In light of COVID-19’s outsized effect on the Black population, as well as sustained protests over the police killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and many other Black Americans, faculty and students at Georgetown have sought to reflect on issues of racial justice.

In response, the university’s Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity and Affirmative Action (IDEAA) kicked off a series of conversations between faculty members on June 25. Rosemary Kilkenny, the vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion and chief diversity officer, introduced each of the three sessions so far.

“The questions posed by the audience have been insightful and thought provoking and have inspired members of our community to initiate informal gatherings with friends in their home communities,” Kilkenny wrote in an email to the Voice. The discussion series has drawn between 125 and 225 participants each session, and, according to Kilkenny, will have a future beyond this summer.

The chokehold and the American criminal legal process

Professor of African American Studies Robert Patterson, who served as the inaugural chair of that department, interviewed Professor of Law Paul Butler in a discussion about policing and prosecution. The hour-long conversation served as an overview of systemic discrimination in the pipeline from policing to the courtroom to prison.

Butler himself began his career as a federal prosecutor, representing the government in the District. “I used that power to put Black men in prison, and Black women, and Latinx people and poor people,” Butler said, and said that held true for most of his fellow prosecutors as well. “If you were to go to the criminal court in the District of Columbia, then or now, you would think white people don’t commit crimes.”

Even with firsthand experience of the racialized criminal court system, the full extent of its discriminatory practices only hit Butler when he became a defendant himself. Arrested and prosecuted for a crime of which he was innocent, Butler said he owes his lack of conviction to a combination of stellar legal representation and his prior experience.

“I had prosecuted people in the same courtroom that I was being prosecuted. I had a kind of social standing,” he said and then admitted, “We made sure the jury knew stuff that shouldn’t matter but does.”

Butler had to play up his education and reputation as a prosecutor, emphasizing the characteristics for juries, even though they have no bearing on the truth. Patterson added, “Your defense attorney had to remind you about not getting angry on the witness stand because that might persuade the jury to have a different outcome.”

“That experience made a man out of me; it made a Black man out of me,” Butler said.

Patterson then steered the conversation toward police practices and the lessons that he feels have gone unlearned since the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson in 2014. In order for an officer to search someone, they must only have reasonable suspicion, he said. “And we have a very energetic conversation about what suspicion is reasonable when Blackness is already suspicious.”

“The problem isn’t ‘bad apple’ cops. The problem is the system is working the way it’s supposed to,” Butler added.

An Obama-era report on policing found that officers conceived of themselves as “warriors” and recommended a shift in thinking to a role focused on guardianship. Butler’s own research led him to numerous use-of-force continuums that outline in detail the escalation of force in police officers’ arsenal, from a “command presence” to lethal force. Physical beatings and shootings, then, are a taught behavior in police departments across the country, he said. With a system such as this, Butler said, the racially-skewed outcomes are not a surprise.

While Patterson and Butler discussed both overt racism and implicit bias, Butler said, “I don’t think that cops are any more racist than law professors or politicians or anybody else. But, at the law school, we’re not licensed to kill. That’s the difference.”

They finally transitioned into a discussion about movements to defund the police, which Butler described as “justice reinvestment.” “When people call 9-1-1, most times, they don’t need someone with a gun and baton and the power to arrest. In many situations, having that guy with the gun makes things worse, not better,” he said. Instead, Butler sees value in reevaluating which first responders arrive at different types of incidents.

The growing crisis of health disparities in American society

The second event in the series was even more closely tied to a discussion of the nation’s capital itself. Associate Professor Edilma Yearwood, chair of the Department of Professional Nursing at the School of Nursing and Health Studies, engaged Associate Professor Christopher King, chair of the Department of Health Systems Administration at the school, in a conversation about racial health disparities in American society. COVID-19 has exposed existing inequities in painful clarity, Yearwood said.

“[It] was a catalyst, but it was also an accelerant to an underlying problem that has always existed.”

King explored this underlying problem in both an initial and an updated report on the state of healthcare and race in the District, based on pre-pandemic data. “When we look at the District of Columbia, our health profile is really good,” he said, pointing to high fitness levels and life expectancy. “But when we stratify data by race and ethnicity, it’s an entirely different narrative.”

The numbers themselves are striking: rates of diabetes are seven times higher in Black people than white, deaths due to heart disease are two-and-a-half times higher, and three-quarters of COVID-related deaths occur in Black residents. This racial health disparity is not an isolated problem; rather, it reflects larger trends of societal inequity. The median household income of white residents is three times higher than Black residents; 22 percent of Black families in the District are below the poverty line, compared to just one percent of white families; and just 26 percent of Black residents have an undergraduate degree or higher, compared to 90 percent of white residents. Comparing Wards 3 and 8, the former affluent and white and the latter impoverished and Black, King found a difference in life expectancy of 15 years.

