This piece appears as part of our Alumni Speak column, featuring incisive, necessary commentary written by Georgetown alumni.

Like many Georgetown students, my journey to campus began on an airplane. At the start of my freshman year, I landed at Dulles airport and joined thousands of other “out-of-District” students commuting by plane, train, and car to move in and start orientation. For the past few years, less than 2 percent of Georgetown undergraduates have been from D.C. According to Georgetown’s student profiles from 2017 and 2019, the most recent years publicly available, there were fewer than 30 students from D.C. in each incoming freshman class. Needless to say, Georgetown has not been much of a “local” school.

Now that most students will not be returning to campus in the fall, the local happenings of the District may be the last thing on the minds of 7,000 remote students scattered across the nation and the world. But right now, it’s more important than ever to look at our nation’s capital. D.C. stands at a historical crossroads.

Over the past few tumultuous months, D.C. faced issues no state would. While states received at least $1.25 billion dollars in COVID-19 pandemic relief funding, D.C. received less than half of that: $500 million. This disproportionate distribution of funding is especially unfair given that D.C. has a larger population than Wyoming and Vermont. Moreover, in June, President Trump unleashed military police and the National Guard onto D.C. to harass Black Lives Matter protestors, flaunting an abuse of executive power and ultimately confirming the systemic racism of the American police system. While governors are in charge of state National Guard units, the D.C. National Guard falls under the authority of President Trump, not D.C. Mayor Muriel E. Bowser. With limited “Home Rule” and no state sovereignty for the District, Congress can overturn D.C. local laws and budgets. Mayor Bowser is politically disenfranchised to make critical decisions involving federal troops for her own jurisdiction. In short, D.C. cannot defend its own interests when lacking the resources and political power that states have.

