Growing up, my sister and I were two peas in a pod. We did everything together and were almost inseparable. As Black people in a predominantly white town, she was the person I could go to for support. She understood me because we had similar experiences, like having to code-switch and feeling like the odd one out. As we got older, however, our paths split. My sister chose to go to Howard University, a historically Black university (HBCU), while I chose to go to Georgetown.

At the time, I was worried that we would be completely disconnected from each other. I thought that since she stopped trying to fit in and make white people comfortable, while I didn’t, we would no longer understand each other. I believed our diverging experiences of Blackness would make us unable to open up to each other. I was wrong.

“Personally, at school, I feel like I’m way more open about who I am as an individual than I was in high school,” Hadeia Liburd, my sister who is now a senior at Howard, said. “I act very different when I’m here at school, and the [way] people know me here at school is very different from how you know me, because of the perception I’m putting out.”

In our hometown, my sister was reserved. She didn’t talk much in class and others expected her to act this way. In high school, she once defended herself against a white guy who was bothering her, for which she got in trouble. Her teacher was “surprised” by how she acted. After that moment, she continued to be the quiet student. Last year, I had the opportunity to sit in on a couple of my sister’s classes at Howard. She was more vibrant and happy. She wasn’t scared to answer the questions that no one else knew the answer to and was comfortable expressing her thoughts.

My experience at Georgetown, a predominantly white institution (PWI), not only differs from my sister’s experience but is further challenged because of my size. Being a plus-size Black woman at Georgetown forces me to constantly deal with racist or fatphobic comments in an environment where very few people would understand what it’s like to deal with hateful and exclusionary experiences.

“If you’re at a PWI, you’re already the minority because you’re Black. So now you’re Black and gay, or you’re Black and plus-size, or you’re Black and you have a disability. Now you’re just in a smaller minority group than you already were,” Kaniyah Purcell, a senior at Howard University said. “And I feel like that can give you a sense of loneliness, or [make] you feel like you’re always out of place because you can’t find your circle, versus at an HBCU, we’re all Black, so you’re not in that minority circle anymore.”

