You know college football? The sport where Scott Cochran earned $595,000 as University of Alabama’s strength and conditioning coordinator this past year? The sport where Cochran’s athletes created $77 million in annual revenue for a program they got no salary from? Yeah, you may be familiar.

You’d be crazy not to lament the twisted economics of college athletics, and fixing these systems is where every re-imagination of the National Collegiate Athletic Association should start and finish. I spend my fair share of time questioning the priorities of society and my own priorities in this regard. But in the words of Georgia Bulldogs beat writer Seth Emerson, there will be no hand-wringing or pearl-clutching in this exercise. And with that disclaimer out of the way, let’s begin a ridiculous hypothetical.

The Problem

The College Football Playoff is the Holy Grail. Nationwide exposure, oodles of television revenue – every one of the 130 schools with an FBS football program longs to get there to reap these benefits. The thing is, though, the number of teams with a snowball’s chance in Tuscaloosa of making it to the four-team CFP is much, much smaller than 130. That’s because only a handful of schools (think Alabama, Georgia, Ohio State, etc.) can throw around massive amounts of money to reinvest in capital projects that attract top players, earn more gate revenue, and so on. But it’s also because of these finicky things called conferences.

There are five so-called “power” conferences in Division I FBS – the Big Ten, Big 12, Southeastern, Atlantic Coast, and Pac-12. Then, there are five other “Group of Five” little guys – the American Athletic, Mountain West, C-USA, Mid-American, and Sun Belt. In between the Power 5 and Group of Five exists a colossal chasm. The Power 5’s revenue hauls come largely in the form of television contracts, while the same deals are much, much smaller for members of the G5 conferences. And no matter how strong a football team a G5 school might field, that G5 moniker will hang over them.

Fans will remember the 2017 Central Florida Knights, who finished the regular season a perfect 12-0. Well, in the eyes of the College Football Playoff selection committee, UCF didn’t have a schedule worthy of a CFP berth. After the season, UCF’s head coach was lured to the University of Nebraska, their top players graduated, and the team may very well have returned to G5 purgatory. On the other side of the chasm, P5 powerhouses found a few hapless lower-division teams to play and plump up their win-loss records before going about their regular conference schedule the rest of the season – if they navigated that slate with one or two losses, they would still have a strong chance of getting to the Holy Grail.

And therein exists the other inequity plaguing college football, the exploitation of unpaid labor being the first.

Andrew Elsass goes into much better depth explaining this problem. Simply put, though, college football is played along a P5/G5 divide that predetermines which schools will (and which schools won’t) earn eye-popping television revenues, regardless of the quality of their team, and in doing so, will stay on top of the sport’s hierarchy. Even more disconcerting, these lines were essentially drawn based on which schools were friendly a century ago.

The big boys won’t be able to duck UCF much longer in our hypothetical.

Keep in mind that college football teams are tasked with seeking out their non-conference opponents every season, rather than this being handled by a central body, and a clearer picture of the issue emerges. There’s no incentive for P5 schools to schedule tough matchups, especially against top Group of Five teams, and so G5 programs like 2017 UCF are left out in the cold despite compiling a once-in-a-generation squad. Why would a team like Georgia play against UCF? Georgia’s end-game is the Playoff. A game against UCF is a roadblock that offers little benefit with a win (Georgia will still likely make the CFP with a weak non-conference schedule as long as they handle their in-conference schedule) but presents massive downside in that Georgia is doubtful to make the Playoff if they fall to UCF ahead of conference play.

The Proposed Solution

We’re done with conferences as they’re currently devised. Instead, how about groups that teams can move between based on merit? Everyone needs to get a shot, or at least more of a shot than the G5 schools are currently being given to ascend the college football power structure. And no more competition-avoidance from the big boys. While we’re at it, since this is already a big-big-big project, let’s try and confront some of the other issues facing college football. What follows, which has a precisely 0% chance of ever being implemented into practice in some form, is what I came up with.

