Rather than just accept the fact that steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs were part of the sport’s culture at the time, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, the electoral body for the Baseball Hall of Fame, has engaged in their own reprisal of the Salem Witch Trials. Any accusation against a player, no matter how scarce the evidence is supporting that claim, or even just simply playing during the Steroid era of the 1990s and early 2000s can be enough to squander one’s chance of earning the ultimate acclaim for one’s career.

As a result of this ill-advised witch hunt, some of the sport’s all-time greats, such as Barry Bonds, the all-time home run king, and Roger Clemens, the pitcher with the most Cy Young Awards ever, have found themselves without a Cooperstown membership card, because of their past association with steroids. Although it seems odd to exclude these two distinguished players from the Hall of Fame outright, it never really troubled me. Even before news of their past associations with performance enhancing drugs came to light, I never particularly cared for either athlete. Unlike some people, I never saw them as my role models.

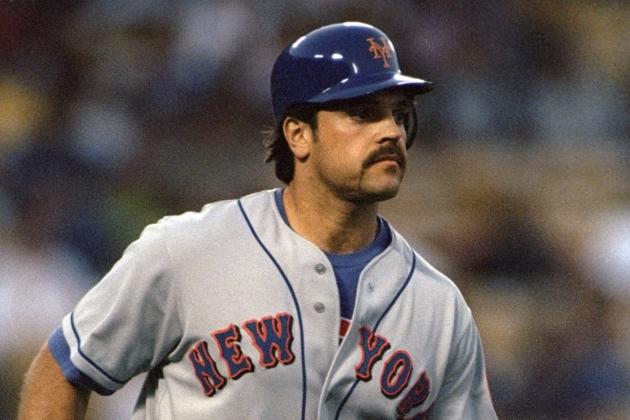

But my ambivalence towards the Hall of Fame selection process all changed this past week because it finally hit me personally. My childhood idol, Mike Piazza, the star player of my beloved New York Mets and the greatest hitting catcher in baseball history, found himself left out of the Hall of Fame in his third consecutive year of eligibility. To say that I was infuriated would be a tremendous understatement.

Here’s another tremendous understatement: Mike Piazza was my hero growing up as a kid. And unlike most childhood role models who end up disappointing their admirers, Piazza never did. He was everything that a young, aspiring Little Leaguer could ask. His sheer dominance in the batter’s box with his moonshot home runs, and his ability to get the clutch hit in dire situations made him an opposing pitcher’s worst nightmare. Combine that athletic ability with his mantra for doing things the right way—running hard down the first baseline and always making extra time for the fans for autographs and pictures—and you can see the reasons to why I adored him so much. I dressed up as him for Halloween three years in a row.

But childhood bias aside, Piazza was a damn good baseball player. A 12-time All-Star and 10-time Silver Slugger Award winner, Piazza has hit more home runs than any other catcher in baseball history. Not solely just a power hitter, Piazza is one of only nine players to hit 400-plus home runs, have a career .300 batting average, and never strike out more than 100 times in a season. If that’s not enough to convince you of his worthiness, consider how Piazza almost single-handedly carried an otherwise mediocre Mets lineup for over a half-decade, helping them reach the 2000 World Series. His arrival to New York via trade in the summer of 1998 helped rejuvenate a franchise that had been mired in the National League cellar for almost a decade. On a more sentimental note, he also hit the most significant home run in New York baseball history with his game-winner in the first baseball game played in New York post-9/11. For most baseball fans, these accomplishments would make Piazza a sure-fire hall of famer. But Piazza still finds himself without a plaque in upstate New York.

What was Piazza guilty of, one might ask? What did he do that has prevented him from joining the all-time greats in Cooperstown? The answer is simple: to the writers who fill out their Hall of Fame ballots every year, unless they can prove with certainty that a player of that era did not use steroids, it is not worth electing them. Like many accomplished players of the time, Piazza, as a result, finds himself punished for the crime of simply playing during an era tainted by rampant steroid use.

But this logic is flawed. Piazza, unlike some of the other players on the ballot this year, never tested positive in a drug test, never was mentioned in any of the sports’ supposed fact-finding investigations—most notably the Mitchell Report. He never had to testify before Congress for past steroid use and never was indicted in a federal court for using performance-enhancers. But that doesn’t matter to these writers.

I used to walk to the plate for an at bat in Little League and conjure the Shea Stadium public address announcer broadcasting in my mind, “The catcher, number 31, Mike Piazza!” Like many of my other peers who find their favorite baseball players of yesteryear not getting the credit they deserve, I’m now left wondering what it will take for the Hall of Fame to call my favorite athlete’s name.

Photo: Aubrey Washington/Getty Images