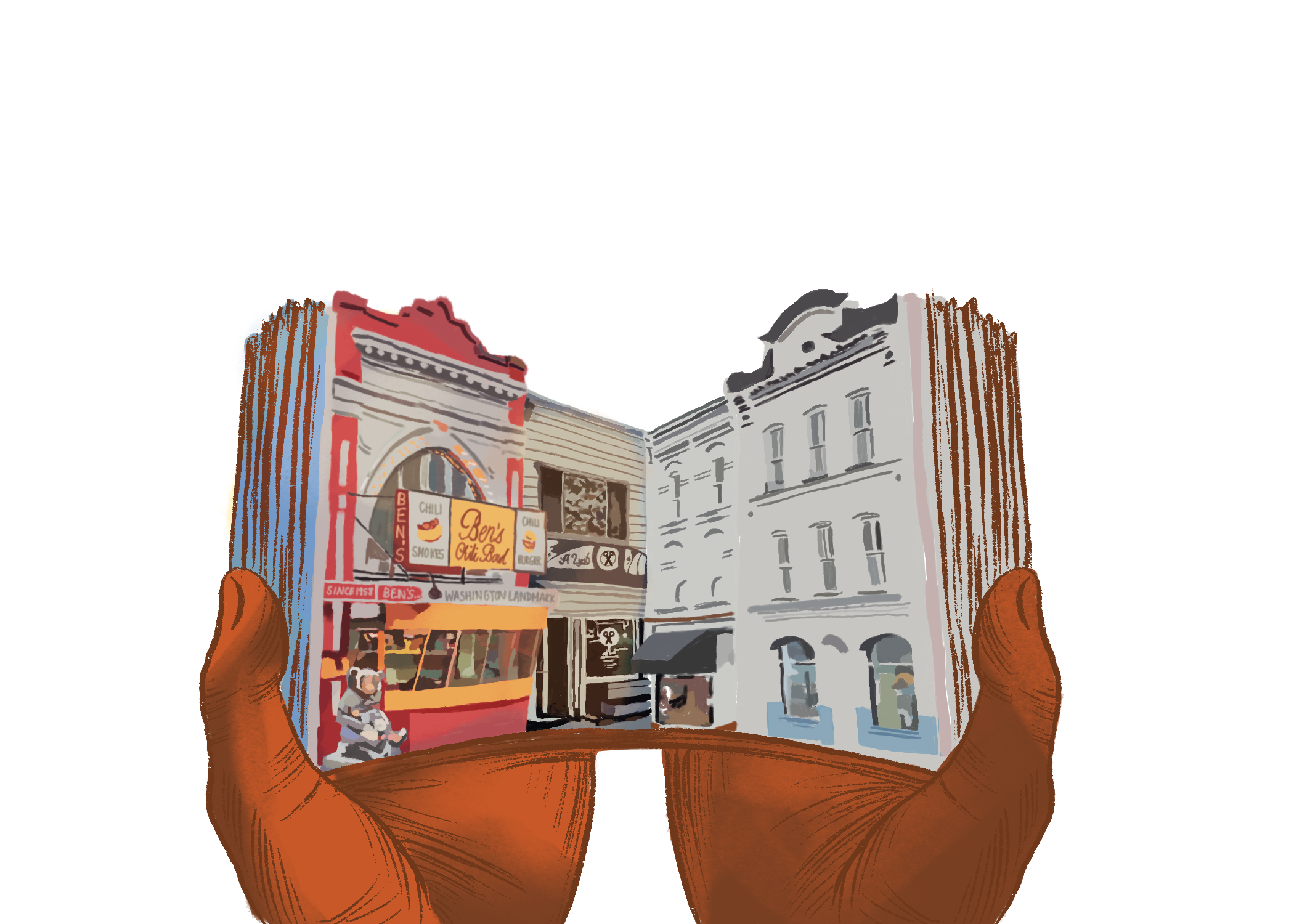

I could tell my sister felt comfortable at Howard, but what she really fell in love with was the city. It was a place where finding spaces catered to her Afro-Caribbean heritage was no longer as great of a struggle. Caribbean restaurants were less than a ten-minute walk from Howard’s campus, and Black hair salons were easy to find. At Georgetown, my experience has been the complete opposite: the neighborhood is filled with places that cater primarily to its wealthy and white community members, from the cuisine to the salons. All of this has made me feel out of place.

“I feel like not having those things accessible to Black Georgetown students would continue the othering that could be happening there, they aren’t able to get any sense of community or culture where they’re from, because there’s nowhere around for them to experience that,” Hadeia said.

Some Black Howard students enter college never knowing what it’s like to be surrounded by Black people and Black culture all the time. My sister and I were lucky enough to have been part of the Boys & Girls Club in our hometown, where we could engage with our culture and people who looked like us. Students who didn’t have this have since found their experience at Howard to be very affirming.

“My experience has been very eye-opening. In high school I went to a majority white place. I never really had as many Black people around me as I do now. And it’s been very validating for myself, being more comfortable being Black,” Kaylee McKinney, a senior at Howard University, said.

“This place, this area, is where you’re going to find very intelligent Black people in one spot, especially with creativity,” Justin Gholston, a Howard senior, added.

At Georgetown, only two of my professors have been Black, and, being a Government and Psychology double-major, I don’t expect this number to increase. Georgetown’s percentage of Black faculty members is only about 20% compared to Howard’s 85%. Having Black professors created some of the best experiences for me on campus. I was able to relax and take a break from trying to fit in. I didn’t have to worry about being too loud or confrontational out of concern for how my professors would perceive me.

“I would constantly be tired between being what white people think Black is, and being what an actual Black person is,” Purcell said. “I feel like here at Howard, the faculty is Black, or they are minorities, versus going to a PWI where most of the faculty in engineering will probably be white men. Now it’s like, how do I build a connection with you? How do I explain to you what I’m going through and have you understand it?”