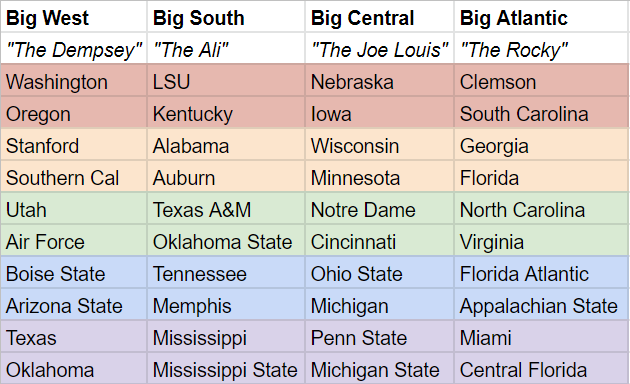

130 FBS teams divided into three tiers – each tier will have four geographically-reasonable groups of teams that will square off as a stand-in for what’s currently conference play. Tier 1 consists of 40 teams – four groups of 10. Tier 2 will be the same. Tier 3 will have two groups of 13 and two groups of 12 to accomodate all 130 programs.

For a jumping-off point, though so much has still been left to be explained, I’ll flesh out the formula I used to allocate the teams to their respective groups. Overall, it’s relevant to keep in mind that programs had to be divided to some extent based on the unfair nature of college football as it has existed for decades – the blueblood programs, even if they have experienced a below-standard year or two, will still likely land in the top tier because it’s not helpful to put relatively underfunded programs that have been punching above their weight class in Tier 1 from the jump and expect an entertaining product.

F+ is a ranking rooted in analytics of each team’s skill, which is influenced by not only their performance, but also by the quality of each team’s opponents. This is where teams like UCF will shine, but they’ll be somewhat dinged for playing against lesser teams. “Program Revenue” is exactly that – an annual number that Forbes has available on the vast majority of FBS teams. This figure was included in the formula because of the aforementioned desire to generally have teams that are on equal footing from a resources standpoint play each other at first. “2019 Recruiting” is the ranking of the school’s recruiting class in 2019 per 247Sports, and “4 Year Rank” is based on a proprietary formula Bill Connelly created to give a snapshot of the total talent on a team’s roster based on recruiting results over the last four years. Both figures are highly correlated with program revenue and were included to create exciting games between teams with similar access to talent. But F+, the measure of each team’s actual performance with respect to strength of schedule – is most important to us in this exercise. So, I allocated teams based on a composite ranking consisting of two parts 2019 F+, two parts 2018 F+, one part program revenue, one part 2019 recruiting ranking, and one part four-year recruiting ranking. I gave respect to geographical considerations and rewarded teams like Air Force with exceptional on-field results, but the formula dictated just about everything.

Here’s how it shook out, and here is the spreadsheet with the formula results:

This is the first tier, with each top-level group affectionately named after a heavyweight boxer hailing from that part of the country since you’re all now hopelessly ensnared in my quarantine-warped dreams (that’s Rocky Marciano, the only heavyweight to finish his career undefeated, mind you, not the fictional Rocky that slugged it out with Apollo Creed). The different colors denote the two schools in each group that will play annually in a super-sized Rivalry Week of sorts, as in this simulation each team will meet every member of their group every other year because of our shortened five-game “conference” schedule, though they will play their “rival” every season.

A few striking points include the Red River Rivalry between Texas and Oklahoma moving to The Dempsey in the west, as the Pac-12 has not been nearly strong enough over the last few seasons to support a large number of Tier 1 teams in this exercise. Additionally, the top-heavy balance of power in college football shifts from south to east as Georgia and Florida arrive in The Rocky to give Clemson the types of in-conference juggernaut they haven’t met in the ACC recently. Each group has at least one Group of Five representative, with The Rocky touting three G5s. Elsewhere, iconic rivalries like Alabama-Auburn, Michigan-Ohio State, Georgia-Florida, and so on stay intact (though some utterly random rivalries had to be conjured in the process). And, of course, I wouldn’t deprive the college football world of Lane Kiffin-Mike Leach Mississippi-Mississippi State Egg Bowls in the top tier.

