This article is part 2 of “It’s A G Thing”, a 4-part series about the history of the Georgetown men’s basketball team both on and off the court. Part 1 can be found here.

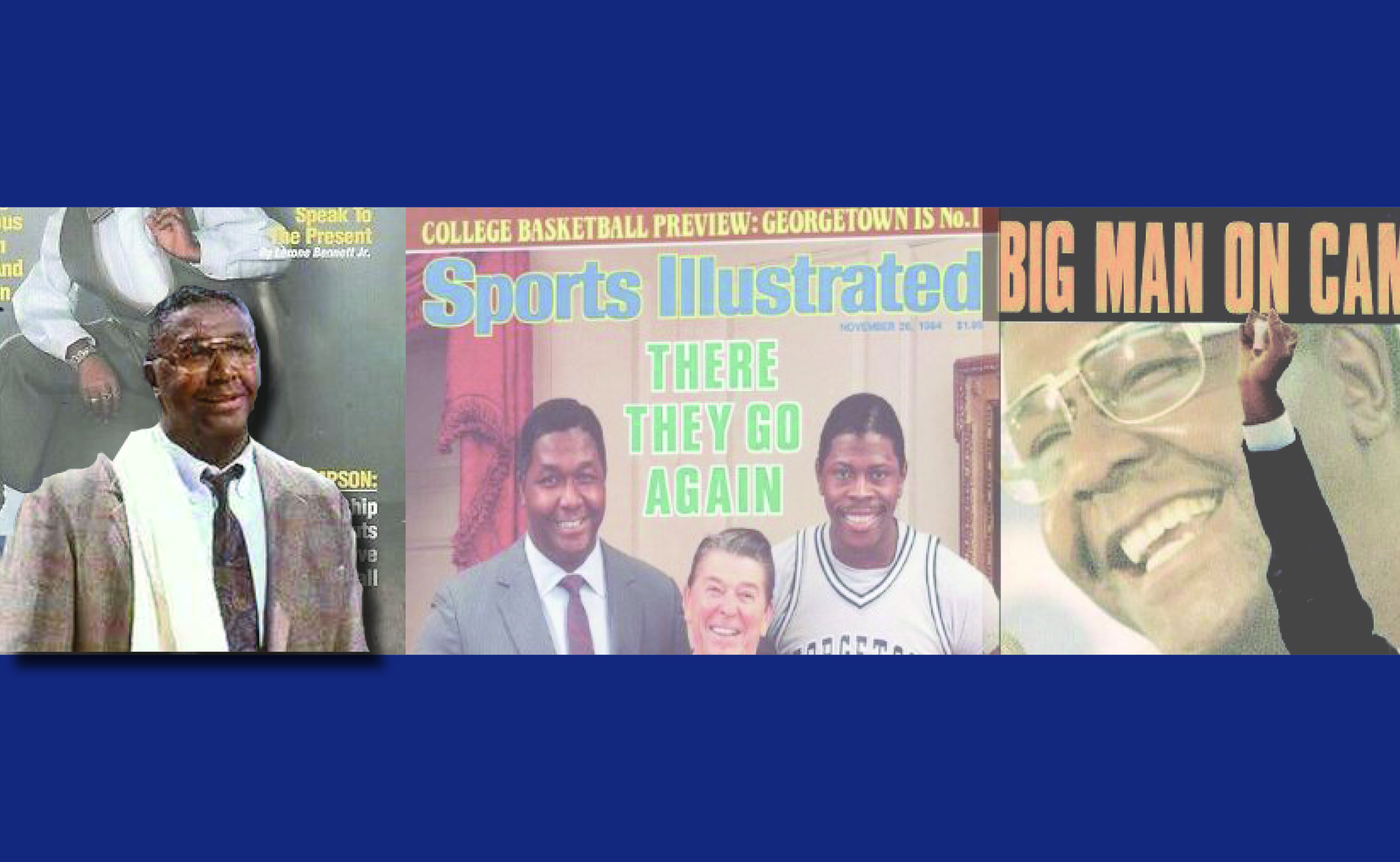

Georgetown is one of the most iconic programs in the history of college basketball, but it wasn’t always that way. Everything changed in 1981. Patrick Ewing (COL ’85) was the one who made Georgetown a national brand and lent the Big East legitimacy, spurning powerful schools such as UCLA and North Carolina. The day former Big East commissioner Dave Gavitt learned that Ewing had committed to play for Coach John Thompson Jr., he knew that all the world had to see what his league had become and moved the conference tournament to Madison Square Garden to seize the limelight. Three years later, the Big East had its first national champion, and the year after that, three of four teams in the Final Four were from the Big East.