These differing outcomes are partially a result of mistrust from people of color towards white doctors, Yearwood pointed out. “When our population interfaces with the healthcare system, what are those biases they’re met with?”

King gave an explanation of historical mistrust of healthcare workers, who he said have not done enough to address a history of racial exploitation. “It’s important for us to educate students and anyone in the healthcare space—they need to understand the history and evolution of healthcare and how Black and brown bodies were used to advance the practice of medicine in some of the most inhumane ways,” he said. The archetypal example is the 1932-1972 syphilis study at the Tuskegee Institute, where Black patients went untreated, even with the medicine available, and uninformed of the study’s purpose: to study the progression of the disease rather than cure the patients.

The mistrust can perpetuate a cycle of worse outcomes among Black residents if they refuse treatment or vaccination or face racial bias when they do seek help.

A resolution requires collaboration between health educators, local healthcare providers, and community leaders, according to King. “Our health care system has to work with public health and community health leaders, folks who are on the ground, who know the community, who can provide that education that’s so important.”

King added that the arrival of the pandemic has provided new opportunities to educate others. “Those of us who do this work, for so long we’ve been trying to get this message out. And now finally folks are connecting the dots.”

How racism permeates American institutions

The third discussion investigated how institutional power structures perpetuate racial discrimination. Associate Professor and Chair in Sociology Corey Fields spoke with Associate Professor of Sociology Becky Hsu about the influence of organizations on racial identity and structural barriers to professional and social mobility.

“Organizations can structure how people understand their own racial identities,” Fields said. His own research explores how Black Republicans conceive of themselves in the organizational context of the party.

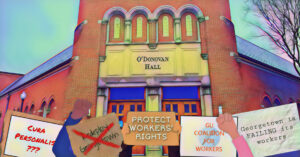

Much of the conversation evaluated strategies for increasing institutional diversity and the dissonance between public messaging and internal problems at some organizations. As many companies rushed to put out public statements in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, Fields said they were often met by a backlash from their own employees.

“I think it’s critical for organizations to think through not just what you’re saying outwardly, but how is what you’re saying outwardly being aligned with what’s happening internally,” he said. “It seems like a lot of places need to get their own house in order before they can start public conversations about this.”

Hsu furthered the point, asking how institutions can be proactive about producing justice themselves. She spoke about the way an institution’s environment changes the behavior of its members, saying, “It’s rare that it’s just a ‘bad apple.’ People are in these webs of formal and informal roles, so they can only do things if the environment allows them to or promotes a certain thing.” This web includes de facto practices at institutions as well as hierarchies embedded in their structure and internal rules, she noted.

Even offices responsible for diversity and inclusion may still have duties to superiors who influence their work, Hsu pointed out. “One thing we can look at is organizational charts, but mapped by race. Who answers to whom?” she added.

Citing studies about implicit bias affecting hiring practices and promotions or raises, Hsu and Fields moved into a discussion of various approaches to addressing the problem, with an emphasis on corporate and academic environments.

Fields recognized that improving institutions is not a quick fix process. But he did offer advice for creating lasting changes that can remain effective beyond the efforts of one person. “I would focus on trying to change practices, not people.” Fields said. “You’re probably going to be much better served thinking through how you want your place to run as opposed to thinking through how you make everyone in the organization feel the way you do about something.”

Hsu added that even with the advent of hiring and promotional algorithms deemed to be unbiased, these tools can still perpetuate systems already in place. If an algorithm places emphasis on seniority, for instance, when making decisions, it may carry on the current structure because a given company has in the past allowed mostly white employees to occupy these positions.

In the process of bettering our institutions, Fields emphasized that the burden should not fall on Black employees. Too often, he said, Black employees are asked to do informal—and unpaid—work educating their white colleagues and taking responsibility for diversity initiatives without compensation or advancement.

And both agreed that the problem does not end with increased representation; power and authority must accompany these changes to make them last. Fields said, “It’s not enough to just have the people there; you also have to have something in place that emboldens the people there.”

********

The series will continue with at least three further discussions between Georgetown colleagues on other relevant topics. Kilkenny wrote that the next conversation, titled “Black Women as Voters, Candidates and Officeholders,” will be an “uplifting discussion that will hopefully influence our audience to vote in the upcoming elections for national, state and local representatives and result in even more women climbing the political ladder.” After receiving positive feedback, Kilkenny plans to extend the series virtually through the fall semester as well, looking to integrate students as well as faculty.

“We have to take steps to respect each other’s humanity and demonstrate that we genuinely want our society to live up to the ideals of freedom, justice and equality,” Kilkenny wrote.