Content warning: This article discusses self-harm and addiction.

In the spring of 1980, President Jimmy Carter announced that the U.S. would boycott the Summer Olympic Games in Moscow that year to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The unprecedented action not only dashed hundreds of competitors’ dreams, but it evidenced the deeply American association between athletics and ideals. The field, the court, and the ring are all sites of transference for the American principle of pulling oneself up by the bootstraps and succeeding on one’s own virtue—myths reinvigorated by Cold War-era patriotism as hallmarks of democracy. The Olympic games are an opportunity for the international community to square up against one another off the battlefield and outside of summits. Carter’s Olympic boycott proved that the U.S. would champion democracy not just through politics and economics, but through its cultural customs, too.

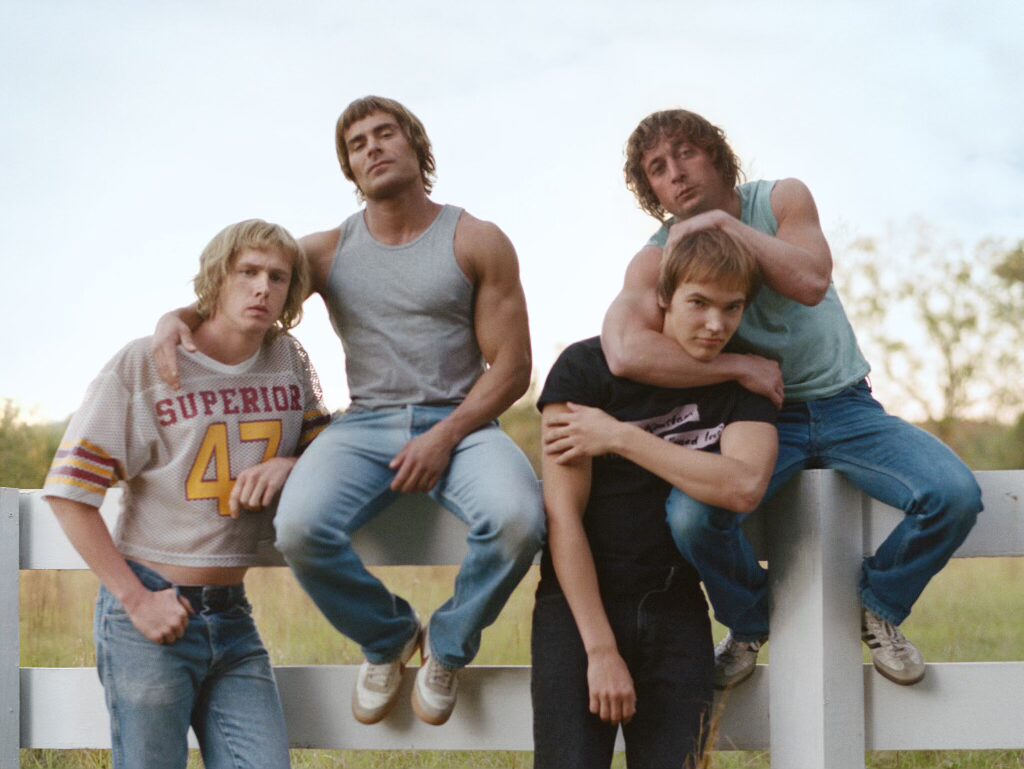

Just as the Olympics are not only about athletics, writer-director Sean Durkin’s The Iron Claw (2023) is not solely about wrestling; it’s the WWE of sports movies, using visual appeal and a talented ensemble as a smokescreen for the evil festering underneath. It’s a biopic about the Von Erichs, legendary brothers who followed in their father’s footsteps and rose to American wrestling fame at the end of Carter’s presidency into ’80s; but it’s also a familiar story about exploitation disguised as patriotism and toxic masculinity touted as patriarchal duty—values heavily emphasized as the U.S. tried to out-macho the Soviets. In this biting exposé of the American entertainment industry, Zac Efron, Lily James, and their up-and-coming co-stars Jeremy Allen White and Harris Dickinson cement their places among the Hollywood greats with poignant performances of Durkin’s stunningly devastating screenplay.

The intrigue surrounding the Von Erichs stems from the so-called “curse” that plagued them with incessant tragedy including the death of Jack “Fritz” Von Erich’s (Holt McCallany) first son when he was a young boy. Within the first few scenes, though, Durkin debunks the myth to pinpoint the true source of the rest of the family’s misfortune: The pressure and exploitation to which the brothers were subjected, starting with their father’s conditioning.

The opening sequence takes us to a National Wrestling Association (NWA) match in 1963, where Fritz defeats his opponent with his signature move, the “Iron Claw”—a crushing grip around the head that brings three-hundred-pound men to their knees. Brothers Kevin and David, portrayed by children in this first scene, watch as their father performs for a cheering crowd and then promises his wife that he’ll win the NWA Championship, instilling in them the expectation of performing masculinity through physical strength and breadwinning. Filmed in monochrome as a 1963 TV program would be, The Iron Claw’s opening ingeniously establishes its film-within-a-film: We watch the so-called “Von Erich Curse” unfold like the American public did decades ago in this scathing reproach of the entertainment industry’s willingness to capitalize on real people’s tragedies.

