One of Georgetown’s newest classes, Race, Power, and Justice at Georgetown, has been in the works for almost a decade. Now, as the fall semester progresses, the six-week long, one-credit course is officially running as a graduation requirement for all students, starting with the class of 2028.

It aims to tell Georgetown’s history “in relation to its neighbors, the United States and world,” according to the Office of the Provost’s website. The class routinely features guest speakers to question how race, power, and justice have functioned at the university.

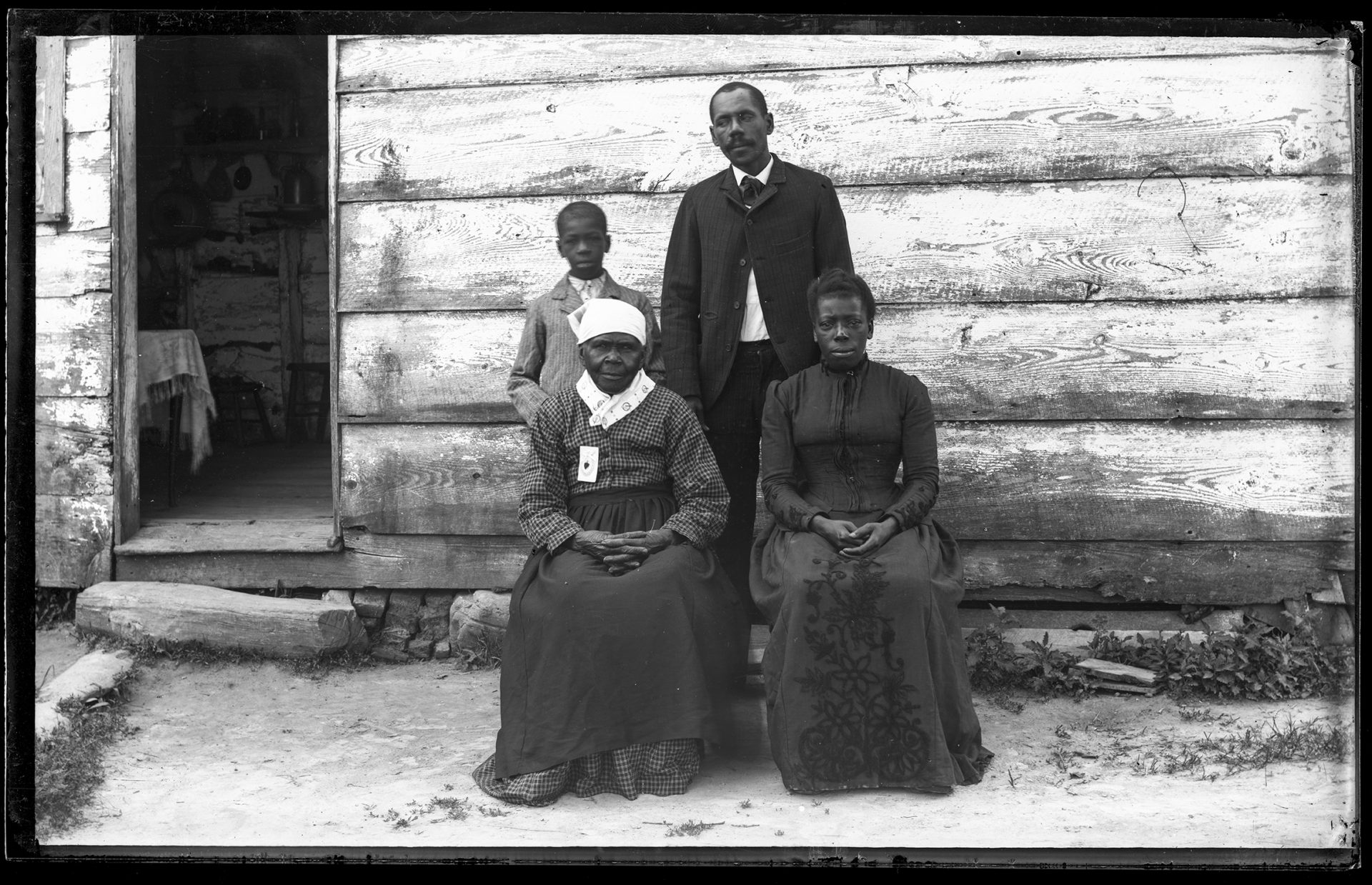

In 1838, the Maryland Jesuits sold over 314 enslaved people, now known as the GU272+, to save a nearly bankrupt Georgetown. The course’s creation grew out of calls from students and GU272+ descendants for Georgetown to reckon with its own history of enslavement, and teach it. These grassroots efforts culminated in 2015, when Georgetown established the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to “establish a dialogue on Georgetown’s historical ties to the institution of slavery.”

