Content warning: this article discusses systemic racial injustice and references the history of slavery in America.

The Georgetown Art Galleries unveiled two new exhibitions by internationally renowned American contemporary artist Kara Walker on Sept. 21. The shows, Kara Walker: Back of Hand and Kara Walker: Prince McVeigh and the Turner Blasphemies, are scheduled to be on view until Dec. 3.

The exhibitions, displayed in the de la Cruz Gallery at 3535 Prospect Street NW and the Spagnuolo Gallery at 1221 36th Street NW, respectively, are the first presentations of these works in Washington, D.C.

Known for her iconic cut-paper silhouettes, Walker employs her art to comment on the history of American slavery, political violence, and sexuality. She urges viewers to critically examine the tragic past of slavery while looking at the pervasive racial injustices, including police brutality and white supremacy, that remain prevalent today. With shows worldwide, she is often regarded as one of the most prominent contemporary American artists.

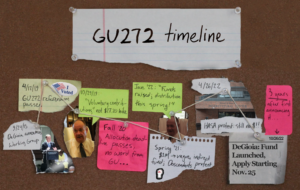

The new exhibitions reference Georgetown University’s long history of enslavement, including the sale of over 272 enslaved people in 1838—the GU 272+—to keep the university financially afloat. Walker’s works encourage students to reflect on this event which they benefit from, contextualizing it in a modern art conversation.

“[The exhibitions are] directly relevant to the GU272 and reimagining those histories through a contemporary art lens and how we look at the history of racism, representations of enslavement, and what’s happened on this campus,” Emma McMorran (M ’22), exhibitions and public programs manager of the Georgetown Galleries, said.

In her stop motion film Kara Walker: Prince McVeigh and the Turner Blasphemies, Walker shows the drastic impacts of white supremacy, influenced by the South’s legacy of slavery. She used paper silhouettes to recount the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing, a domestic terrorist attack that killed 168 people. She also chronicled the 1998 killing of James Byrd Jr., in which Byrd, a Black man, was violently murdered by white supremists.

Walker’s film, which uses these two historical examples, was created in response to the Jan. 6 insurrection in 2021, emphasizing extremist ideologies that have become widespread in the American public.

“[The film] recreates different historical representations of crimes that occurred against Black bodies and looks at them through an artistic lens,” McMorran said. “It explores the history of violence and the light and beauty of remembering the death of those people.”

The other exhibition on display, Kara Walker: Back of Hand, further explores this journey in an effort to present an accurate portrait of American history. Walker used watercolor, gouache, ink, and graphite, to create a series of drawings and murals. She drew on influences from the political works of Francisco Goya, a Spanish painter and printmaker, and the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages to tell the story of Black experiences that are often forgotten or mistold.

“Knowing something like the back of your hand, that saying, it’s like something that you love and is familiar, but that can also slap you and inspire violence,” McMorran said about the exhibition’s title and message.

Kara Walker: Back of Hand includes two mural sized pieces titled The Ballad of How We Got Here and Feast of Famine. These drawings signal a shift in the direction for Walker’s work. Text covers the paper and cutouts overlap to create the image, unlike anything the artist has produced before. These new creations provide an opportunity for visitors to engage with work that has never been researched or analyzed.

“Regardless of your background, [when you’re] around art, you can find it engaging, fun, playful, and political,” McMorran said. “There’s something, some meaning, that can come from any work.”