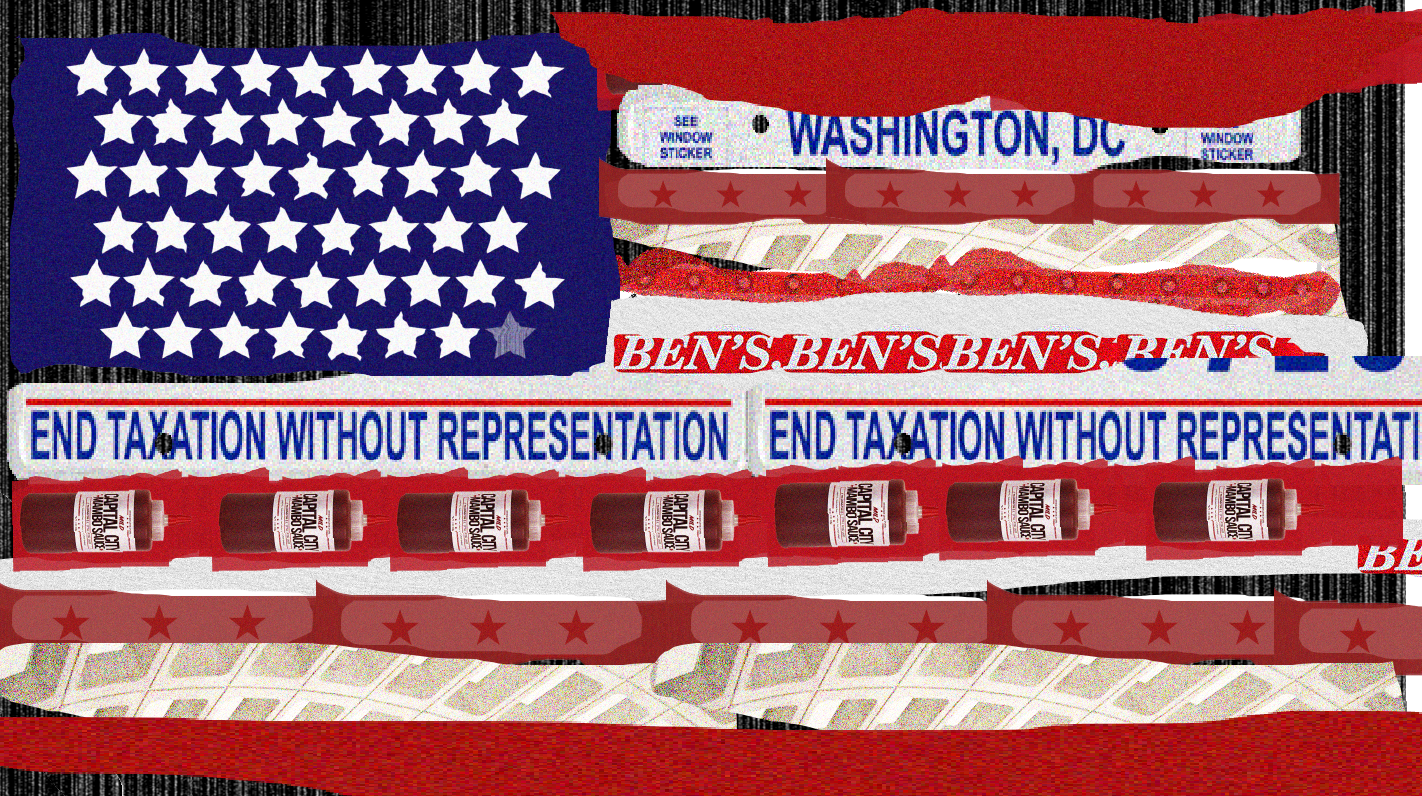

Things, however, may soon change. On June 26, the House passed H.R. 51, a bill that would turn D.C. into a state and fulfill the goals of D.C. statehood movements that have existed for centuries. Since D.C. is not a state, its residents lack voting representation in Congress—a cornerstone of American democracy that all states possess. While D.C. has a congressional delegate, the delegate cannot cast a vote in the House or the Senate. When D.C. congressional delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton introduced H.R. 51 onto the House floor and testified, she herself could not vote on the bill she had advocated for on behalf of the residents she represents. Despite D.C. residents fighting for “No taxation without representation” since the 1800s, it was not until the passage of the 23rd Amendment in 1961 that the District was allowed to vote in presidential elections. Since then, there have been many efforts to achieve statehood. In 2016, the D.C. local referendum for statehood received support from 79 percent of D.C. voters. The overwhelming majority of D.C.ists are tired of disenfranchisement. The successful passage of H.R. 51 is a historic victory that has brought the fight for D.C. statehood closer to its goal than ever before.

However, this critical move now lands D.C. statehood in the most vulnerable arena: a GOP-controlled Senate. Support and opposition of the bill have fallen sharply across party lines with all 178 House Republicans voting “Nay” and all but one of 233 House Democrats voting “Yea.” Republican members opposed the bill as unconstitutional and argued that D.C. statehood “violates the intentions of our Founding Fathers,” who wanted to establish the District as neutral territory. Since the political makeup of D.C. is overwhelmingly Democratic, several Republican senators have spoken against the bill out of concern that D.C. residents would elect Democratic representatives, add blue seats to Congress, and shift decisions in favor of the Democratic Party. Since H.R. 51 was able to pass in the House because Democrats comprise the majority, policy experts anticipate that the statehood bill will not fare as well in the Republican-dominated Senate. The voting rights for D.C. residents, Democratic and Republican alike, will likely die on the Senate floor.

D.C. statehood is not an issue of just taxes or borders. Civil rights, racial justice, and democracy are at stake. Statehood would open up pathways for the 700,000 residents of D.C., 54 percent of whom are people of color, to advocate for themselves and access the same democratic processes that people living in states do. Since federal interference limits D.C.’s authority, the D.C. government struggles to implement and fund its own legislation on marijuana legalization, gun violence prevention, and abortion access. Furthermore, even though D.C. pays more in federal taxes than 22 states and has a larger population than Wyoming and Vermont, D.C. residents are deemed second-class citizens by the electoral process. This is especially troubling given that D.C. has long been a “majority-minority” city with a historically large population of Black residents. Part of the opposition to D.C. statehood is based on structural racism and disenfranchisement of Black communities. No member of a democracy should be denied the right to representation on account of their residence.

