Eiichiro Oda took 26 years to write and illustrate One Piece. Had I read the whole thing in one sitting, without eating or sleeping, it would only have taken me just over a week, but I still had a life to live. So, given its 1091 chapters and counting, I would consider the eight months it took me to read it a reasonable amount of time.

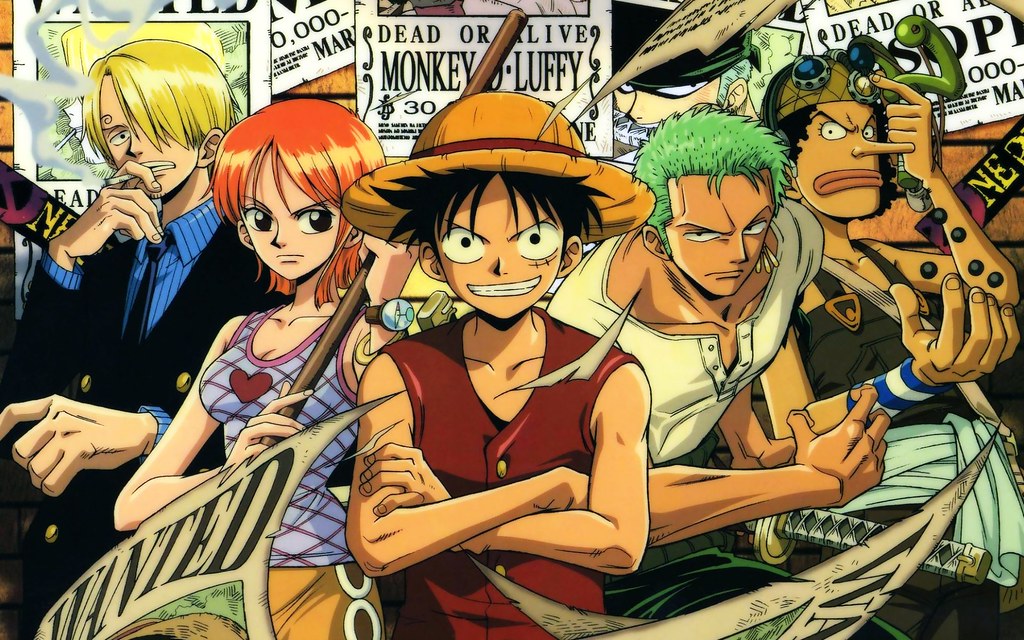

One Piece is a manga about Luffy, a boy made out of rubber, who decides he will claim the titular “One Piece” treasure and name himself King of the Pirates. Throughout his journey, Luffy assembles a motley crew vested with different specialties and superpowers. One Piece’s fictional universe is rich with its own geography, cultures, lore, and magic, and yet, what struck me the most was a message that Oda had not intended to convey: lessons on the complexity of trans identity and the position of queer identities in society.

There has been much debate on the prevalence of queerness in One Piece. While some think the representation is meaningful, others see aspects of it as highly problematic. Furthermore, many of these analyses come from a Western perspective that the author—a heterosexual, cis, Japanese man—does not share. This difference in culture might imply that Oda’s nuanced representation of trans people is entirely incidental. However, when a reader absorbs media, the author is not present to contextualize their work and tell the reader what messages they intended to portray. Even if unintentional, the messages about transness that are found by queer readers in the West, such as ourselves, undeniably remain.

When discussing the problematic nature of One Piece’s depictions of trans people, people often point to one character right away: Bon Clay.

Bon Clay is the first gender non-conforming character the reader encounters. His eccentric look—puffy pants, swan-adorned coat, and ballet shoes paired with hairy legs and clownish makeup—originally had me questioning whether his portrayal was transphobic. However, it soon became clear that Bon Clay exists as a powerful condemnation of gender essentialism.

Gender essentialism is the idea that gender is discrete and biologically determined. In other words, one can only be the gender they were assigned at birth and must either be male or female, but not both. From Bon Clay’s first introduction, it is clear that his character deliberately blurs those lines. Bon Clay is an officer in a crime syndicate which embodies gender essentialism. Every level of the syndicate contains one male officer, whose code name is a number, and one female officer, whose code name is a holiday. Bon Clay, however, refuses a partner and adopts both code names, dubbing himself as both Mr. 2 and Bon Clay—the latter being a reference to a Japanese festival. He is powerfully subverting the rigid gender roles of the organization he is a part of, forging his own path.

Bon Clay’s rejection of gender essentialism highlights that he is actually a liberating depiction of trans people. He highlights that trans people do not have to be categorized, nor do they have to live within a binary determined at birth. They can transcend strict gender categories in any way they feel is comfortable.

Two other characters, Kiku and Yamato, also embody the nuances of trans identity.

Kiku is a trans woman who lives in Wano, an isolated island that Luffy and his crew visit during their travels. She is a retainer for the former Shogun of Wano, a job which she held before her transition. The way her colleagues treat her, however, signifies how trans people deserve equal respect. Kiku’s fellow warriors respect her and continue to value her strength. None of them misgender her or out her to others, giving her the control of who knows that she was assigned a different gender at birth. Furthermore, she does not have to forfeit any of her passions to transition. Despite samurai being a strictly male position, Kiku retains the title and her role as a freedom fighter after her transition. This is comforting as it indicates that trans people do not need to lose anything they like when they transition.

