When the 11th St. Bridge Park opens in 2024, it will do more than connect neighborhoods on either side of the Anacostia River. Historically, the river has segregated majority-Black, working class, and low-income communities from their whiter, wealthier counterparts on the far bank. Redeveloping the bridge between the two communities could attract jobs and support local businesses—or exacerbate the city’s affordable housing crisis.

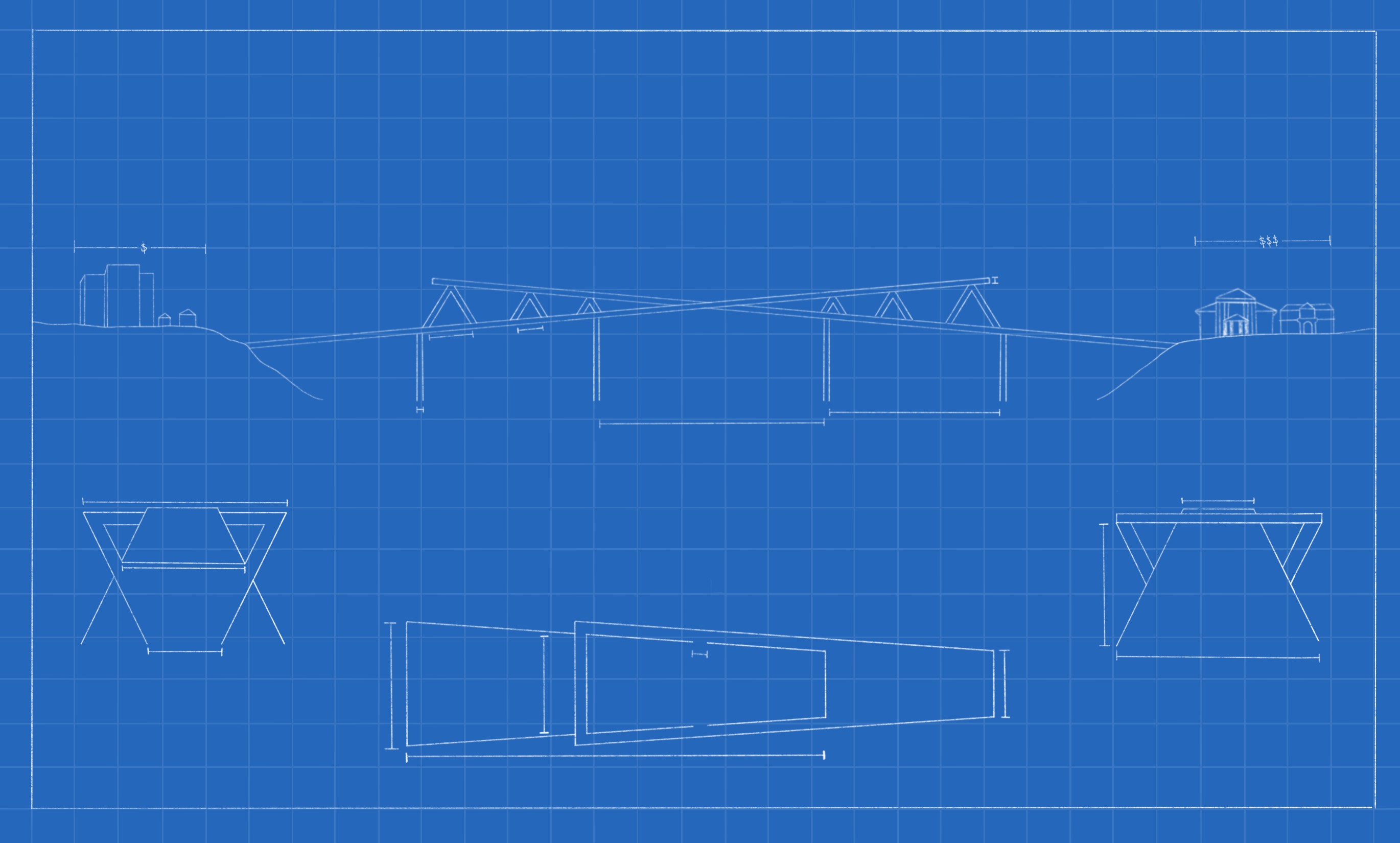

D.C.’s Department of Transportation (DDOT) and Building Bridges Across the River (BBAR) are hoping to use the structure of the existing, abandoned bridge to provide more green space for historically redlined communities east of the river. The park will span the renovated bridge and will connect to land-based parks on either side of the Anacostia.

“The goal that I think most resonates with District residents is bringing people together that wouldn’t usually cross paths,” BBAR Vice President and 11th St. Bridge Park Director Scott Kratz said at a virtual project update meeting on Oct. 6.

