Sweat drips, sneakers squeak, men’s torsos glisten, and heads bop side-to-side as a hypnotic techno beat makes your heart pound in your ears—all that’s missing is Donna Summer crooning “I Feel Love” in the background. No, it’s not a gay club in 1985 New York, but the Phil’s Tire Town Tennis Challenger in New Rochelle, NY. Set in 2019, Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers (2024) masquerades as a tennis epic, but is steeped in sex, queer iconography, and arguably, love. Somehow, the Call Me By Your Name (2017) director has upped the ante of fiery gay passion, creating a tense, steamy romance discernible only to the trained (read: gay) eye. Throw into the mix a show-stopping female protagonist, and you have Challengers—a film whose core narrative really takes place off the tennis court.

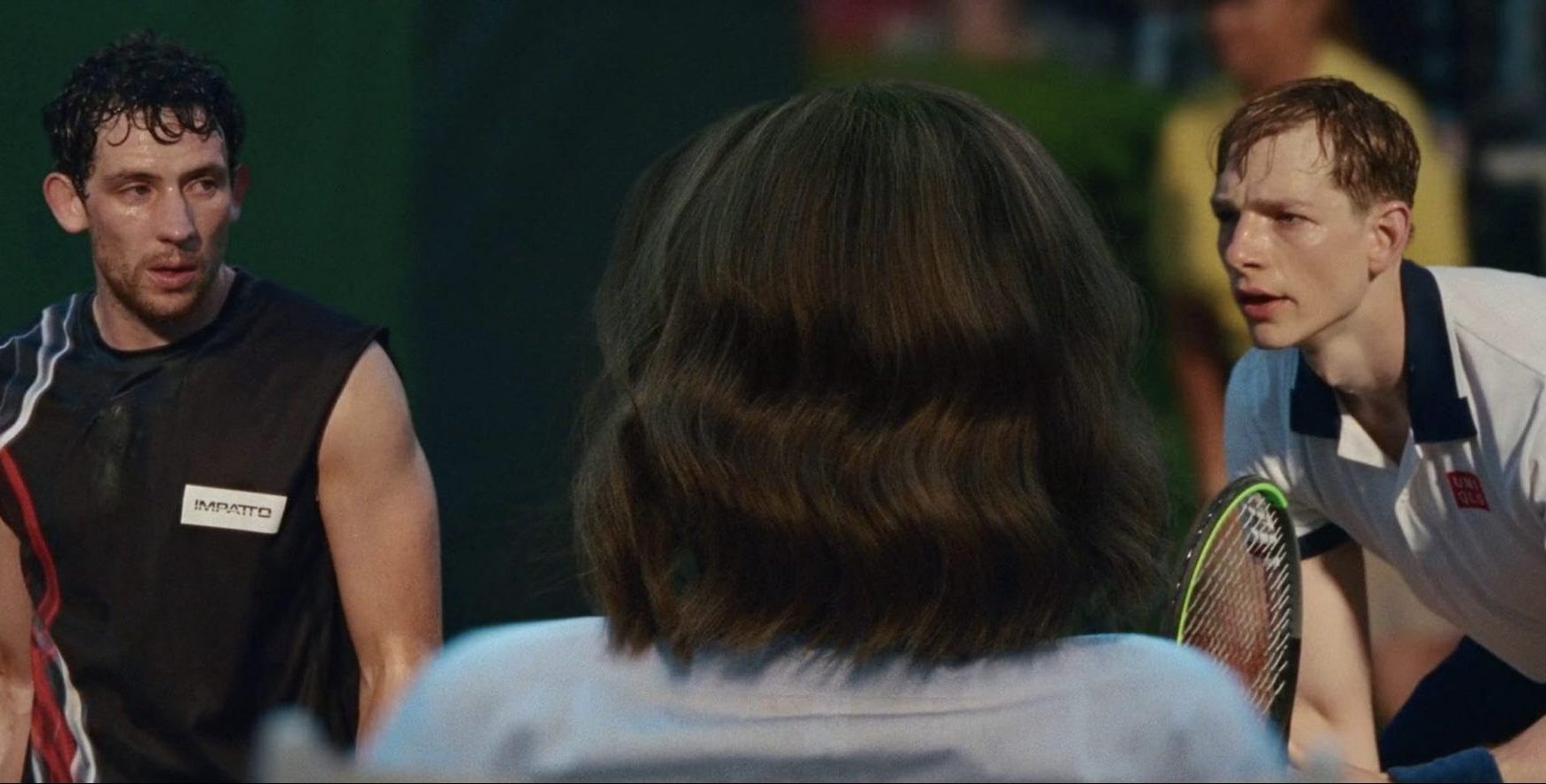

The opening scene brings us to the heated New Rochelle challenger match between Art Donaldson (Mike Faist) and Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor) as Tashi Donaldson (Zendaya)—neé Duncan—sits in the center of the bleachers, perfectly aligned with the net dividing the court down the middle. Spectators’ heads turn rapidly with the ball’s volleys, but Tashi’s moves at her own pace, tracking the players, not the game. It’s a perfect introduction to the dynamic between the central trio, comprised of the tennis pros who harbor love-hate relationships with one another and the sport.