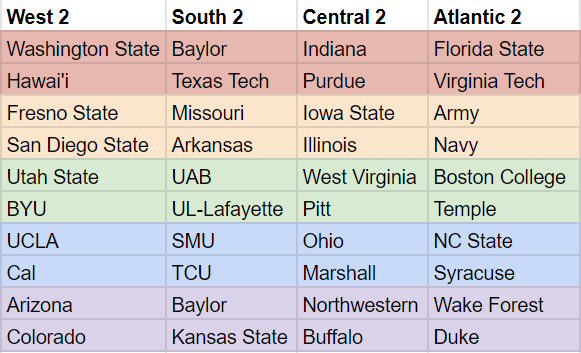

There’s the second tier, which essentially epitomizes why I believe this exercise is valuable. Despite the totally unbalanced flow of resources to Power 5 schools disproportionately over G5 schools, there are G5 Tier 1s, Power 5 Tier 3s, and a total blur of the P5/G5 line in Tier 2. This middle tier treats us to the Nick Rolovich bowl in Washington State-Hawaii every year, the (Insert Insurance Company Here) Fallen Giant Rivalry between Florida State and Virginia Tech, Army-Navy, the Old Oaken Bucket between Indiana and Purdue, and adds up to a congested, wacky mess that college football fans could come to adore (especially when the promotion and relegation measures are explained).

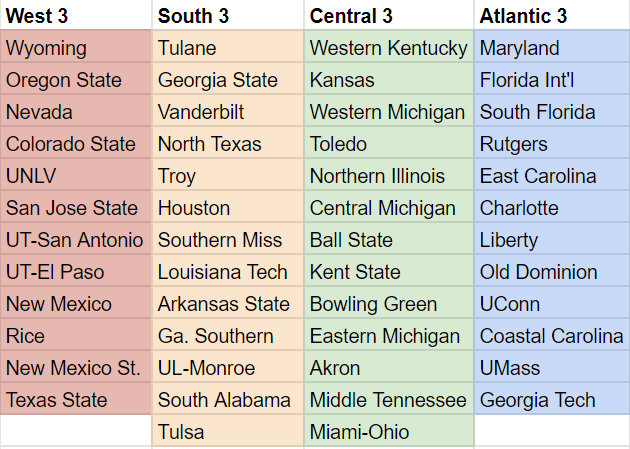

Here lie the also-rans of college football, with some ignominious falls for six Power 5 teams. There are no rivalries at the Tier 3 level, because they play a different schedule than the Tier 1 and 2 Teams.

The Schedule

This was one of the quite difficult parts of this hypothetical. College football teams currently play an eight or nine-game conference schedule as part of a twelve-game regular season. These can often serve as endless warmup laps for the powerhouses of the country – besides a one-point win in a slip-up against North Carolina, Clemson didn’t play a single ACC game within thirty-five points in 2019. The challenge here was to create a balance of rivalry games, within-group, across-group, and across-tier matchups, plus some cupcake breezes for the Tier 1 teams. Each of these types of games serve a distinct purpose.

Rivalry Games: Passionate tilts that attract TV/gate money and engage fanbases

Within-Group Matchups: The top team from each Tier 1 group (and other squads, too) will advance to the College Football Playoff, so it’s best if these CFP candidates can be easily differentiated beyond simply win-loss record if they played a head-to-head matchup, or at least some common opponents.

Across-Group Matchups: We don’t want any teams that end up in the CFP having received a free pass in their non-group matchups. Tier 1 games between teams from different areas of the country are made-for-television programming that attract a wide audience.

Across-Tier Matchups: Similarly, to build out a complete resume for CFP admission, we need to give Tier 2 teams the opportunity to “punch up” and take down a Tier 1 team, and the Tier 1 teams can’t just avoid the plucky underdogs and gain a CFP berth based on the strength of their in-group results.

Cupcake Games: Any game between a Tier 1 and Tier 3 or an even lower-level FCS team will likely be a blowout, but that doesn’t mean they’re not important. For quite a while, top-level teams have paid disadvantaged opponents to come to their stadium and get crushed – but that sum the weaker team receives often constitutes a significant percentage of their annual athletic department revenue and allows these smaller schools to continue to fund other athletic programs and give out scholarships. It would be cruel to completely do away with this system.

With that being said, here is how a potential 11-game schedule might look.