For Adam Rothman, a historian of American slavery, the class is a “vindication” of the group’s efforts and accompanying initiatives, including Georgetown’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Its Legacies, where Rothman serves as director.

“It feels amazing. I can’t really describe the feeling I had this past Tuesday,” Rothman said days after the course’s first meeting. “To see the ICC Auditorium filled with first-year students ready to have the kinds of conversations that we’re having in this class, to see the excitement and the energy in the room, was really incredible.”

In the class, students receive a weekly lecture from Rothman on topics ranging from slavery’s role in Georgetown’s history to the meaning of one of the university’s Jesuit values: “faith that does justice.” Along with these lectures, students participate in discussion sections where professors facilitate small-group conversations.

“This is a collective enterprise, and it’s really important for the university to have this class as part of its curriculum, because it will help new undergraduates at Georgetown understand where they are,” Rothman said.

The class tackles a few grounding questions over the course of the semester.

“What is this place? What is this university? What is its history? What makes it special? How do we solve problems together?” Rothman said. “It’s a culmination of the effort to really get our university community to learn the history and to work through its implications for today.”

Students come up with a question after lecture to pose during their section to spark conversation over confusing or difficult topics covered, from Georgetown’s role as a “global university” to the university’s decision not to add a $27.20 charge to students’ tuition to fund reparations for the GU272+. From there, conversations develop with occasional insight from facilitating professors, who belong to myriad academic disciplines.

“I study African politics, and with the history of politics in Africa, race, power, and justice are central to what I teach about,” Lahra Smith, who teaches in the African Studies program and leads a discussion section, said. “In that sense, it’s not something new to what I’m doing, even though the class itself is new. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for many years personally, but also intellectually and as a teacher.”

Smith’s section highlights another element of the course: students studying at Georgetown’s satellite campus in Doha, Qatar, also participate in the class. While 12 of Smith’s students attend discussion in person, the other 12 attend via online conferencing.

“At Georgetown, we have students who come from all over the world. But when people are physically in another part of the world, it gives you that reminder to always be thinking that the American-centric perspective is not the only perspective on these histories,” Smith said.

According to Smith, these discussions benefit from a diversity of experiences just on account of where participants come from.

“People know about America’s history of slavery. When you bring that into the global context, and we talk about racial inequality in the United States versus in the Gulf states, that becomes an opportunity to broaden the way that we think about our own experience,” Smith said.

While the exact trajectory of the discussions depends on the section, some students who had previously been unfamiliar with these topics were surprised by what they learned. Stacy Liu (SOH ’28) is one such freshman, who said her first Race, Power, and Justice lecture about the GU 272+ helped her realize the importance of these conversations.

“When I was applying, on the website there was virtually no information,” Liu said. “So I think that it’s really important to talk about the systematic disparities, and also how you could address them as a student and even after you graduate.”

Homework assignments that supplement the class meetings can also be thought-provoking. For example, one reading assigned to students was a university document written by founder John Carroll that discussed his desire for Georgetown to feature religious and cultural diversity. When Autumn Rain Nachman (CAS ’28) compared this document to the university’s historic mistreatment of minorities she had been learning about, she uncovered a contradiction.

“It was really interesting, as I felt like they were trying to introduce us to the idea of, ‘This is something we’ve always wanted,’ even though it’s very evident that it’s not something that Georgetown has always practiced,” Nachman said.

Faculty and first-years alike have expressed a genuine interest in the class’s themes—as well as a desire to make change by platforming marginalized voices, such as GU272+ descendants and the university’s facilities and dining workers.

“The first thing that we can do is start working on issues on campus,” Nachman said. “Then of course, beyond Georgetown, the discussion of reparations and reflecting on history in a reflective and contemplative way is so important, especially because students want to work in D.C. or in things like lawmaking and business that shape the next 200 years for America and beyond.”

But working to achieve social justice, whether on campus or beyond, starts with understanding social issues. Race, Power, and Justice at Georgetown motivates students to do just that.

“It’s important for everybody to recognize where we came from, the mistakes that we’ve made,” Nachman said. “And how we move past that.”