The word “Eden” makes me think of a heavenly paradise. When I visited Eden Center, a Vietnamese strip mall in Falls Church, Virginia, for the first time, it did not fall short of my imagination. The Eden Center, its parking lot constantly overflowing with cars, is designed like a maze; every corner pulls me to different shops, boutiques, and eateries. From a ready-to-go banh mi to a full banquet of noodle assortments, this plaza has it all for those who yearn to explore or revisit Vietnamese cuisine. When I walked into this hypnotic place for the first time, I couldn’t help but ponder over the question—how did Eden Center come into existence?

After my visit, as I began to unearth the past through further online research, I realized that the community behind Eden Center has had a complex history of displacements. After the Vietnam War drastically altered Saigon’s political landscape, Vietnamese Americans struggled to secure an enclave in the United States. This challenge was only heightened by gentrification. Recently, the communities in Eden have faced a similar threat: a plan by the Falls Church City Council to redevelop the area. With this context, it is more important than ever for Eden Center to remain true to its identity: Vietnamese, through and through.

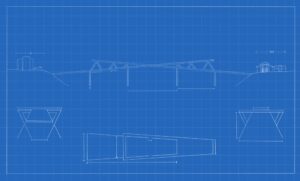

Eden Center is the largest Vietnamese commercial center on the East Coast. Currently, it is comprised of a plaza home to more than 120 family-owned restaurants, supermarkets, and shops. The strip mall is a major commercial center, generating a tax revenue of $1.3 million in 2020. However, the journey to becoming a successful Vietnamese strip mall was not—and still is not—smooth sailing.

During the two decades of the Vietnam War, multiple waves of Vietnamese refugees fled to the United States, fleeing the violence and hoping to establish roots in new soil. Many settled in the D.C. area, and in the early 1960s, a Vietnamese commercial enclave was established in the Clarendon neighborhood of Arlington. However, frequent visitors to this Vietnamese cultural hub did not have much time to cherish this place. Due to the construction of a D.C. Metro stop and the rising rents that came along with it in the late 1970s and early 1980s, many Vietnamese Americans were pushed out of the neighborhood.

Resilient against a myriad of past struggles, the community responded quickly to changing circumstances. Eden’s origins can be traced to the Plaza Seven Shopping Center, which was once nestled in Falls Church––where rents and building costs were more affordable compared to Clarendon. After the Grand Union supermarket located in this center moved out, a group of Vietnamese businesspeople who were originally displaced from Clarendon began renting vacant spaces inside.

As more Vietnamese Americans moved into the area, the name, “Eden,” was given to the emerging strip mall in honor of the beloved Eden Arcade market in Saigon, Vietnam. Dating back to the 1940s, the Eden Arcade was a cultural heritage site until its demolition in 2011.

My Saigon-born mother recalls how Eden Arcade, with its art collections, souvenirs, and food stalls, was a magical place to her as a young child. While she explained that “a typical day in Saigon was always hot and humid, walking into Eden felt like entering a different portal. It was always cool inside, even though there were no air conditioners.” In its own way, the Eden Center in Falls Church is like walking through a portal too—the selections of Viet cafės, nail salons, and banh mi stalls practically transport me to the streets of Saigon. Especially after the demolition of the Eden Arcade, there is the comfort in knowing that another Eden still exists, even in a realm that is oceans away from Vietnam.

Throughout my childhood, my parents sought out the best Vietnamese restaurants, cafes, and shops, but to no avail. The never-ending ache for the food of their motherland was a yearning that seemed impossible to fulfill while we lived in Australia, thousands of miles away from it. You can take my family out of Vietnam, but you cannot take Vietnam out of my family.

When I told my grandmother that I was going to study abroad in Washington, D.C., she insisted, “You have to go to Eden,” and presented me with a photo of a vibrant red, pagoda-style archway, with the sign, “Eden Center” attached to it. In 2025, after arriving in D.C., my parents helped me settle in for my semester abroad. They were instantly struck by the yearning for the familiarity of Vietnamese culture once again. Recalling my grandmother’s recommendation, we rushed to Eden Center.