This late-career match remains a touchpoint throughout the movie, as flashbacks to various times in their lives unravel a convoluted backstory. Art and Patrick, now opponents, were once doubles partners, sharing a seemingly iron-clad friendship forged in their boarding school dorm room; that is, until the 18-year-old boys watch Tashi play for the first time, instantaneously succumbing to utter infatuation with the U.S. Open Juniors’ Champion. Naturally, the boys agree to play against each other for her phone number. Everyone knows that Art, the sweetheart with a blond mop of hair, doesn’t stand a chance against Patrick, the passionate, hot-headed bad boy. But the Zweig-Duncan whirlwind sexcapade implodes when Tashi suffers a career-ending knee injury in her first year playing for Stanford, and teammate Art swoops in to help her rehabilitate while Patrick tries going pro. Even still, well into her marriage to Art and their professional coach-player relationship, it’s clear that the boys’ competition for Tashi’s affection never truly ended. Withholding yet sympathetic, Zendaya expertly communicates her character’s competing desires and self-destructive ambition. No matter how fiery things get between the guys, Zendaya maintains command of the screen, giving us a multifaceted athlete, mother, and partner whom we sometimes hate to love.

The triad’s very first conversation establishes the film’s euphemistic use of tennis as a substitute for sex, allowing Guadagnino to surreptitiously spin a complex web of queer romance. Perched on a rock shoreside, waves crashing behind her and a pearly full moon illuminating her silhouette, Tashi uses her siren-like allure to reel the teenage boys in as they lounge in beach recliners with cigarettes hanging off their lips. She tells them that they “don’t know what tennis is…it’s a relationship”; but while Tashi plays singles, Art and Patrick have always been the “Fire and Ice” duo on and off the court. Patrick later recounts to Tashi that he taught Art how to masturbate—and on a trip to Stanford the following year, the former roommates rather intimately share a churro, taking alternating bites while holding eye contact and brushing sugar off each other’s cheeks. Phallic imagery coupled with explicit—if restrained—sexual encounters fill the film with seemingly innocuous moments that somehow still leave the audience blushing. Faist’s endearing portrayal of the sweet golden boy Art brilliantly complements O’Connor’s devilishly coy Patrick, building tangible sexual tension through every shared glance. Guadagnino makes us feel like we’re intruding in these moments—a masterful manipulation of lust, ambition, love, and rage that confronts us with the real (if, at times, aggravating) variability of complex relationships.

But like Tashi with her “two little white boys,” Guadagnino loves to tease us. Stolen moments and heated tennis matches are not an add-on to the sex teased by the film’s promotion, but are wholly a substitute. In the trailer, Guadagnino’s intensely sensual remix of Eurythmics’s ’80s anthem “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” paired with a glimpse of the hotel scene, seems to promise some three-way action—but we never get more than a kiss. There’s only one moment of on-screen physical intimacy between the men, and nothing that the trailer doesn’t spoil; what’s more, successive scenes of intimacy are intensely unsexy, and filled with Freudian confusion as Tashi maintains her siren-like control over the boys. Guadagnino toys with us, promising some release of the sexual tension that steadily builds throughout the film, but it never comes—at least not explicitly.

Ironically, by substituting intercourse with tennis innuendo, Guadagnino suggests that the men share a love founded upon something much deeper than sex: companionship. Meanwhile, Tashi only engages in relationships for sport—and she plays alone. The egotistical Patrick wants her validation, the sensitive Art wants her affection, and the driven Tashi denies both, playing a never-ending match as she bounces between them. The cycle is toxic, codependent, and unbreakable—a powder keg viewers couldn’t pry their eyes away from if they tried.

What Guadagnino spares in the bedroom, he gives us in spades on the court. Echoing a conversation between Patrick and Tashi, viewers are forced to ask during these matches, “Are we still talking about tennis?” We play right into Guadagnino’s hand, increasingly struggling to pinpoint the specific source of the players’ adrenaline, and consequently, our own. Before the studio logos even roll, we are gifted with a riveting, tense, and sexy montage of close-ups from the film’s pivotal tennis match. Beads of sweat drip from Art’s face as he stares us down, racket poised in the background ready to strike; the camera then cuts to Patrick, grimacing and staring up at his opponent, the predator to Art’s prey; Tashi’s eyes squint as her mouth opens in some exclamation beneath the frame.When the heart-pounding house beat kicks in mere minutes into the movie, and the camera flies down from an aerial shot of the court to place Zendaya’s stony face front and center, what could be a boring and sweaty sports match becomes a palpable phenomenon.

As we climatically return to the match point at the end of the film, Guadagnino’s mastery of cinematic form is made abundantly clear. Flashing between differing POVs, the audience dizzyingly becomes the ball, flying between Pat and Art— their sensual groans echoing in our ears—before the camera moves under the court, watching the men play from beneath their feet. Guadagnino achieves a similar effect in the less-obviously intense moments, with quick-cut close-ups and off-kilter shots that make us feel like an intruder on some deeply private moments. When the sweat drips from Art’s face onto the camera as it gazes up at him from his crotch height, or Tashi screams her near-orgasmic cry in a slow motion close-up, the sensuality and sexiness of Guadagnino’s creative choices crystalizes. The theater experience keeps the blood pumping for all 131 minutes, blending the tennis with the not-tennis, companionship with romance, and competitive athleticism with carnal passion.

Although it’s effective, the sports metaphor may instill a sense of frustration with Guadagnino’s decision to relegate a gay love story solely to teasing; why would the Call Me By Your Name director now shy away from overtly representing queer romance on the big screen? Is Challengers merely queerbaiting us with two closeted men who express their love to each other through tennis and churro-biting and smirks? Maybe not. Art, Pat, and Tashi are all deeply repressed and egotistical individuals, whose glamorous facade hides the incredibly unhealthy rivalry and competition around which they build their lives and self-worth. The dynamics of elite-level sports portrayed on screen undermine any possibility of aspirational romance or emotional fulfillment. Watching Challengers, I can’t help but be glad to have quit tennis at age 12. Who knows, maybe I would have been the next Art Donaldson—but I think Guadagnino invites us all to be relieved that we aren’t.