What began as a dance workshop open to dancers of all skill levels has become Washington, D.C.’s first all-women dabke troupe—a cultural anchor for the five Arab American women who make up Malikat al Dabke.

Dabke is a folk dance that originated in the mountains of the Levant, encompassing Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, and Syria. The word dabke derives from the Arabic word dabaka, meaning “stamping of the feet.”

In dabke, dancers form a line, join hands, and stomp to a six-count rhythm, following a leader who keeps the pace. Each dancer relies on the two others beside them—chemistry, trust, and an instinctual awareness of the music and changing rhythm are crucial to the tradition.

Shared experience dancing with university teams drew the five women of Malikat al Dabka to each other, as they searched for a way to preserve traditions in spaces so far from home. The space they created, Sonia Abdulbaki said, organically evolved into a collaborative, professional dance troupe in Jan. 2023.

“We had choreographed dabke together in college and wanted to start a team,” Sonia said, speaking of her sister, Mae Abdulbaki. “It felt like a dream come true.”

Three years later, Malikat al Dabke now hosts dabke classes and workshops in D.C. and has performed across the United States, including at the Kennedy Center, the New York Arab Festival, and several embassies. However, these opportunities did not come easily.

The women each balance a full-time job while managing the dance troupe. Mae freelances as a film critic while coordinating Malikat al Dabke’s events and managing finances. Sonia, a user experience designer, has taken those skills and acted as their social media manager and website developer.

The women say there are advantages to self-management.

“We have full autonomy over our decisions and can navigate the direction we take toward achieving our goals and creative vision as a group,” Mae said.

“We don’t do it full-time yet, but that would be a dream,” she continued. “We love dabke, we love each other, and I think that translates into our performances.”

Each member’s decade of experience and passion shines through when they perform, hand in hand and smiling brightly. Malikat al Dabke’s collaborative spirit is evident.

“We all take part in choreographing dances. We learn from each other’s strengths,” Sonia said.

The troupe blends traditional dabke styles—Lebanese shamaliyya, Palestinian mish’al, and Iraqi chobi—with each other. They also incorporate newer, more modern variations, representing the varied backgrounds of the troupe’s members.

Washington, D.C. is one of the U.S. cities with the largest Arab American population, according to the Arab American Institute. Despite the approximately 11,000 Arab American residents, there is a noticeable lack of dedicated cultural spaces beyond restaurants and a limited number of art venues.

By studying, teaching, and performing dabke, the troupe aims to honor Lebanese heritage in D.C., reimagining and preserving centuries of history.

“When a lot of people think of dabke, they think of the very basic shamaliyya dabke,” Mae said. “But when you break it down, there are so many variations of dabke to learn, and that’s what makes it fun. The creativity doesn’t stop.”

