Content warning: This article discusses gore, racial violence, and antisemitism.

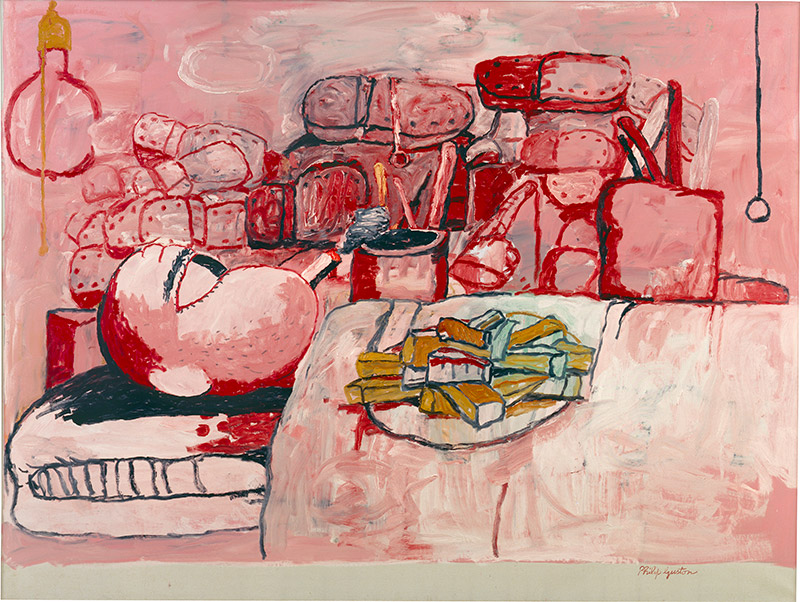

Disembodied arms and legs, masked figures, trash can lids, a cyclop’s eye—these are the components of Philip Guston’s symbolic language as his oeuvre maps decades of turmoil. Then there’s his distinctive, uneasy shade of pink,—reminiscent of raw meat, or a fresh wound, especially when paired next to harsh streaks of dark red—appearing most prominently in the cartoonish works he created in the latter half of his career.

The National Gallery of Art spotlights Guston’s expansive body of work in its special exhibition on display until Aug. 27. Aptly entitled Philip Guston Now, his work aims to process trauma in a world wracked by war, polarization, and racial hatred, which feels as eerily relevant today as it did decades ago when Guston worked during World War II, the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

The exhibition showcases Guston’s evolution of artistic style from dramatic mural compositions, to the dynamic splatters of color of abstract expressionism, to the stark cartoony forms of his later years—not to mention the thrilling variety of mediums, including large oil paintings, preparatory sketches, ink drawings, and studies for future murals.

Although Guston’s diverse body of work is intimidating at the first glance, the exhibition follows a linear format, guiding viewers through his distinctive eras, accompanied by rich biographical and historical context. Guston was born in Montreal in 1913 to a Russian-Jewish family that fled religious persecution in Ukraine at the turn of the century. In 1919, they moved to Los Angeles where Guston went to high school with Jackson Pollock, who would become one of the great abstract expressionists of the 20th century. The Guston family’s migration to Los Angeles occurred amid a surge in Ku Klux Klan membership; Los Angeles police destroyed an Anti-Klan mural Guston had created in 1933, a memory that permeates throughout his work in depictions of Klan violence and imagery. Guston, born Phillip Goldstein, eventually changed his name to conceal his Jewish identity.

Inspired by Mexican muralists such as Diego Rivera and artists of the Italian Renaissance, Guston’s early works are characterized by theatrical scenes with monumental figures. A particularly striking work is “Bombardment” (1937), which represents the bombing of the town Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Painted on a circular canvas, the figures seem to whirl out of a vortex, as the heart of the explosion spits flames at the center of the composition.

“If This Be Not I” (1945), painted during the final year of World War II, features a haunting, claustrophobic composition of children who seem to be in the midst of a theater production which has been inexplicably interrupted. Masked figures—a motif that appears throughout Guston’s work—represent the innocence of children at play in this painting, but gain a more sinister significance in other works: the masks raise the dilemma of the duty to bear witness to horrors and the agony of doing so. “It’s as if I want a mask,” Guston once observed of his work. “Art is a mask.”

