TW: Mentions of drug-use and traumatic events

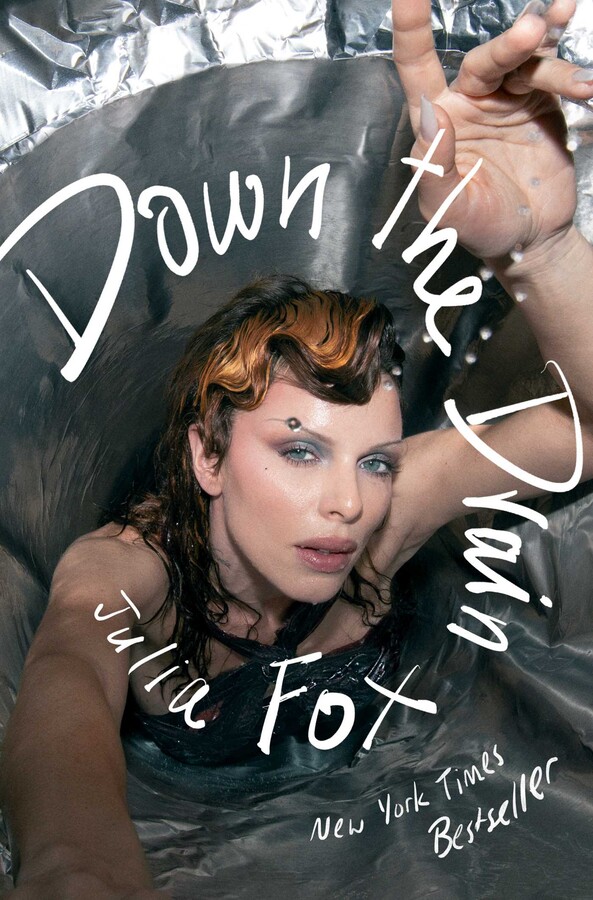

When I set out to read Julia Fox’s memoir, Down the Drain (2023), I expected nothing less than pure, unhinged entertainment. With a deliciously stacked resume as a former dominatrix, resident New York party-girl, and pioneer of “messy celebrities,” I assumed Fox could floor me by describing her version of an average Tuesday. While there were many sentences which made me triple check that I had just read the right thing, the most shocking thing about Fox’s story is her nonchalance in its retelling. Yet, Fox’s narrative is anything but stale.

Fox’s memoir begins with the retelling of her youth, where her penchant for mayhem takes root. Left alone in New York by her absentee parents with the uninhibited impulse of an adolescent mind, Fox found herself navigating the city’s seedy underbelly and regularly engaging in activities extreme for most adults. At age 12, she got into regular altercations with the cops. At 17, she began working as a dominatrix. By her 18th birthday, her inner circle resembled a drug cartel and she was shooting up heroin with the casual delight of eating a candy bar.

Despite the shocking nature of her teenage years, Fox flings each volatile event over her shoulder like a Birken bag, strutting off to the next flaming disaster with little hindsight. Often, her subdued reflections feel misaligned with the nature of the stories she recounts. During the peak of a blatantly abusive relationship with her drug-dealing boyfriend, Ace, Fox grieves like any teenage girl would over a difficult boyfriend. She laments that her “clothes no longer fit” and her “once clear complexion is now speckled with zits.” Later, Fox takes his call from rehab and rolls her eyes as he grovels, commenting on his obsessive nature with an overt sense of frivolity.

At first, Fox’s nonchalance reads as entertaining to the point of feeling forced. It felt as if Fox played too much into her chaotic caricature and neglected to consider the importance of emotional vulnerability. On multiple occasions she recounts one of her harrowing overdoses by dancing over it in the span of three sentences before scurrying right onto the next club in her seemingly never ending night-out. And perhaps that kind of reckless indifference is exactly what we should expect from Julia Fox—a woman who made a career out of daring spontaneity (see: Fox wearing an outfit made entirely of condoms); at some point it becomes hard to believe that even an overdose could seem so pedestrian.