Yet, Georgetown had already caught the attention of the nation when they closed out Manley Field House in the inaugural season of the Big East. They had finished that season ranked No. 10 and got to the Elite Eight, proving that they were already a very good team. So, the identity of toughness, perseverance, and grit that marked Ewing’s tenure was already in place by his arrival in 1981. It was the less heralded recruits that made up the backbone of the 1981-82 team and executed Coach Thompson’s vision, and then the highly touted recruits simply fell in line.

Gene Smith (COL ’84) was a lightly recruited prospect out of McKinley Tech in Northeast D.C. Nobody mistook him for the world’s greatest shooter, but he blossomed into arguably the best individual lockdown defender in the history of the Big East. Everybody in the Big East knew that, but he saved his best for the national stage.

Georgetown faced Kentucky in the 1984 Final Four. With three future NBA first-round draft choices, the Wildcats were heavy favorites to whip Georgetown and move on to the National Championship. Their point guard, Dickey Beal, was quoted as saying that he “relished” the challenge of being guarded by Smith in the game.

Beal finished with just six points on a paltry 25 percent shooting from the field, four fouls, and six turnovers, with Smith defending him most of the way. Georgetown held Kentucky to just two points in the first 16 minutes of the second half en route to a 53-40 victory, a defensive masterpiece led by Smith.

Eric “Sleepy” Floyd was a North Carolina native not highly recruited by ACC schools. In just his second game, he would make the conference pay for its mistake, dropping 28 points against Maryland. Four years later, he would become the all-time leader in scoring for Georgetown basketball, a mark that still stands today.

Ed Spriggs was a freshman in 1978 at the age of 26. A former post office worker who never even played varsity ball at his high school in Hyattsville, Md., he soon became an enforcer who set the tone.

“You couldn’t walk across the paint without Big Ed putting that forearm on you,” Smith said. “I give him a lot of credit for Patrick’s success because you couldn’t really gang up on Patrick with him around.”

In 1983, the team’s toughness and resolve were tested in a game at the Palestra against Big East rival Villanova. Ewing had immigrated to Cambridge, Mass. at the age of 12 from his native Jamaica, and ever since, he had faced racist attacks due to his place of origin and his skill in basketball. In high school, Bostonians would routinely slash the tires on his team bus. The Villanova fans resorted to attacking him during the game.

“I remember we were playing at the Palestra, I think, against Villanova. Shit just wouldn’t fly today,” Smith said. “They had the banner up in the rafters: ‘Ewing can’t read.’ They’re throwing bananas.”

That was just one sign Villanova fans had up that night. Some other choice signs read, “Ewing Kan’t Read This,” “Ewing is an ape,” and “Ewing can’t spell his name.” Coach Thompson threatened to pull his team out of the game until the signs were taken down, but Villanova administrators took no preventative action to remove the racist attacks, claiming they could not screen every single sign in the arena.

“Of course, you’re gonna have people that don’t like you, think that you don’t deserve to be there,” Ewing said.

The Hoyas lost a close decision that night, 67-68. Ewing drew from the hurtful remarks from that and so many other nights, channeling that anger into dominating the opposition. Though this further cemented Georgetown’s identity and made them even tougher as a team, Ewing still reflects on the way he dealt with racism in his career.

“I’m not gonna say I did it wrong, but maybe I should have spoken out those times and spoke out a lot for me and my teammates,” Ewing said. “But I love what LeBron and the rest of those guys are doing, speaking out about the injustice that’s going on in this country and the injustice that has been going on for a lot of years, and a lot of it’s still going on as we speak.”

Historically, athletes were expected to “shut up and dribble,” implying that playing a children’s game for a living meant that players were not intelligent enough to comment on social issues. Trailblazers like Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar broke that glass ceiling in the 1960s, but they were roundly criticized by the mostly-white media.

Over time, though, as the public has grown more aware of systemic racism and worked towards finding solutions, athletes have used their platform to bring light on social issues. As Ewing mentioned, LeBron James has been one of the most vocal advocates for social change, and his community efforts have backed up his statements.

“I love what LeBron and the rest of those guys are doing, speaking out about the injustice that’s going on in this country and the injustice that has been going on for a lot of years, and a lot of it’s still going on as we speak.”

By 1984, Floyd and Spriggs were gone, but the culture and identity had been set. Georgetown would never rely on only its stars – it would recruit the toughest kids from the most impoverished areas of D.C. and allow them to flourish while being themselves.

Nobody exemplified this ideal better than forward Michael Graham. An All-Metropolitan forward from Springarn High in Northeast D.C., Graham also was not heavily recruited, so Coach Thompson took a flier on him in 1984.