Tier 1 and 2

- Five games within-group (playing each school within the group every other year, one “rivalry” opponent to be played every year. Ex: Stanford vs. Boise State)

- Two games across-group (same tier, different area of the country, with opponents to be determined via a lottery. Ex: Clemson vs. Southern Cal in Tier 1, Missouri vs. Buffalo in Tier 2)

- Two games across-tier (Tier 1s will play Tier 2s in the same area of the country, opponents also TBD via lottery. Ex: LSU vs. Kansas State)

- Two games free to schedule independently (likely to be used to schedule Tier 3 or FCS teams. In some cases, maybe athletic directors will wish to schedule a rival that isn’t in the same group as them and isn’t on their schedule. Ex: Wisconsin vs. Southern Miss, perhaps Florida vs. Florida State)

Tier 3

- Seven games within-group

- Four games free to schedule independently (Likely to be used to gain playing fees from Tier 1 and 2 teams looking for an easy win, or to be used to schedule FCS teams in efforts to collect a win and get closer to a postseason bowl game)

In this version of a potential schedule, the regular season is condensed from 12 games to 11. Because one of our goals stipulated at the outset was to challenge some of college football’s inherent inequities, an eleven-game regular season would allow student-athletes to travel, practice, and put themselves at risk of injury less often. A shortened regular season is practically antithetical to the job description of athletic directors, because it means less overall game-day revenue for their school at the very least, and for many programs, they’ll play five home games against six road contests (gasp).

And about that lottery I ever so slyly alluded to above – in the link from earlier, Elsass has a tremendous simulation of what a potential centralized lottery determining non-conference matchups (as opposed to schools scheduling these games on their own) could look like. I haven’t done away with independent scheduling completely here – in fact, Tier 3 teams are still tasked with scheduling a pretty typical four games, so they have plenty of open dates to show Tier 1 and FCS teams alike.

Oh, but there will be a lottery, and it will be glorious. Elsass calls his Selection Saturday – you better believe the NCAA will monetize the living sh*t out of whatever they come up with, a la March Madness.

Ohio State has only played Auburn twice in its history – but they drew the Tigers in my first simulation.

To paraphrase, imagine Gary Barta, chairman of the College Football Playoff, just before reaching into a fishbowl reading: “Medium South”

“Louisville and the rest of the college football world, welcome to the 2021 College Football Scheduling Convention presented by TaxSlayer. As defending national champions, Louisiana State University will begin the 2021 season squaring off against…”

The lottery would be used to give LSU and the rest of the Tier 1 and 2 schools their two across-group and two across-tier matchups. In year one, it could also be used to give all Tier 1 and 2 schools their other in-group games (besides the locked-in rivalry week) for that season – each school would then play the remaining schools in their group the next season. That is, if they’re still there…

Promotion and Relegation

This is the ace of spades card in any college football hypothetical. It’s tempting to say if the sport wasn’t so darn stuck in its ways ensuring the Vanderbilts of the world see a Brinks truck of TV cash their teams do nothing to merit, it would have been implemented years ago. But that would be unfair. Many of us fans put our football-only goggles on when discussing this stuff, but teams like Vanderbilt baseball and Kansas basketball can do a great deal to raise a conference’s prestige even if these schools’ football teams don’t pull their weight.

You may be familiar with the concept of promotion and relegation, which has long been in place in European soccer. The system is simple: the worst teams in a given tier during year one get dumped to compete in the tier below in year two, and in their places rise the best teams from that lower tier, who now get their chance to perform on a bigger stage, against stiffer competition, with more money on the line. And while I can give you a Joe Namath guarantee that promotion and relegation will never be instituted, it sure is fun to think about.

Here’s how it could look. Florida Atlantic could have an awfully tough time in a post-Kiffin era competing in The Rocky (the top tier of the Atlantic). Let’s say they finish in last place in 2020 – they’re automatically dropping a tier to the Atlantic 2 for 2021. Conversely, if Mike Norvell’s hiring pays immediate dividends at Florida State, they could make quick work of the Atlantic 2 and finish in first place – they’re directly promoted to The Rocky for 2021. So, at least one member of every group in every tier is guaranteed to change year-to-year. But up to two teams in each group could change. That’s because I envision the second-worst team in each group playing the second-best team from the tier below in a one-game postseason battle for a spot in the higher tier the following season. For example, if Miami can’t figure things out and finishes 5-6 in The Rocky, ahead of only Florida Atlantic, they would play the second-best team from the Atlantic 2 (perhaps a 9-2 Navy) in a neutral-site showdown for the final spot in the 2021 Rocky.

The U’s athletes against the Navy triple option for a spot in The Rocky? If only.