Fox’s openness around these traumatic events coupled with her refusal to reveal any raw emotions is rather perplexing to the young reader. Most Gen-Zers have grown up in a rather transparent generation, especially with issues pertaining to mental health. With the extreme honesty exhibited in her memoir, I had expected Fox’s memoir to read as a mature and honest reflection. While she certainly did not hold back when it came to the raw and gritty, her lack of emotional perspective was uniquely striking—the single sentence dedicated to her overdose kept me thinking longer than if I read an entire chapter dedicated to it. My emotional attachment to such apathy begged the question: at what point does honesty lose its impact?

Fox toes the line between destigmatizing her experiences and normalizing them to the point of dilution. However, this uncanny valley in the realm of authenticity is not to the detriment of Fox’s work. If anything, this cognitive dissonance stands as a necessary component of her memoir; it triggers a greater reflection of the societal urge to heal oneself and find comfort in “being okay.” As online norms have shifted to expect honesty regarding hardships rather than hiding behind perfectly curated sunset vacations, people’s most personal issues become just another photo-dump in the algorithm. Soon, photo-shopped bikini pics brush up against eating-disorder recovery videos and desensitization inevitably follows suit.

I cannot say whether Fox’s casual manner of relaying trauma was intentional or not. On a stylistic level, I didn’t always agree with her detached tone choice; it streamlined the events of her life onto one emotional plane which at times took away from her dynamic story. However, Fox’s celebrity image was the perfect medium to employ this seemingly negligent style of writing in a meaningful way. Celebrities naturally have a split public and private persona, but Fox’s are intimately intertwined. Because her opportunities largely came from the money she got from sex-work or people she got addicted to drugs with, relishing in her successes means directly facing the traumas that brought her to them. Yet, for the majority of the book, Fox resists doing so; instead she dissolves these experiences into her persona to a point beyond confrontation.

Though having an internet presence is not enough to classify rank-and-file folk as celebrities, almost anyone who has a social media account understands the eerie feeling of being publicly observed. We may not notice it, but by making vulnerability a public conversation, we lose the ability to privatize, and therefore, authentically process our own emotions. Fox’s style presents the reader with an extreme version of what happens when the personal and the private conflate. Her transparency does not read as reflective, but completely detached; a cognitive dissonance so extreme that the reader cannot help but pick up on it, even if we are at first entertained. Despite the prevalence of raw transparency online, Fox’s glaring normalization of trauma, largely due to her lack of reckoning with her past, forces us to reckon with our understanding of struggles we claimed to be so aware of.

Ultimately, Fox refused to spin every personal tragedy into the juicy gossip that is expected from her.. At the peak of her career during the filming of “Uncut Gems,” her first major film role, we expect to find Fox relishing in the fame she had been chasing; instead, we find Fox at her lowest point: coping with the loss of her closest friends, both to overdosing on a drug she still can’t seem to quit. The memoir ends in this place of unresolved grief, contradicting many expectations I had for a celebrity memoir, which usually end with the “I made it” moment. Fox’s ending feels unfinished and even leaves the reader feeling slightly unfulfilled. Perhaps Fox’s vulnerability was never really meant for anyone but herself.

No matter how much we normalize conversations around trauma, we can hardly expect to fully understand and control it. Fox’s memoir proves that exact sentiment: she’s incredibly open about her demons and consistently attempts to portray them as natural to her life, only for her to conclude the memoir more uncertain than when she began it. The book proves to be an insidious demonstration on our current and largely misunderstood perception of trauma. Just because our “online selves” and those we share with feel comfortably acquainted with pain— or the content that depicts it— does not mean that we should be.

Though Fox’s memoir came out a little under a year ago, she remains a cultural icon, especially with the rise of Charli XCX’s album BRAT (2024). In one of the album’s lead singles, “360,” Charli personally cites Fox, boasting that she’s “so Julia.” According to Charli, Julia truly embodies the “BRAT-girl summer”—a glamorized persona of brutal honesty and unabashedness that everyone seems to be aspiring towards. Yet, people are quick to forget what that exactly entails. Fox straightens out the raw, chaotic, and traumatic reality of what it means to be “so Julia” in her memoir. Down the Drain, though certainly jarring, pushes a sentiment to redefine authenticity. Sometimes, the most honest emotion can be uncertainty: a mixture of feelings, unexplored and candidly messy.