Twenty-six years ago, Fernanda Montenegro returned to Brazil to the sound of ringing applause. She had just made history at the 1999 Academy Awards as the first Latin American woman nominated for Best Actress for her performance in “Central do Brasil.”

Montenegro—the “Queen” of Brazilian theatre and cinema—was a source of hope for the Brazilian people, who saw her as their chance to secure the country’s first-ever Oscar win. People gathered in bars, restaurants, and movie theaters to cheer her on, creating an atmosphere reminiscent of a “World Cup final.” Yet, she was up against household names such as Cate Blanchett and Meryl Streep and knew her chances were slim. Ultimately, Gwyneth Paltrow took home the coveted award in what has been deemed Brazil’s “most painful defeat.” Still, when Montenegro landed back home, a crowd gathered at the airport to applaud her for the recognition she brought to Brazilian cinema.

“We did the best we could,” Montenegro said in an interview upon her return. While she didn’t take home the Oscar, “Central do Brasil” won Brazil’s first Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Non-English Language, bringing international recognition to the country’s cinema industry. Montenegro had also been nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Picture, but lost to Meryl Streep.

Since then, no other Brazilian actor had received a nomination in that category.

That is, until this year when Montenegro’s daughter, Fernanda Torres, secured one for her role in I’m Still Here. Torres defied predictions and beat Angelina Jolie, Kate Winslet, Nicole Kidman, Pamela Anderson, and Tilda Swinton for Best Actress, reaching a milestone her mother had missed over two decades earlier.

