“Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu. A person is a person because of other people.”

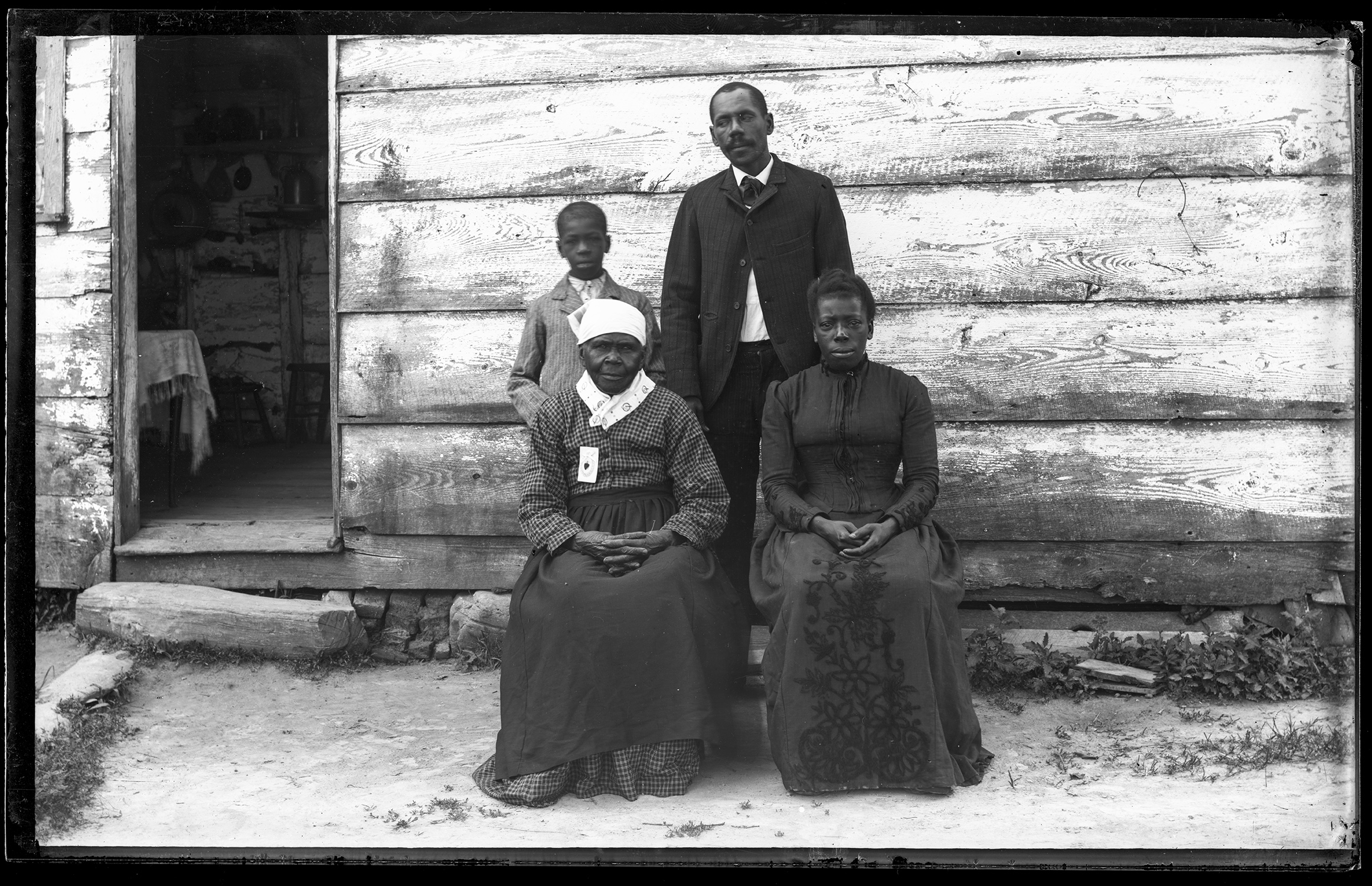

These were the words that Chase Chester (COL ‘22) chose to begin his informal remarks at a Feb. 7 gathering of descendants of Louisa Mahoney Mason, a woman who was enslaved by Jesuits at St. Inigoes, Maryland. Descendants of Mason, among them Chase Chester (COL ‘20), Henrietta Pike, Lynn Nehemiah, Evelyn Pike, and Mélisande Short-Colomb (COL ‘20) met at the Booth Family Center for Special Collections to view a newly-discovered photograph of Mason and celebrate her life, resilience, and family.