That decision didn’t pay off until the 1984 Big East championship, one of the defining games in the Georgetown-Syracuse rivalry. The Hoyas were one of the most fearsome defensive teams at the height of their powers. Yet, a little guard named Dwayne “The Pearl” Washington could break them down anytime he wanted to. He paced the Orangemen with 29 points and 6 assists in the game, and Syracuse led most of the way. The Hoyas nonetheless continued to stay in the game, and with four minutes remaining in regulation, a scramble for a rebound underneath the basket led to Graham taking a swing at Syracuse forward Andre Hawkins.

Referee Dick Paparo sprinted into the middle of the skirmish and ejected Graham from the game with arms swinging. Then, he returned to the sideline, where Coach Thompson was waiting for him, just to talk. What was said between the two of them and Syracuse coach Jim Boeheim is lost to history, but somehow Graham returned to the game. Behind his energetic play, the Hoyas rallied to win the game in overtime, 82-71, making them the Big East champions of 1984.

Graham’s meteoric rise would only continue from there. The bald-headed crusader notched a combined 22 points and 11 rebounds over the Final Four match against Kentucky and the National Championship game against Houston, giving the Hoyas the final push necessary to win it all.

Sadly, Graham’s story did not have a happy ending. Due to poor exam scores, he was left off the team for the 1984-85 season, and eventually transferred to the University of DC in Division II. Georgetown lost the championship game to Villanova by two points that year.

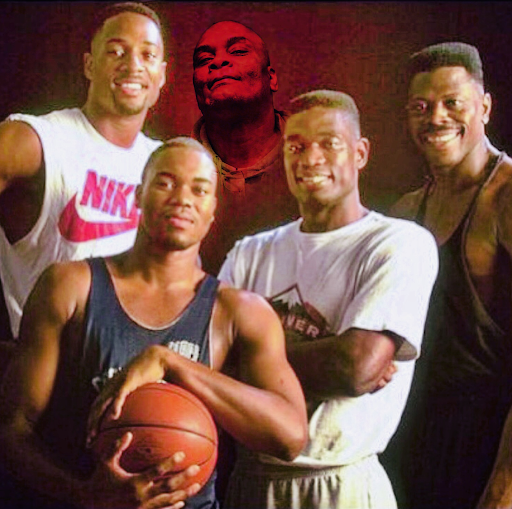

“There was a picture going around of Othella [Harrington], Patrick, Dikembe [Mutombo], and Alonzo [Mourning]. And it was like ‘Big Man U’ or something, and it left off Michael Graham,” Smith said. “Well, I superimposed Michael Graham into the photo because he only played one year but what he did in that one year, and that we only have one championship, you have to recognize it.”

The REAL Big Man U. Photo courtesy of Gene Smith.

The team’s identity mirrored that of Michael Graham: angry, unrepentant, aggressive, and elite. They were also unmistakably Black, with a Black leader spearheading this basketball movement. For much of white America, this was an uncomfortable notion.

“A lot of people thought that Georgetown was a Black school, just because the team was predominantly Black, and also it had a Black head coach,” Ewing said. “There’s part of the country that hated us because of that.”

Being a star on a defiant team that much of the country did not like had consequences for the players, as forward Jerome Williams (COL ‘96) learned at the end of his career. With polarizing figures like Williams and guard Allen Iverson leading the team, the backlash was so great that those who resented the team resorted to extreme actions to express their displeasure.

“Allen Iverson and myself were the only players from that team that did not receive our jerseys from Georgetown. They were stolen out of the equipment room,” Williams said. “We were just told they were stolen, and they were sorry. Now Allen Iverson, they’ve gone on to replicate that jersey so he could always get another one. But my jersey was never to be found ever again.”

As a 6’2” forward out of high school, Williams didn’t attract much interest from high-level programs, so he opted to play at Montgomery College to hone his game. Averaging 26 points and 17 rebounds per game and growing to 6’9” helped his stock rise dramatically with two years of college eligibility left. Yet, his path to Georgetown was certainly nontraditional.

“When I went back to school for that final semester, it opened back up all my recruiting. So then I was back on the market,” Williams said. “What happened then was Coach Thompson came and watched me play on the playground, and he recruited me off the playground.”

Once Williams committed to Georgetown, the rest was history. With career averages of 10.5 points and 9.3 rebounds for the Hoyas, Williams eventually became a first round selection in the legendary 1996 NBA Draft, parlaying that into a decade-long NBA career that included front office roles with the Toronto Raptors and the New York Knicks.

Georgetown’s brand was built on going into poorer urban communities and winning every recruiting battle in the D.C. area. They certainly had their share of five-star recruits like Ewing, but their strategy netted them key contributors like Smith, Floyd, Spriggs, and Williams. Everybody coming in had a chip on their shoulder, just the way Coach Thompson envisioned.

They were great, they knew it, and they made sure everybody else knew it too.

Check out Part 3 here.