This article is part of “It’s A G Thing”, a 4-part series about the history of the Georgetown men’s basketball team both on and off the court.

“Thompson the n—– flop must go.”

Forty-five years ago, those words were sprayed on a bed sheet at McDonough Arena during a six-game losing streak. To this day, we still do not know who hung the banner. The cowards ran off when the sheet fell to the ground, but the message infuriated the team. That day, the Georgetown men’s basketball team took out its frustrations on Dickinson College, winning 102-60 en route to their first NCAA tournament appearance in 32 years. After three seasons of relative mediocrity and being attacked by fans for the color of his skin, an ordinary coach might’ve folded under the pressure.

John Thompson, Jr. was no ordinary coach.

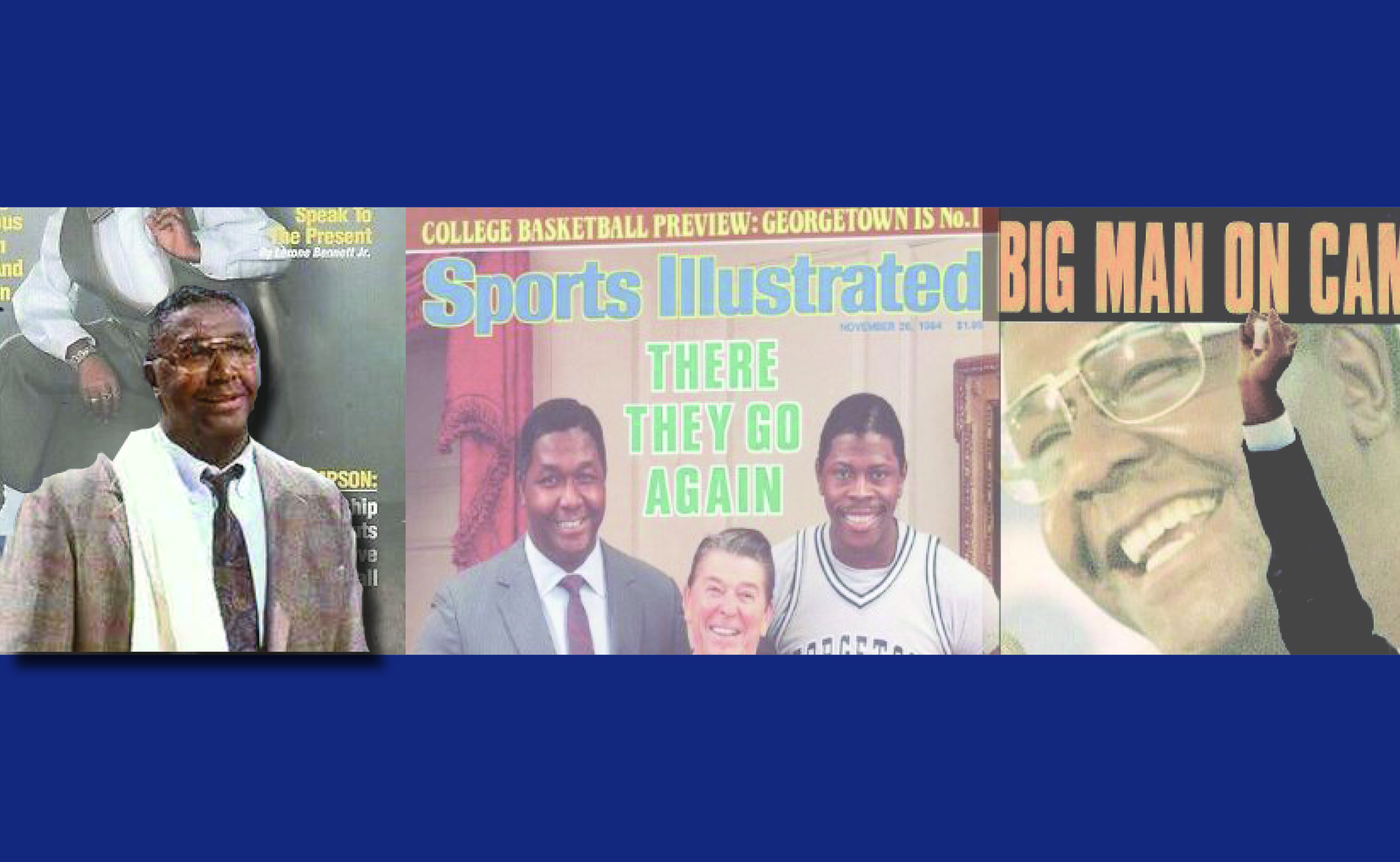

Known by his friends and enemies as Big John, he was a disturbance in the Force. Standing tall at 6’10”, he was much more than just an intimidating courtside presence. For nearly fifty years, Coach Thompson has defined the Georgetown men’s basketball program. He took a program that won three of 26 games the year before he arrived and oversaw a nine-win turnaround. He saw his program through, winning a national championship in 1984 and catapulting the Big East into the top tier of basketball conferences. All the while, he fought racial adversity and spoke loudly where there was injustice, but also where there was progress.

“With the discrimination that’s gone on in sports, to have a Black coach who’s come from those poor areas that’s able to translate and articulate the way Coach Thompson was able to in a time when he was winning, he was a trendsetter in launching and helping to build up a new conference called the Big East,” said forward Jerome Williams (COL ’96).