The photograph, which archivists at Woodstock Theological Library discovered in February, depicts Louisa Mahoney Mason, Robert Mason, her son, an unidentified woman, and an unidentified boy. It was taken sometime between 1890 and 1910 by Rev. John Brosan, confirming that the Mason family resided at St. Inigoes long after their emancipation. Although some archivists suspect that the second woman in the photograph is Robert Mason’s wife, Mary Mason, evidence suggests that she is Josephine Mason Barnes, who appears in a family photo belonging to Melissa Kemp, a descendant of Barnes’s. The young boy in the photograph remains unidentified.

According to an obituary published in St. Mary’s Beacon on July 22, 1909, Mason was born into slavery on St. Inigoes manor in May 1812 and died in July 1909 a free woman. Although her name is listed on the bill of sale from the Jesuit’s 1838 sale of over 272 enslaved people, also known as the GU272, Mason evaded the sale by hiding in the woods until the sale was complete. However, she remained enslaved until Maryland abolished slavery in 1864.

After the sale, Mason married a freeman by the name of Alex Mason. Mason’s obituary reported that they had six children together: Mary Ann (b. 1849), Charity (1851), Thomas (b. 1853), Daniel (b. 1853), Josephine (b. 1857), and Robert (b. 1859).

A few months before the outbreak of the civil war, Alex Mason was brutally murdered on the highway between St. Nicholas Church and St. Mary’s City, according to the obituary.

“A strange feature of this unfortunate affair was the entire absence of any rational cause that could have brought it about as Alex Mason was an excellent man and without enemies, and was too poor to excite suspicion that he had money on his person,” reads the obituary published in St. Mary’s Beacon.

However, a research paper published by Paul Rochford (COL ‘20), which can be found in the Georgetown slavery archive, found his murder to be probably racially motivated.

After Alex’s death, Louisa Mason remained an incredibly influential member of the St. Inigoes community, and Jesuits and community members alike relied on her for her excellent memory, calling on her to be an unofficial historian for the community. She maintained contact with the GU272 in Louisiana following the sale as well.

“She was remembered as a matriarch of her community, and her funeral was the largest, most diverse crowd from all the region,” Chester said. “And the writer of her obituary in the St Mary’s Beacon made a call to action for the community of St. Inigoes ‘to erect a monument to good Louisa Mason to perpetuate her virtues and show an appreciation of them.’”

On Feb. 7, members of the Mason family gathered on the fifth floor of Lauinger Library. The parents, aunts, uncles, and cousins greeted each other in front of the Booth Family archives, many meeting each other for the first time.

As members of the Mason family arrived, Lynn Nehemiah handed out flat wooden hearts for family members to write their names on and add to a family tree. She then laid three patterned orange scarves on the ground, on which she had written attributes exhibited by their ancestors.

Nehemiah also passed out blue folders, each containing a family tree that showed how everybody was related to Mason, a laminated copy of the obituary, and an essay written by a descendant who attended Georgetown Prep about his heritage.

“To have the opportunity to learn about my mother’s side of the family, and how faithful and respected my ancestors were not only by the Jesuits but the people of St. Mary, it truly brought joy to my heart,” Evelyn Pike, the third great-granddaughter of Mason, said after the fact. “I felt a bit overwhelmed, because I’m finding out such extraordinary information while also viewing the faces of my family for the first time.”

After the family members welcomed each other and talked, they held a 15-minute ceremony to honor the life of Mason and celebrate the reunion. The ceremony was originally to take place in the archives, but the key did not work, so it was instead held in front of the archive doors. Descendants took turns reading parts of Mason’s obituary, Chester gave his speech, and the family joined hands in prayer.

“It is said that the Georgetown administration believe that almost all the slaves that were sold in the 1838 sale died quickly of fever, then arrived in Louisiana,” Chester said during his speech. “Yet here we are and here we stand together in this room, actively living out our ancestor’s dream—that who were once torn apart hoped and prayed that one day their family would come back together.”

To end the ceremony, Nehemiah passed around the orange scarves, letting each person cut off a word to take home. Each family member left with a reminder of their ancestors and the work they did to keep the family together.

“In prior years, around the holidays, we grew to believe my mother had no family except for our uncle and we accepted that,” Pike said. “Meeting my cousins, and finding out how close we all lived, I was filled with comfort. I did not have that initial feeling of ‘this is a stranger.’ They felt familiar.”

After the ceremony, the descendants talked, took pictures, and looked at the artifacts in the display case, including parish records and other documents recording the history of slavery on campus. Mary Beth Corrigan, the curator for Georgetown’s Collections on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, was present to explain the different artifacts.

“The honor of Georgetown University recognizing and putting my family on display provides me with hope of change, clarity, and primarily motivation and excitement for years to come,” Pike said. “Harry, Anna, and all of our ancestors are excellent examples of bravery, courage, loyalty, and faith. And we thank them.”