There would be eight of these do-or-die games for better tier placement every season, and they have incredible potential. They’re made-for-TV programming that should offset some of the revenue losses from a shortened eleven-game regular season. They’d give the players and fans of the second-worst team in each group something to care about as a disappointing season wraps up and would allow the same people from the second-best team in Tier 2 to pick themselves up after a near-miss for a shot at the College Football Playoff. In the Tier 2 vs. Tier 3 do-or-die game, both teams would be engaged in a battle to avoid a season on the periphery of the sport in Tier 3. Tiebreaks between teams with the same record could be settled on the basis of conference record, and if those records are also knotted, the spot could go to the team with the better in-group point differential. Now, to round everything out…

The College Football Playoff and the Postseason

There is an impressive amount of unanimity among athletic directors and fans alike that eight teams is the best size for the College Football Playoff. But, simultaneously, most everyone is sick and tired of the CFP committee justifying one team’s inclusion (or exclusion) based on largely subjective sentiments about strength of schedule, quality of wins and losses, etc. What’s a better way to settle such matters? With extra games to find out who the superior team really is, of course.

There’s certainly room for each of the Tier 1 group winners in an eight-team playoff field – those teams are directly through to the CFP with seeds 1-4 based on Tier 1 point differential. Seeds 5 and 6 would be awarded after the four second-place teams in Tier 1 play two games against each other, with the winners moving on to the CFP. Options for determining the matchups could be on a predetermined, rotating basis (2nd place in The Ali in 2020 plays 2nd place in the Dempsey, then the following year 2nd place in the Ali plays 2nd place in The Joe Louis) or the four second-place teams could be seeded by point differential against Tier 1 opponents. Similarly, as the G5 teams have been effectively frozen out of the current CFP, we want to give these underdogs an outside shot at a title. The four first-place teams in Tier 2 would play each other in two more games for seeds 7 and 8. The same principles we’ve espoused throughout this hypothetical remain: these would be games drawing a national audience for teams not usually getting that exposure, the subjectivity would be all but eliminated, and there’s more TV money to go around to make up for a shortened regular season.

I’m mostly indifferent on whether the rest of the bowl system remains in place. At present, almost all of the profit generated during bowl season comes from the Playoff and the remaining few premier non-Playoff bowl games, so it doesn’t seem to make much sense to make a bunch of Tier 3 schools (who will likely now have better records in this simulation given they’re playing an easier overall schedule) spend a large chunk of their budgets chartering planes and whatnot to get to some Beef-O-Brady’s-type bowl games. At the same time, they may appreciate the national exposure.

So, let’s take stock of where we are.

What a Season Would Look Like

Tier 1 Teams:

- 11 regular season games

- Direct admission to the CFP for first-place teams (3 games maximum)

- One-game CFP play-in for runner-ups (with an opportunity to play up to 3 CFP games)

- One-game survive-or-relegation matchup for second-last team against Tier 2 second-placed team

- Potential bowl games for a good number (probably the majority) of teams

Tier 2 Teams:

- 11 regular season games

- One-game CFP play-in for champions (with an opportunity to play up to 3 CFP games)

- One-game promotion-or-stay matchup for second-place teams against Tier 1 second-last team

- One-game survive-or-relegation matchup for second-last team against Tier 3 second-placed team

- Potential bowl games for a few teams in each group (including losers of CFP play-ins and participants in promotion-or-stay games)

Tier 3 Teams:

- 11 regular season games

- One-game promotion-or-stay matchup for second-place teams against Tier 2 second-last team

- Potential bowl games for a handful of teams in each group (including participants in promotion-or-stay games)

So, at the most, a team could play 15 games, which is also the largest number of games currently possible. This would be rare and would require a team to win a CFP play-in and then make it to the CFP title game. Most schools would play 11, 12, or 13 games.

Sample Schedules

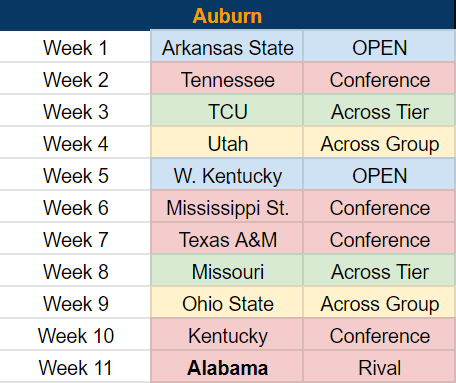

For illustrative purposes, I created mock schedules using a random number generator to simulate what a team in each tier could draw at a Selection Saturday lottery. I listed what “type” of game each matchup was next to the opponent.