My parents immediately immersed themselves in this place, using their first language to order and converse with people who understood them via common hand gestures and spontaneous code-switching. From devouring steaming hot phos to fresh pâté chauds, Eden Center was a blissful paradise for us. This is why Eden Center is an important cultural anchor for Vietnamese Americans: it is a safe space that creates a sense of belonging between people with the same cultural background. Especially given Vietnamese immigrants’ traumatic history of displacement from Clarendon and Vietnam, it becomes clear how crucial it is to protect this place.

In 2021, the East End Small Area Plan was proposed by the Falls Church City Council. This plan outlined investment strategies and redevelopment opportunities in small areas that are approximately 10 blocks in size—one of which includes the Eden Center. The redevelopment plans included improving structured parking lots and building new housing. Even though this plan purports to affect the Eden Center, initial meetings to develop the plan lacked representation from the local Vietnamese American community. By reflecting on Eden’s past and how Vietnamese businesses were once displaced from Clarendon, locals worried that history would repeat itself. Redevelopment of the area could result in higher rental prices, ultimately leading to the displacement of the community.

The final iteration of the East End Small Area Plan (2023) included notable changes thanks to local advocacy efforts. In particular, Viet Place Collective (VPC) emerged as a crucial voice for Eden Center. Mostly consisting of second and third-generation Vietnamese Americans, VPC works to communicate the concerns of Eden Center business owners and service workers to the City Council. Crucially, they requested additions be made to the East End Small Area Plan to protect against the risk of displacement. This included creating a plan to support existing tenants and protect “legacy businesses” and provide businesses with services, such as discounted legal assistance and access to a Vietnamese-speaking outreach specialist. To place further emphasis on Eden Center’s Vietnamese identity, the VPC also pushed to have a “Saigon Blvd” sign displayed near the strip mall to pay tribute to those who moved here after the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

Two years later, this wish was fulfilled. On January 22nd, 2025, an honorary Saigon Blvd sign was unveiled on the 6600 and 6700 blocks of Wilson Boulevard. This honorary designation is particularly important in 2025, serving as a symbol of the 50th anniversary of the fall.

I set foot in Eden Center at a pivotal time, on the verge of this important celebration. The Saigon Blvd sign had not yet been unveiled, but I could sense the community’s eager anticipation for the celebration and excitement at the possibility of future growth. Currently, there is a new Pop-Up District in Eden, which offers restaurant spaces with three-year leases, encouraging young Vietnamese entrepreneurs to start businesses without having to commit to a long-term lease.

Despite the push to establish new shops, I noticed that the older restaurants and bakeries remain the most popular spots in Eden Center. Places like Huong Viet, Mi Lacey Eden, and Saigon Bakery & Deli had extensively long queues of customers, regardless of the hour. Huong Viet was established in 1987 and is one of the hottest restaurants in Eden Center, perhaps because of its reputation for authenticity.

I believe that what drives the popularity of Eden Center is the desire to revisit fond memories and eat the food of one’s childhood. For Vietnamese Americans, connecting with these dishes bridges the gap between their family’s birthplace and their home in America. Rummaging through childhood food memories is a poignant way to reconnect with our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. Often, these remembrances are tied to family gatherings: we can recall the rifts and banter, the rubbing of shoulders, and the hands reaching out to the shared plate in the center of the dining table. Through its familiar food and community, Eden connects all generations to Vietnam, at the same time. From first-generation Vietnamese Americans who fled the war to third-generation immigrants who find comfort in being close to memories of their ancestors, Eden Center serves as an anchor for the local Vietnamese American community.

As a student who is studying abroad in a new country, oceans away from my loved ones, visiting Eden Center makes me feel closer to them. Surrounded by the language, cuisine, and music that I am familiar with, I am transported to my grandparents’ home back in Saigon. For me, this place is my anchor in a new, unfamiliar country. Because of this, places like Eden Center must continue to exist as a gathering space for the Vietnamese community. In order to protect our strip mall, the City Council needs to focus on protecting existing businesses that have been nurtured by generations of Vietnamese Americans. It is more important than ever to promise to the people of Eden Center that the businesses they built and roots they put down will continue to prosper and thrive.