Georgetown’s teams in the 1980s were molded in Coach Thompson’s image: brash, physical, and dominant. They were a disruptive force for college basketball in that time period, which was defined by Power 5 schools in small college towns. Most teams would do their best to play the game and not ruffle any feathers. The Hoyas took a different approach.

“Our bench used to talk so much shit to the other team! People hated coming down in front of our bench,” recalled guard Gene Smith (COL ’84), the scrappy defensive stopper for the national championship team. “We were always up on the bench applauding and talking, and that was part of the culture.”

They did a lot of winning, too, and they let you know about it. In the 1979-80 season, the first season Georgetown played as a member of the Big East, the Hoyas pulled off one of their most memorable victories, arguably setting the program on the course towards a championship. Led by senior guard John “Bay-Bay” Duren and senior forward Craig “Big Sky” Shelton, they marched into Syracuse’s Manley Field House to decide the regular-season Big East champion, a venue where the Orangemen had not lost in 57 tries. This was to be a coronation, a glorious last game at the beloved arena before the team moved into the spacious Carrier Dome.

Syracuse held a 14-point lead at halftime and led most of the way, but the Hoyas proved to have late life. Spurred by a 15-5 run, Georgetown tied the game at 50. Unwisely, the Orangemen fouled sophomore guard Eric “Sleepy” Floyd with five seconds remaining, and he sank both free throws to win the game, 52-50. It was a monumental upset, and Coach Thompson knew it. “Manley Field House is officially closed!” Thompson thundered in the postgame press conference.

“Big John is a formidable person, and he’s loud and he’s articulate,” said Smith. “That was like saying, ‘Go fuck yourself!’”

Thompson never minced words off the court, and his team backed him up on the court. “Part of the country loved us,” said center Patrick Ewing (COL ‘85), who is the team’s head coach today. “Our physical style, our aggressive, in-your-face style.”

Georgetown’s take-no-prisoners style of play caused a young Williams to take notice during his childhood and into the recruiting process. Born at Georgetown University Hospital during Coach Thompson’s first year, Williams grew up in nearby Bethesda just as the Hoyas were rising to national prominence.

“I remember being a kid looking at Georgetown and seeing Virginia when they had Ralph Sampson and basically cheering for Georgetown because it’s the home school,” recalled Williams.

With the eyes of Black America watching, the Hoyas always used their prominent platform to bring social issues to light. This was a time where many urban communities, including D.C., were ravaged by the crack epidemic, mass incarceration, and homicide. At the height of his cocaine empire between 1986 and 1989, kingpin Rayful Edmond sold an estimated 1,700 pounds of cocaine a month, and the neighborhood he operated in was nearly 95 percent Black. D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department made an estimated 800-900 arrests on weekends. The number of homicides in the city shot up as crack cocaine infiltrated the city, peaking at 482 deaths in 1991.

At the same time, young Black people did not have the same educational opportunities as their white counterparts in suburban areas, and thus had an extremely difficult time exiting this trap. In 1990, just 9.6 percent of undergraduate students enrolled in degree-granting institutions were Black, compared with their white peers making up 77.5 percent of this population. Coach Thompson was determined to provide as many kids with an education as possible in addition to his masterful use of his platform to make the public aware of racial inequities.

This rang especially true on January 14, 1989, when Coach Thompson walked out of the game against Boston College to protest the NCAA’s Proposition 42, which would have required freshmen to have a grade-point average above 2.0 and a minimum score of 700 on the SAT or 15 on the ACT. This rule, centered around racially biased standardized tests still plagued by such problems today, would have eliminated scholarships for 1,800 prospective athletes at the time. Coach Thompson feared that athletes from disadvantaged backgrounds would be disproportionately affected by the rule, and he used his platform to send a powerful and clear message.

Coach Thompson again threatened to pull his team off the floor on January 22, 1995, in a road game against Villanova. Star guard Allen Iverson had been convicted of a felony in his hometown of Hampton, Va., but was granted clemency by Virginia Governor L. Douglas Wilder. Several Villanova fans sensed an opportunity to demonize the young Iverson, so they dressed in prison garb and held signs that said “Convict U”.

“I mean, that’s just horrible, but that shows the systemic racism at its core, and how he dealt with that,” said Williams. “He was getting blasted and put to be made fun of and never saying a word. Never complaining. Never lashing out. It’s a testament to Allen Iverson. I’m glad he was my teammate. I’m so happy he became a league MVP, and even happier that he became a Hall of Famer after being the first person picked in the draft of 1996.”

Georgetown exerted its power in refusing to play opponents that disrespected them for the color of their skin. Actions that defied the status quo evolved into Hoya Paranoia, which was the memorable brand of Coach Thompson’s teams. They were projected by a mostly white media as the villains of college basketball, similar to the Oakland Raiders in the NFL. They derived their strength by embracing this title, endearing themselves to the substantial Black community in DC. Coach Thompson orchestrated it all, spreading the message any way he could.

“To have Georgetown as being one of those main events, whenever people would tune into the Big East, was just wonderful for the black community, because all those other colleges didn’t have all-Black teams,” said Williams.

***

“Thompson the n—– flop must go.”

Forty-five years ago, those words hung off a bed sheet at McDonough Arena, during a six-game losing streak.

Today, a statue of Coach Thompson replaces that sign, in the Athletic Center that bears his name. It represents the disruptive nature of the program’s history, and it is a call to action for the program to be a disruptor today.

Check out Part 2 here.