Here’s Auburn’s draw, which didn’t do them many favors. Even with the locked-in matchup against Alabama, their schedule in The Ali is a gauntlet, though they’ve seen worse in the SEC West. Games against South 2 squads TCU and Missouri aren’t gimmes either, and drawing Utah and Ohio State across-tier puts an exclamation mark on an altogether-grueling schedule. Most Tier 1 teams won’t be dealt such an unfavorable hand, but therein lies the beauty of the lottery. Auburn would be deemed one of the “big losers” in the post-lottery chatter, and we’d be blessed with seeing Gus Malzahn shift uncomfortably from side to side in a live feed from campus and all the memes that would be spawned afterward. Could you imagine?

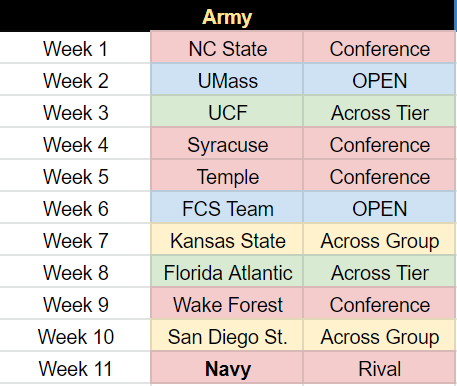

Conversely, Atlantic Tier 2 team Army likely wouldn’t mind their draw at all. They avoid Florida State and Virginia Tech in-conference, but would have to play each team the following season if they remained in Tier 2. Kansas State and San Diego State make for fun stylistic clashes across Tier 2, and they draw very winnable punch-up opportunities against UCF and Florida Atlantic. Army would get the opposite of Auburn’s treatment – an easier schedule than they expected. Could they be promotion candidates if they return to 2018 form?

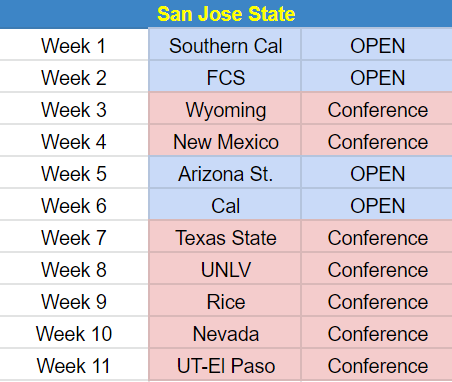

There won’t be too many surprises for Tier 3 teams like San Jose State at the lottery. The only games they’ll be drawn for are their in-conference matchups, and it’s up to them to decide their remaining four opponents. In this mock, SJSU opts to secure some extra revenue with away dates against three Tier 1 and 2 teams on the west coast against only one FCS game. The decision to schedule top teams or easier opponents for Tier 3 athletic directors would be an awfully important one and adds another interesting wrinkle to this discussion.

The final thing that’s definitely worth touching on is how home and road games are decided. Assuming a Tier 1 or 2 team uses both of their open dates to schedule low-level opponents at home, that leaves nine remaining games (determined by the lottery) to try and get to any athletic director’s golden number of seven home games during the course of the season. As it would play out, maybe the lottery could determine who is home and away for each team’s first few draws, and then some wizard programming could allocate home or away for the remainder of games to get to either four or five home games from the draw for each team. Throwing around suggestions, Elsass mentions home field advantage potentially going to whichever team is ranked higher or willing to pay more, and the possibility of a neutral scheduling czar dictating who is home and away and how much money is being exchanged.

Thanks for joining me for this exercise, which I’ll be the first to admit veers away from a feasible re-imagination of college football toward something that will simply never happen, what with our disbanding of conferences and promotion/relegation system. Being in a power conference is so valuable for its members because it brings predictability, allowing schools to accurately forecast their revenues and fund capital projects, scholarships, and other athletic programs accordingly. And when the P5 power brokers wield more influence in college football, we’re not likely to see measures enacted that will narrow the P5/G5 divide. But…everyone with a shot at the top? CFP play-in tilts? Win-or-relegation games? Muhammad Ali shows up? It sure is fun to think about.

Email me (fsw7@georgetown.edu) with thoughts/critiques/other angles on this!

I love it!