The exhibit then leads you through Guston’s journey toward abstraction in the later years of World War II. It begins with a trio of dark red paintings created between the years 1947 and 1950, composed of claustrophobic, geometric forms interspersed with burning forms of cadmium red.

After seeing harrowing scenes of liberated concentration camps circulating in the media, Guston said, “I entered a very painful period when I’d lost what I had and had nowhere to go … Finally in 1947 or ’48, I dismantled everything and started from scratch.” And indeed he did. In 1949, he resettled in New York City and joined the circle of abstract expressionists that came to be known as The New York School, including Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, who rejected recognized forms in favor of visual representations of interior subconscious worlds.

You are then led down a hall showcasing the rest of Guston’s abstract works, the first of which are characterized by overlapping smudges of cheerful colors, such as coral pinks and tangerine, with dark and muted tones. In the paintings towards the end of the corridor, the bright colors are overwhelmed by expanses of gray where shadowy indications of a figure begin to emerge. Guston associated these works with “the golem, a humanlike being that, according to Jewish lore, was made from mud by a medieval rabbi and wielded great powers of both good and evil”

It was a delight to view these large paintings in person to get a proper sense of their scale and presence, as well as to get an intimate look at Guston’s dynamic brushwork and thick impasto.

In the late ’60s, in a nation torn apart by stark polarization, Guston too felt divided—but his division was between his competing impulses of figuration and abstraction, as he began to feel that abstraction failed to bear witness to the violence and turmoil spiraling around him. In this period, Guston began to paint everyday objects—coffee mugs, windows, clocks, books—in a distinctive cartoonish style, characterized by bold lines and cacophonous colors. This method would endure for the rest of his career.

While Guston’s depictions of everyday objects were innocuous, he also used this cartoonish style to explore darker themes and satirize evil in a way that makes it impossible to look away from. One series of paintings shows figures in white hoods—Guston’s symbol of evil—as they drive to the edge of town or smoke cigars in living rooms and they go about their ordinary lives, evoking the ubiquity of klansmen in American society.

One of these paintings, “The Studio” (1969) portrays one of the hooded figures as an artist in the act of painting a self-portrait. This painting reflects Guston’s anxieties of his own complicity in the face of injustices he had witnessed, and raises uncomfortable questions about his responsibility and privilege as an artist. “They are self-portraits,” Guston said. “I perceive myself as being behind the hood.” Guston’s work tracks an artistic mind that is acutely, often cripplingly, self-aware. He constantly questioned himself and his purpose as an artist, as well as the role he plays in an increasingly nonsensical world.

Among the array of objects that recurred in Guston’s later period, the image of disembodied legs is the most striking: tangled together, knobby-kneed, and in Guston’s signature hues of red and pink. This was likely inspired by Guston’s brother Nat, who had died decades earlier when his car rolled over backwards and crushed his legs.

In the exhibition’s final stretch, there hangs a work titled “Reverse” (1979) in which the backside of a canvas is painted in a position leaning against a wall—is it a work in progress? Or a work from a previous era long forgotten? It is a fitting end to an exhibition celebrating an artist in a constant state of evolution and reinvention, one without a fixed visual language. This expansive retrospective of Philip Guston reminds viewers that although paintings hang static on the wall, art is in a constant state of flux as it interacts, permeates, and reflects the turbulent world roaring around it.

Thank you for sharing this insightful comment on the Philip Guston exhibition. It’s fascinating to see how Guston’s symbolic language and distinctive use of color, particularly the unsettling shade of pink, serve as powerful vehicles for conveying his exploration of trauma and societal issues. Discover More Here how it could be translated to another people. The inclusion of his early works inspired by Mexican muralists and the Italian Renaissance, as well as his later abstract and cartoonish pieces, showcases the breadth of his artistic range.