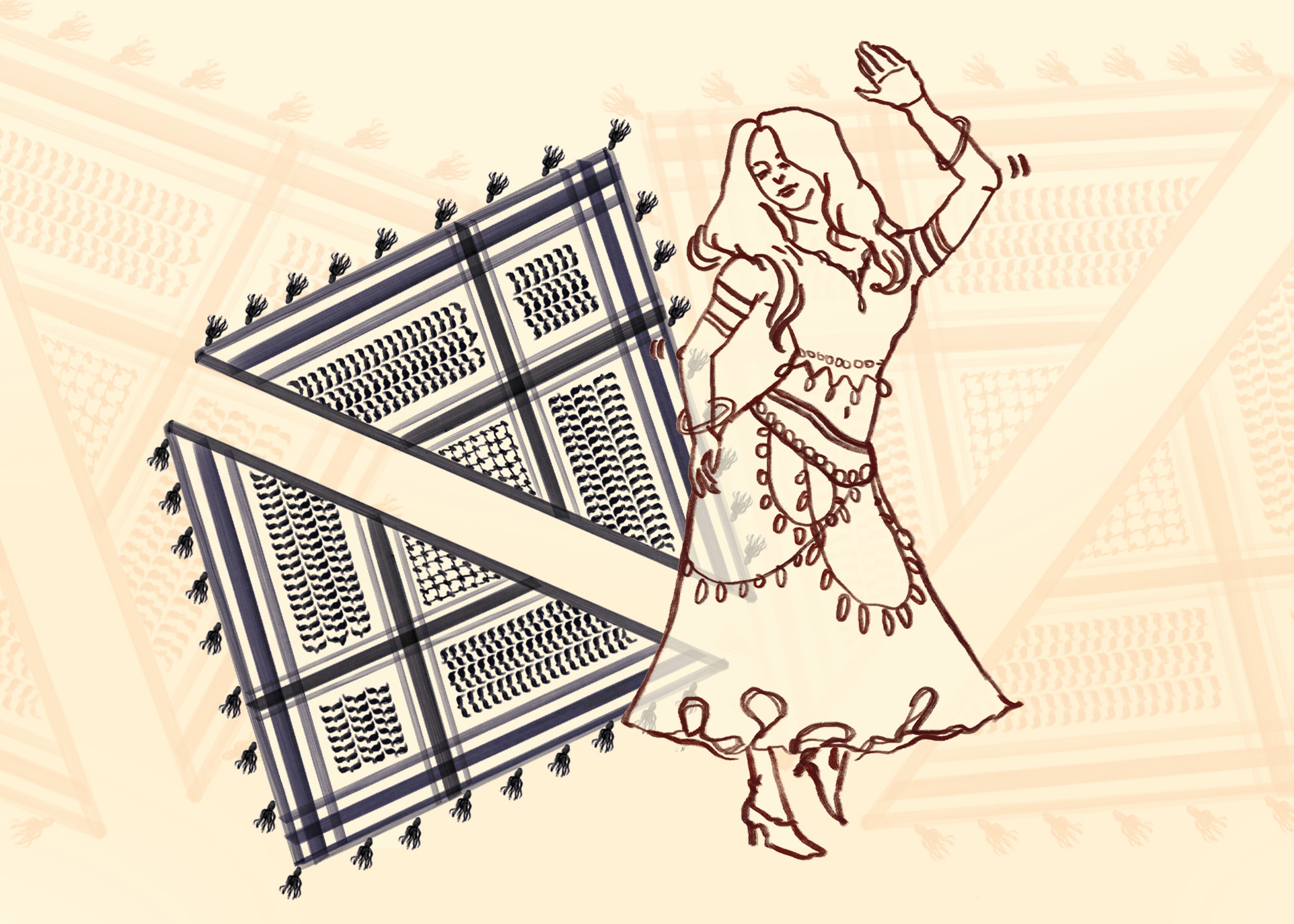

The varying dabke styles are reflected in the troupe’s costumes. The women don traditional Palestinian tatreez robes, open diamond-patterned vests purchased from Jordan, and shimmery green Lebanese-style gowns, as well as their black leather boots, the foundation of every costume.

“I have a dream of sketching out designs we really want and finding a designer who can make them,” Mae said. Sourcing traditional costumes in the U.S. is difficult, often resulting in garments that are too thick and stiff to comfortably dance in.

While the women stay connected to their roots through dabke, the context of where they are living and performing is not lost on them. Often, the troupe has to navigate performing in front of crowds who have never seen dabke live before, and who sometimes lack an understanding of women’s historical role in the tradition. Dabke is often portrayed as a male-dominated art form—but in Lebanon and across the region, both men and women have historically danced dabke.

“There’s always the random person who will ask a very sexist question,” Mae said. “But usually non-Arab communities are very enthusiastic and want to learn more. They are intrigued by dabke’s origin stories and the dance itself because they have never seen it before.”

When asked if women belong in dabke, Mae answered: “Women have always done dabke. We have always been part of tradition.”

It was a woman, Mae’s own mother, who taught her dabke when she was only six years old.

“She turned on some Arabic music, grabbed my hand, and started dancing,” Mae said. “It’s my first memory of dabke and the music in particular is what has kept me so connected to Lebanon.”

Performing as Arab American women existing between two worlds is also central to Malikat al Dabke’s identity.

“I want Lebanon to keep publicizing our roots and fighting against colonization and the dissipation of our national identity and heritage,” Sonia said. “Dabke is a tradition that’s deeply related to unity. It is a communal dance in every aspect—its history, its circular formations, the holding of hands.”

Aspiring to perform in the Middle East, Malikat al Dabke will continue to perform and teach dabke in the U.S., working tirelessly to preserve Lebanon’s customs abroad.

“Lebanon has been through a lot and its people have been through a lot,” Sonia said. “It’s important for Lebanese everywhere to continue resisting and being who they are while keeping our culture and dabke alive.”