Alongside creating space for recreation and public events, designers hope the park will connect residents of the Anacostia and Fairlawn neighborhoods to economic opportunities from which they have been excluded. BBAR has touted job creation in construction, landscaping, retail, and hospitality, as well as increased traffic to local businesses surrounding the park.

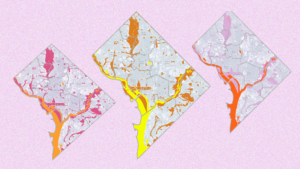

But for a city that, until recently, was the most intensely gentrified in the country, an influx of wealth into poorer, majority-Black neighborhoods is often a warning sign of displacement. In addition to designing playgrounds and public art, project managers—as well as residents and community organizations east of the river—are contending with the possibility that the communities the park is designed to serve will be priced out by its construction.

While the opening of new green space might attract investment and help homeowners build wealth, more than 50 percent of Ward 8 residents near the site are renters. As the park’s amenities are likely to attract wealthier newcomers and increase property value, rising costs may become too much for these renters to bear.

When BBAR—a non-profit that addresses social, environmental, economic, and health disparities between Black and non-Black D.C. residents—pitched the project a decade ago, Ward 8 residents like Sheldon Clark doubted it would actually serve the community’s needs. “I really kind of approached it as a skeptic, initially,” Clark said.

Funded in part by JP Morgan Chase and designed by leading international architecture firm OMA, the proposal came across to some residents as an attempt to enrich developers without addressing racialized access to green space and economic opportunity.

The proposal followed the Great Recession, which disproportionately impacted Black households and widened the racial wealth gap, Clark added. “There was a lot of skepticism in the community around big banks and big institutions coming into the community.”

That’s where the Douglass Community Land Trust (Douglass CLT) came in, where Clark is board chair. Governed by community members and public representatives, community land trusts purchase and maintain property to counteract rising prices. The model legally separates land from the buildings on top of it, allowing, for example, a low-income family to lease a house on a plot they might otherwise not be able to afford. Now in his second term, Clark explained the organization was founded explicitly to maintain local control of housing.

“The notion of a community land trust was one of the solutions that came forward,” Clark said. “I was very pleased with the direction that it was going and really fell in love with the community land trust model through those early days.”

Since those early days, BBAR leadership has held more than 200 public meetings to gather feedback on how to revise its initial plan. In 2015, it published an equitable development plan that aims to better include local residents in the park’s planning and development.

At the Oct. 8 BBAR meeting, 11th St. Bridge Park Director of Equity Vaughn Perry offered an update on the plan’s implementation. “As a long-term Ward 8 resident, what really gets me excited is some of the investments that we have been able to secure for the residents,” he said.

In addition to creating jobs, promoting small businesses, and highlighting local art, the equitable development plan aims to protect and expand local affordable housing. Measures include amplifying information about existing affordable housing options, partnering with housing justice organizations to boost homeownership, and leveraging relationships with the D.C. government to preserve existing affordable housing and build new units.

Like the land trust, BBAR is attempting to avoid the displacement associated with other infrastructure revitalization projects nationwide. A similar effort around Atlanta’s Beltline elevated park devoted more than $14 million to anti-gentrification programs. Still, a 2017 study found that housing prices skyrocketed “between 17.9 percent and 26.6 percent more for homes within a half-mile of the Beltline,” more than elsewhere in Atlanta between 2011 and 2015.

To date, Perry said, BBAR has raised more than $70 million to fund the equitable development plan—nearly as much as it will take to construct the park itself—but if evidence from Atlanta is any indicator, counteracting gentrification is a steep challenge. As the park’s opening looms, Perry and his team are trying to secure tangible, if incremental, victories.

“We focused on tenants’ rights workshops and organizing tenants. We also have been hosting and facilitating Ward 8 homebuyers’ clubs,” Perry said. He added that more than 90 residents east of the river have been able to purchase their homes through these efforts.

It’s this long-term commitment to the community, Clark said, that eventually got him on board with plans for the 11th St. Bridge Park.

“People haven’t had their voices heard. They haven’t had a lot of opportunities for their ideas to be acknowledged,” Clark said of his neighbors in Ward 8. “If you’re there for engagement—not just for outreach—with true engagement, it’s a conversation.”

The 11th St. Bridge Park is scheduled to break ground in early 2023 and to open late the following year. Disruptions caused by the pandemic make it difficult to predict what the D.C. housing market will look like then, but there is little to suggest the city will emerge from its affordable housing crisis anytime soon.

It’s unclear whether the efforts of Douglass CLT, BBAR, and other local organizations will be enough to ensure that Anacostia’s majority-Black residents will not be priced out of access to much-needed green space—or their homes. The trust of their community is hard-won, but policy and industry decisions over the coming years will be crucial to whether it remains intact.