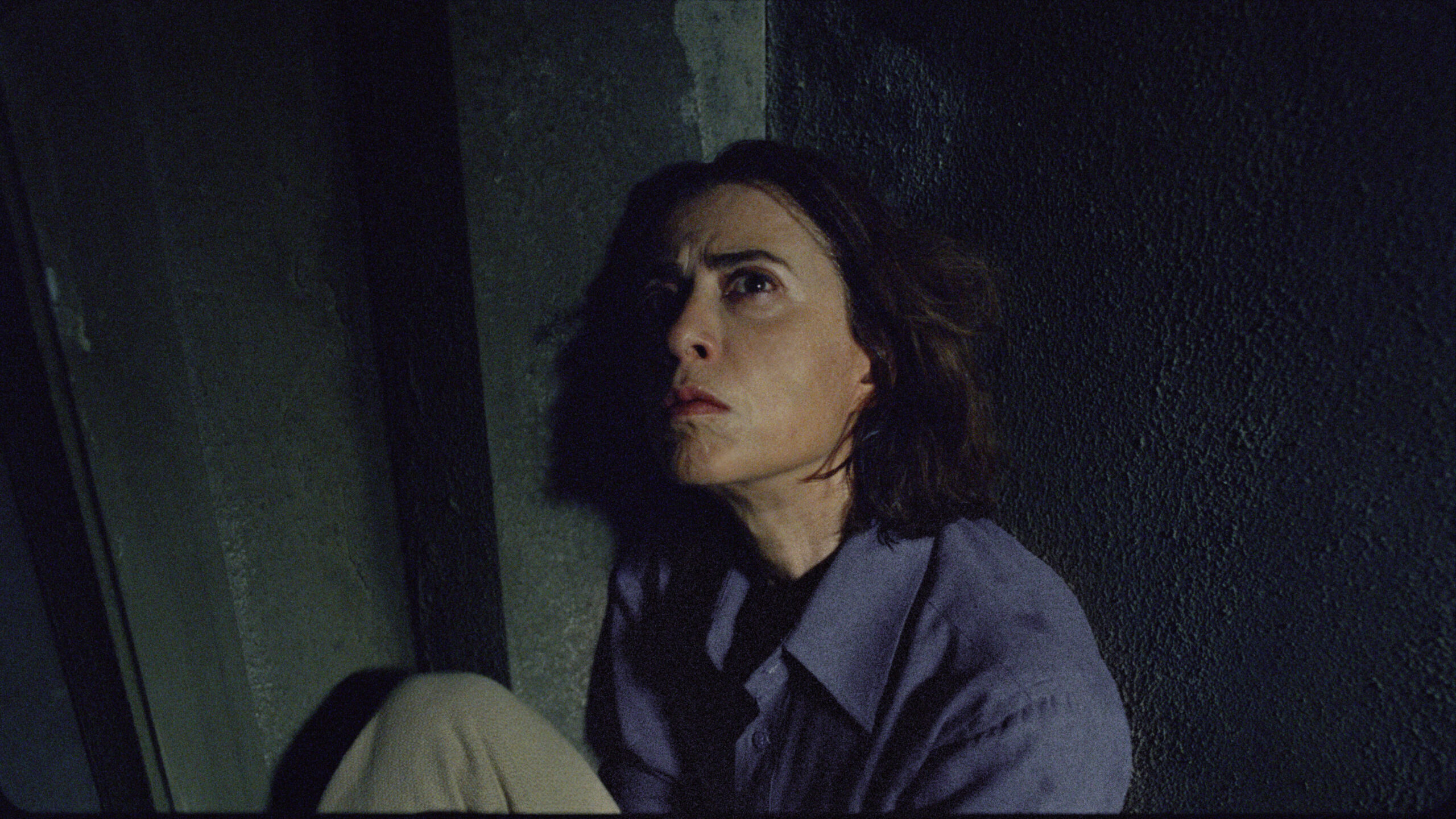

I’m Still Here, based on Marcelo Rubens Paiva’s memoir, portrays the devastating impact of Brazil’s military dictatorship (which lasted from 1964 until 1985), during which the government used torture, kidnapping, and murder to control the public. The film is deeply tied to the country’s political and cultural history, shedding light on a dark chapter that continues to have widespread ramifications on Brazilian society. The profoundly personal nature of the film made its Golden Globe win and three Oscar nominations—Best Actress, Best Motion Picture, Best International Feature Film—even more meaningful for Brazilian audiences.

It was also the first time a Brazilian film was nominated for Best Picture. When the awards ceremony unfolded, people around the country paused their Carnaval festivities to watch. One of Brazil’s largest broadcasters, Globo, even broke tradition by airing the Oscars instead of Rio de Janeiro’s iconic samba parades in most regions, emphasizing the national pride surrounding I’m Still Here.

Ultimately, Best Motion Picture went to Anora and Best Actress to Mikey Madison. The defeat was disappointing, especially for the latter award, as expectations had been high. Montenegro’s defeat in the same category in 1999 had been deemed ‘the biggest injustice in history’ by her fans and now history seemed to have repeated itself. Following the results, Brazilian fans flooded social media with posts and comments sharing their disbelief and calling for justice for Torres.

However, this year’s Oscar season also saw I’m Still Here nominated for Best International Feature Film, a category Brazil had never won despite four previous nominations. Fortunately, the film triumphed, securing the country’s first-ever Oscar.

In his acceptance speech, director Walter Salles dedicated the award to “a woman who, after a loss suffered during an authoritarian regime, decided not to bend. And to resist. So, this prize goes to her.” His speech refers to Eunice Paiva, the protagonist of I’m Still Here. Paiva is a mother of five who, after losing her husband to the military dictatorship in power, pursued a law degree and took it upon herself to fight for justice for the families of those who “disappeared” under the regime. I’m Still Here shows the devastating process of Paiva’s family being broken apart by her husband’s kidnapping, and her attempts to keep up some semblance of normalcy to protect her children. Throughout the film, Paiva gradually comes to terms with the fact that the government killed her husband and that her country will never be the same.

Celebrations over this win have been ongoing. During Carnaval, an announcement of the victory caused the streets to erupt in joy. People held Oscar statuettes and dressed as Fernanda Torres in street parades. Rio de Janeiro’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, announced plans to buy the house where the film was shot and turn it into a cinema museum. Brazil’s vice president and ministers expressed their pride in the film’s nominations, and President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva also weighed in, praising the film for showing the importance of resisting authoritarianism. He went on to say that this is a moment to feel “pride for our cinema, for our artists and, primarily, pride for our democracy.”

Beyond bringing international recognition to Brazilian cinema, I’m Still Here provides a platform for confronting the country’s violent past—something that has historically been overlooked. In 1979, the dictatorship passed an Amnesty Law that protected perpetrators of dictatorship-era crimes from prosecution, despite their extensive human rights violations. Fortunately, thanks to the visibility brought by I’m Still Here, this law is now being questioned. Last month, notaries in Brazil corrected hundreds of death certificates for victims of the dictatorship, finally acknowledging that their deaths were not natural, but caused by the state. This marks a significant step taken in the pursuit of justice, showing the real-world repercussions of I’m Still Here. The film’s exploration of authoritarianism and instability is particularly relevant in today’s context, as Brazil continues to grapple with the repercussions of a failed coup attempt two years ago in which protesters sought to instigate another military uprising.

Overall, I’m Still Here has become a defining piece of Brazilian culture, winning the country’s first long-awaited Oscar and igniting a much-needed conversation about Brazil’s political history. As Salles put it, “It’s not a film that has been recognized. It’s a culture that’s being recognized.”