Six months after the death of longtime Georgetown professor and former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, friends, colleagues, and students gathered on Sept. 29 in Gaston Hall to commemorate and honor her legacy through anecdotes, tears, and hopes for a more peaceful future.

“Honoring the Legacy of Madeleine K. Albright: A Symposium on Diplomacy” kicked off the morning at Copley Hall with a discussion between professors from across the nation on the ways Albright incorporated her professional experience into her teaching career. The panels continued into the afternoon as domestic and international foreign service figures reflected on Albright’s impacts on diplomacy, how far women in foreign service have come, and how far they have yet to go.

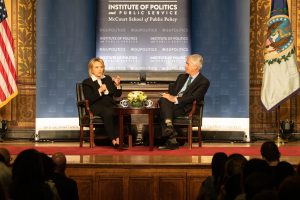

The first panel featured foreign affairs ministers from El Salvador, Israel, and Sweden; next, two American ambassadors; and the third, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and President Bill Clinton, both of whom elaborated on how Albright shaped U.S. foreign policy and her transition from Georgetown professor to Secretary of State.

Albright began teaching at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service in 1982. Throughout her tenure, her classes like the renowned “American National Security Tool Box” course were immensely popular.

“Out of any professional titles she had, Madeleine loved being called professor the most,” U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman reflected during the symposium.

Pres. Clinton recounted that Albright had established herself on campus as a popular professor before he met her in 1988, on the presidential campaign trail for Michael Dukakis.

“By then, she’d already been at Georgetown six years, and she’d already been voted the best professor once, at least,” Pres. Clinton said. “I thought she was terrific. I just liked her.” Photo by Phil Humnicky/Georgetown University.

Photo by Phil Humnicky/Georgetown University.

When he won the presidency in 1992, he brought Albright on to help with the administrative transition, and appointed her as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations (UN).

Foreign service remains a male-dominated field, multiple speakers said, but much less so than decades ago. Albright was only the second woman to be appointed ambassador to the UN, and the first to become Secretary of State in 1997 at the start of Clinton’s second term. The symposium speakers, who were predominantly women, shared their experiences with the gender gap in diplomacy.

Mayu Ávila, El Salvador’s first female minister of foreign affairs, recounted the lack of gender diversity at the start of her and Albright’s diplomatic careers in the late 1990s.

At Ávila’s very first meeting at the UN headquarters in 1999, she stepped into a room full of men. “There were only nine women foreign ministers in the world,” Ávila recalled.

“There was no one else [in the meeting] but myself as a woman.” The meeting was held up by a male colleague who was late. When he had finally arrived, Ávila said, “He just turned around and looked at me and said, ‘Coffee with milk.’”

The crowd booed at the comment. Ávila went on to ask rhetorically, “What was a woman doing there in that very important meeting? Must be the waitress.” She explained that, while taken aback, she gave him the coffee, but sat right next to him and made the point of using her voice during the meeting, remembering the advice from Albright to always make yourself heard.

Ávila was joined by Tzipi Livni, former minister of foreign affairs of Israel, and Margot Wallström, former minister of foreign affairs of Sweden. All three women are current members of the Aspen Ministers Forum, which was founded by Albright in 2003 to strengthen diplomatic ties between the U.S. and Europe by increasing nonpartisan dialogue.

Wallström explained the motivation behind the “feminist foreign policy” concept that she, Albright, and other women diplomats adopted is not only progressive but rooted in concrete evidence. “Peace treaties that had women signing last longer,” Wallström explained during the panel. “More women mean more peace.”

“Promoting women is not the only right thing, it’s the smart thing,” Ávila said.

In her opening remarks for the second panel, Sherman shared a story Albright told her about her early years as the UN Ambassador. Albright arranged to meet the rest of the female ambassadors, and learned there were only 6 others, despite over 140 nations represented.

“Madeleine immediately formed the women into a caucus, of course, that they jokingly called the G7,” Sherman said.

“They all adopted an open-door policy with each other,” she continued. If a male colleague complained, “Madeleine suggested that he give his job to a woman, and then his nation, too, would enjoy the same benefit.”

Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the current ambassador to the UN and the next speaker, responded directly to this anecdote. She said she tried to do the same when she arrived at the UN, but only had the numbers for a ‘G5.’ When she told Albright she was disappointed that there were two fewer women, Albright remarked that she had seven across the UN, whereas Thomas-Greenfield had five in the 15-member Security Council alone.

Several of the speakers remembered Albright’s famed pins, which she collected and even wrote a book about their symbolism called “Read My Pins: Stories from a Diplomat’s Jewel Box”. Sec. Clinton, who discussed the pins in her recent documentary series with her daughter, “Gutsy,” said that they represented Albright’s interpretation of an important lesson in diplomacy.

“Even in the most serious negotiations, you’ve got to be able to make connections, but you also have to not take yourself so seriously that you can’t see yourself as others are seeing you, and your country, and your mission,” Sec. Clinton said.

Thomas-Greenfield, in the second panel, said that the lessons she learned from Albright have shaped and will continue to shape her career in foreign service.

“I’ll always have her as a pin on my shoulder.”