If you are an out-of-District student, you may be wondering: but what does this have to do with me? As a California resident myself, I already have full congressional representation and designated congressional offices. It’s easy to forget about the political issues of a city you don’t permanently live in. When I evacuated campus in March, I didn’t know if I would ever come back to D.C. Still, that doesn’t mean I’m no longer connected to the city. D.C. has been a home, however temporary, to me and the overwhelming majority of Georgetown students. During my four years at Georgetown, I relied on the residents of D.C. to cook the food at my favorite restaurants, operate the bus and metro I rode, and maintain the parks I walked in. As a guest of the District, I owe it to my neighbors to advocate for their right to self-governance and representation. It is our responsibility to stand with the District and demand that Congress make D.C. the 51st state. Instead of being a transient bystander, I want to invest back into the future of D.C. and be an ally rather than an invader.

Furthermore, my four-year presence in D.C. as a college student was far from neutral. Each year, I’ve participated in a migration of thousands of young college students whose movement has a larger impact on local communities than one would initially presume. The fact is, universities are some of the biggest gentrifying forces, and Georgetown is no exception. Universities actively facilitate gentrification by funneling thousands of young adults into surrounding neighborhoods. College students graduate as highly-educated young professionals, take the best-paying jobs in the area, and often displace low-income residents from their longtime homes. This is especially true for Georgetown, a predominately white and wealthy institution that has attracted similarly white and wealthy residents to the neighborhood, driven housing prices up, and uprooted Black residents since the early 20th century. The book Black Georgetown Remembered, authored by Carrol R. Gibbs, Kathleen M. Lesko, and Valerie Melissa Babb, reports that “The Black population of Georgetown fell from nearly thirty percent of the general population in 1930 to less than nine percent by the 1960 census, and the racial diversity that had been so much a part of Georgetown’s historical character was virtually lost.” Real estate companies, policymakers, and white residents implemented racist and elitist housing policies that engineered the white, upper-class neighborhood of Georgetown that we know today.

While I only lived in Georgetown for a few years and my permanent home was thousands of miles away, I cannot deny that as a Georgetown student, I was part of a gentrifying institution. The historically Black communities of Georgetown were pushed out by businesses like H&M and cupcake chains that moved into the neighborhood to cater to student consumers like me. D.C. may not be my home, but that does not excuse me from responsibility to the local D.C. community—especially as a non-Black, non-indigenous person of color. As someone who was privileged enough to move to D.C. voluntarily, how can I be mindful of those who were ousted by the very institutions that brought me to this city? In addition to supporting Black-owned businesses and signing the petition to urge Georgetown to cut ties with the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department, I can stand in solidarity with D.C. residents by demanding a major change to the ways in which local D.C. government and politics run: the admission of D.C. as a state. I can call the senators who represent me and pressure them to support the bill when it comes to the Senate floor. While statehood in itself won’t fix issues of homelessness, gentrification, or income inequality in D.C., it will create the structural political change needed to more democratically confront the city’s issues.

Indeed, 2020 has brought about unprecedented loss, tragedy, and disruption, but it also welcomes unprecedented hope. In this unique time for D.C., the statehood movement is at its apex. For those who are able, call your senator on behalf of those who can’t. Tweet at senators and urge them to pledge their support. For more information on D.C. statehood and how to stay involved, follow the Georgetown University chapter of Students for D.C. Statehood on Facebook and Twitter, and check out the 51 for 51 campaign.

Note: This op-ed is based on my personal experiences/views but I want to make sure it’s still relatable for other Georgetown students as well. I am very privileged in being able to afford to choose Georgetown while many of my peers did not have much choice in their university applications due to financial constraints, geographic limitations, etc. Furthermore, I am very privileged to have a senator to call, not just as a California resident but also as a US citizen. While I do believe that all Georgetown students benefit from D.C., I don’t want to assume privileges that many students do not have at Georgetown. I do think that the institution of Georgetown is a huge gentrifier, but that is not the fault of individual students. It’s not like there aren’t Georgetown students whose homes are not also being pushed out/gentrified.