An interesting parallel to Kiku, however, is Yamato. Yamato is a trans man who continues to present as femme. He maintains long hair and wears a tightfitting top, making no attempt to hide his large breasts. Though there is a lot of confusion about Yamato’s gender when the characters first meet him, he clarifies that he identifies as a man. The characters immediately accept his identity, and when it is time for them to bathe in the gender-segregated hot springs, Yamato bathes with the men (whereas Kiku soaks with the women).

Despite his gender presentation, the characters accept Yamato as a man. Yamato clearly symbolizes a concept underappreciated in the media: gender presentation does not equal gender identity. Trans men do not have to forsake femininity to be valid as men. The declaration of their identity is enough to merit respect and recognition for their gender.

Another important example of a trans character is Emporio Ivankov. It is this character who presents the readers with another nuanced, and oft ignored, message about trans identities: the importance of queer joy.

As one of the Revolutionary Army’s founders, Ivankov is imprisoned in Impel Down, the fascist World Government’s high security prison. He and his followers, however, live on Secret Level 5.5, also known as Newkama Land, a floor of the prison they covertly constructed.

Ivankov is a clear homage to Frank N. Furter of Rocky Horror Picture Show fame. The twist: his superpower is the ability to control the hormones within people’s bodies. He uses this power to heal, to give people energy boosts, or even to change someone’s sex, with the latter being used most often.

Within the prison, Ivankov and his followers constantly switch between genders. In Chapter 537, he sings “Man or woman or both, be whatever you want to be!! I’ve already shattered the borders of gender! We all have! We’ve already transcended it! We are the new Humans—the New Kama! And this is our garden of freedom.” The cheers of the crowd highlight the joyful spirits of Ivankov’s people. They are free to choose their genders and embrace their most authentic lives. Their contentment with their transitions demonstrate radical trans joy—something that other media depictions of transness often lack.

Ivankov is a symbol of hope and freedom from oppressive gender roles and stereotypes—a representation of the joy that can accompany transition. This narrative is one that is hard to come by when much of the reporting on trans issues today emphasizes detransitioners, people who return to their gender assigned at birth after transitioning. This constant media focus on detransitioning misrepresents the issue since only one percent of all those who transition experience regret. Rather than continue the narrative that trans individuals will regret their transition, One Piece celebrates the joys of transitioning with characters like Ivankov.

Ivankov, alongside the other trans characters, represents a vital message about how trans identities fit within our own society. Ivankov and others work against the fascist and colonial structures dominating One Piece’s fictional world, highlighting how, despite the marginalization of trans identities by embedded societal institutions, transness is inherently revolutionary.

Much like the real world, One Piece’s prison disproportionately imprisons queer characters, including Ivankov, Bon Clay, and the trans inhabitants of Secret Level 5.5. The queer prisoners of Impel Down, however, subverted the prison’s—and by extension the World Government’s—oppressive structure. The inhabitants of Newkama Land built Secret Level 5.5 without tipping off the prison guards, thereby creating a raucous queer utopia right under the World Government’s nose. Furthermore, despite living in a bleak environment like a prison, the inhabitants of Secret Level 5.5 make no attempts to escape until they are exposed. Thus, they undermine the very purpose of the prison and show the rebellious nature of their queerness. Ivankov is also a leader of the Revolutionary Army, recruiting the vast majority of Level 5.5’s residents to join the cause, thus situating queerness as inherently insurrectionary.

A similar idea is explored on Wano, the island where Kiku and Yamato live. During his stay on the island, Luffy and his crew attempt to overthrow the oppressive Social Darwinist, Kaido, who has taken control of the isolated nation. Kaido’s siege of the island nation parallels it to real world colonialism as its natural resources are extracted and regions of it become cogs in a global weapons manufacturing ring. By fighting Kaido’s regime, Kiku and Yamato show, more overtly than ever before, how queerness is in opposition to oppressive institutions like colonialism.

In our real world, queerness has been situated in a similar manner. Indigenous genders and sexualities have always defied colonial definition and understanding, making their very existence anti-colonial. Further, fascism necessitates conformity which queer people are not due to the way they challenge heteronormativity. Fascist regimes have also kept queerness out of the cultural norm because queer couples often do not engage in reproductive sex, thus slowing the production of a compliant populace. Thus, any queer persons intrinsically resist fascist powers. One Piece’s positioning of queer characters as freedom fighters repeats this truth and echoes the lessons of people like Amelio Robles, a trans man who fought in the Mexican Revolution.

Though One Piece takes place in a fictional world, its queer characters and their sociopolitical standings within the world represent many realities about queerness. The characters teach us truths about how we ought to treat trans people and the joyfulness of their lives. They play key roles in revolutionary, anti-fascist, and anti-colonial movements which highlight the innately radical nature of queerness. The fact these messages were unintentional or that not everyone will pick up on them matters not because—to a small fraction of the manga’s readers—One Piece is a meaningful reflection of queerness today.

Awesome article, very well explained.