Like his opponents, Fritz suffocates his sons in an unyielding grip, offering them conditional love in exchange for their commitment to the sport, and ultimately their lives. David (Dickinson), Mike (Stanley Simons), and Kerry (White) all die because their involvement with wrestling wreaked irreparable damage on their mental and physical constitutions—the latter two died by suicide. Durkin tactfully spares the boys’ deaths the savage exhibitionism of their fights, giving them the privacy and respect they weren’t afforded in real life or in the ring.

The film jumps to 1979 as Kevin (Efron), heavyweight champ of the Texas NWA, accelerates toward becoming World Champion. We get the lay of the land in the Von Erich household when, around the breakfast table, Fritz tells brothers Kevin, David, and Mike the “ranking” of his four sons in order from favorite to least—unsurprisingly, it’s also the order from most wrestling prowess to least. On top is Kerry, who is currently off training for the 1980 Summer Olympics; at the bottom is Mike, the scrawny youngest brother who wants nothing to do with the sport (or any sport, for that matter); and middling are Kevin and David, the eldest brothers, both rising to NWA prominence. He reassures them that the “rankings can always change,” though, and his wife Doris (Maura Tierney) sits in complicit silence, effectively sealing the boys’ fate to put their minds and bodies through endless turmoil and familial competition for their parents’ affection.

Each tragedy brings the remaining brothers closer, with Kevin and Kerry seemingly inseparable by the end. White’s Kerry is not unlike his Golden Globe-winning Carmy of the TV series The Bear: stoically tortured, yet undeniably sympathetic. He and Efron subtly infuse depth into their muscleman characters with glances cast downward or clenches of the jaw curbing tears. In a phone call on the morning of Kerry’s death, the younger brother confesses to Kevin that addiction and loss are chipping away at him and he feels utterly alone. The palpable silence that hangs in the air as the older brother searches for the perfect, life-saving words encapsulates the immeasurable weight they’ve shouldered all their lives, unable to admit its crippling effects for fear of being called weak or unmanly.

It’s a never-ending toil for the young men, as being the biggest or the best isn’t enough to succeed—you have to act the part outside the ring, too. Since NWA and WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) matches are premeditated and choreographed, you don’t need to win the most fights to become World Champion, rather you have to be anointed by the league; The Iron Claw details the inner-workings of the NWA to expose that the fighting is solely for spectacle. Consequently, fighters’ star quality was integral to selecting who to promote, which Kevin learns the hard way during his ascent in the ’80s. When filming a promotional video at the World Class Championship Wrestling (WCCW) TV station, Kevin stumbles over his words and apathetically regurgitates half-baked threats at his opponents while younger brother David snickers from behind the camera. Efron sympathetically portrays the meathead with a heart of gold while Dickinson’s David shines as the charismatic, camera-ready golden boy, effortlessly usurping the spotlight. As WCCW president, Fritz had orchestrated Kevin’s media circus, but seeing David’s potential, he re-orders the ranking and turns his resources toward his underdog son, simultaneously sparing and depriving Kevin of his attention in a biting revelation of conditional love and its consequences.

Television remains omnipresent for the Von Erichs as both actors and viewers, threatening to make or break their careers; the whole family watches with an eerie stillness as President Carter announces the 1980 Olympic boycott, sending Kerry packing from the training camp. Upon his return, Kerry teams up with David and Kevin to compete in three-on-three “tag team” matches. Their chemistry radiates out of the screen in a breakneck montage of the speedo-clad brothers performing roundhouse kicks and aerial dives in perfect unison—a feat for the actors and choreographers alike. You can’t help but root for them as their mullets sway to and fro and their chiseled bodies soar through the air. Durkin omits no gory details in any of the film’s many fights, inundating us with brutality to the point of numbness and expertly implicating us in the sensationalization of violence. We see the fighters’ names and weights emblazoned on the screen, we hear the announcers’ commentary, and we wince at every blow to the face—it’s as if we were watching live from our sofas.

The real villain of Durkin’s tale, then, is not Fritz or the NWA, but what they symbolize: A hyper-masculine ideology that pushes boys and men to the brink, making perfect fodder for the American entertainment industry. In the vein of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie released in July, The Iron Claw offers a searing interrogation of how patriarchal pressures damage male psyches, counterintuitive as it may seem. Although not revolutionary in sentiment, its deeply affecting screenplay and performances carry the emotional labor.

In the final scene, Kevin watches his young sons tossing around a football and begins to sob when he admits, “I used to be a brother.” His boys hug him and reassure him that it’s okay to cry, then invite him to play ball with them. It’s a rare tender—if saccharine—moment of unfettered familial love, putting an end to decades of patrilineal trauma and abuse. Seeing the chisel-jawed Efron weep after Durkin’s two-hour-long rebuke of toxic masculinity is a touching endnote; but it also serves as a reminder that beneath the abs and satin robes are real people whose humanity America will readily excavate for a dime.

In the final scene, Kevin watches his young sons tossing around a football and begins to sob when he admits, “I used to be a brother.” His boys hug him and reassure him that it’s okay to cry, then invite him to play ball with them. It’s a rare tender—if saccharine—moment of unfettered familial love, putting an end to decades of patrilineal trauma and abuse. Seeing the chisel-jawed Efron weep after Durkin’s two-hour-long rebuke of toxic masculinity is a touching endnote; but it also serves as a reminder that beneath the abs and satin robes are real people whose humanity America will readily excavate for a dime.