I recognize that being a student at Georgetown has given me some privileges. Howard students have to deal with other people’s false and negative associations with their university, which is not an issue for me with Georgetown. However, it was my ignorant assumption that Howard students would want their college experience to be different. I thought that everything negative my sister experienced meant that she regretted her choice.

I have never taken the time to understand and listen to my sister or other Howard students about their experiences until now. This is where I believe the disconnect between my sister and I comes from, reflecting a larger one between Georgetown and Howard students.

“I know plenty of Black Georgetown students, but I feel like there’s a huge disconnect between the white students [at Georgetown] and Black students at Howard because they don’t put in the effort to come to Howard and get to know us. There are plenty of times when Howard students are on Georgetown’s campus, but I feel like I never see Georgetown students on Howard’s campus unless they’re going to U Street, and then it’s like, you’re just passing through, you’re not stopping to see what we’re about,” Purcell said.

On campus, I don’t often hear Howard discussed by people relative to other D.C. universities, but when it is, some comments made are hard to forget. I have overheard people saying they are scared to go to Howard’s campus because of crime. These comments only further push the idea that people should be scared of Black communities.

Despite this perception, crime is as much of a problem on Georgetown’s campus. Nearly every week in February this year, there was a crime reported on Georgetown’s campus, mostly involving theft.

“I would say Georgetown students feeling like they can’t come on Howard’s campus for crime is a cop out, because living in D.C., there’s crime everywhere. You could get robbed in Dupont, you can get robbed at the Washington monuments,” Purcell said.

In addition to being perceived as a more dangerous campus by some, President Trump’s executive order to cut diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs has made some Howard students worry about their future after graduating.

“It definitely causes a lot of us to feel unsafe and wonder if we’re going to be a target because we attend Howard University and because we attend a HBCU, whether we’re going to be targeted to not work for a company or be denied from our grad schools because of our Blackness,” McKinney said.

Though I have worried about how the DEI cuts would affect me in the future, as a Georgetown student, it has never been a concern that my university would be viewed negatively because of the racial makeup of the campus. Seeing my sister stress about this has caused anxiety for me and our family overall.

With companies continuing to rollback their DEI initiatives, Howard students believe that it may be time to start investing in our own community rather than supporting companies that bend to political pressure.

“I don’t think they deserve my dollar. And I think we are starting to see the ramifications of this, because there’s a lot of Black people that are starting to be more confined and are starting to spread their money into more Black-owned businesses and more businesses that actually care about them,” Gholston said.

This city is divided, and while some students don’t have to deal with these negative perceptions, others don’t have that luxury.

“I feel like white people try to just shield themselves from not seeing what’s going on with Black people or minorities,” McKinney said. “But then it’s like, how can you say that you want to build those connections, or you want to have Black friends and do Black things, but you don’t want to have Black people problems. I never understood that.”

However, moving forward as one may be something that is easier said than done.

“I think it’s important for us to be on a basic level understanding that we are all humans who deserve respect and deserve the same rights as the next individual. And until that happens, I don’t really see us moving all the way forward or really coming to a place where it’s true unity. I feel like it would take some time. It would take some dismantling of a lot of systems, and also not putting people on pedestals that perpetuate and say harmful rhetoric,” Hadeia said.

Talking with Howard students opened my eyes to the experiences and issues of young people that one doesn’t hear about at Georgetown. These student voices don’t tend to be uplifted by other communities, but it’s time that we start paying attention to their needs and allow them to speak for themselves and their own experiences.

After talking to my sister and hearing her concerns, I realized that a lot of the issues she had were because she was Black in the U.S. I initially worried that our experiences would be too different; however, sharing the same background has made it clear that my sister and I will forever be connected. Regardless of the universities we graduate from, our bond will never be broken. Although I may not ever fully understand what she has to go through, I will always be there to listen.

Imani’s note: This piece was informed by interviews with Hadeia Liburd, Kaniyah Purcell, Justin Gholston, Kaylee McKinney, and Gideon Boadu. A special thank you to my sister, I love you.