatomi, and Navajo, among many others. Not all of the descriptions have been translated as some are still in progress. Other Native communities chose not to translate their label, a decision the gallery wishes to respect. The choice to specifically use the language of the artist’s tribe reflects an effort to illustrate the uniqueness of the cultures represented. The most important element of this translation is the choice to present the native language translation on the left. As English reads left to right, most viewers will instinctively look to the leftmost passage when reading the description. By placing the native language to the left, the exhibit emphasizes that the art belongs primarily to the people who created it, not to the museum or the viewer. These subtle decisions serve to keep the native cultures at the center of the exhibit.

Hearts of Our People is a powerful and extensive representation of the artistic tradition of native cultures through the specific lens of women creators. The variety of mediums conveys messages of legacy, relationships, and power to the viewer repeatedly from multiple angles. It is impossible to confine the exhibit in one style just as it is impossible to limit Native women to one stereotype or role. This exhibit highlights the diverse tradition of long-standing cultures that face the challenges of the modern world with legacy, relationships, and power.

[…] Source link […]