Illustration: Christina Libre

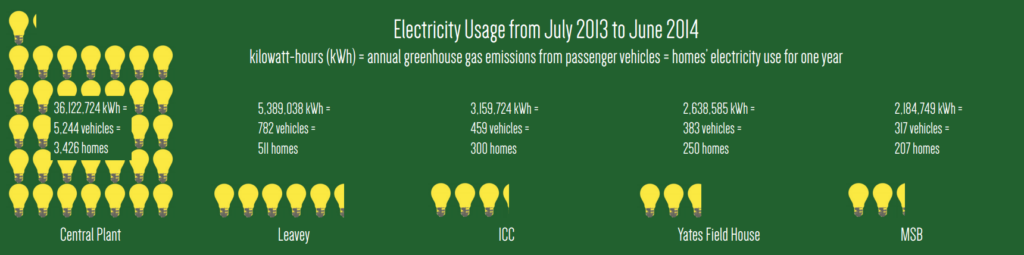

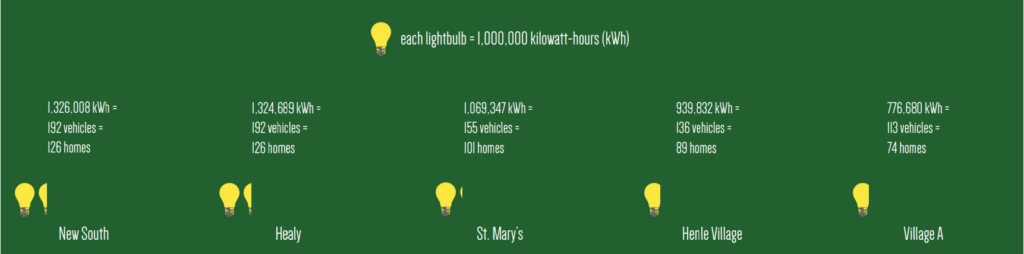

In September 1984, Georgetown turned on the photovoltaic array atop the Bunn Intercultural Center. Composed of 4,464 solar panels divided into 10 subarrays spanning almost 36,000 square feet, the ICC array was larger than any other rooftop solar panel array at the time of its construction. In their prime, the ICC solar panels could produce 300 kilowatts and 360,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity per year—an amount equal to the energy produced by burning almost 28,000 gallons of gasoline, according to the website of the Environmental Protection Agency.

The array, however, gradually deteriorated over the next 25 years. Grime from air pollution baked onto the panels, reducing their efficiency. From July 2009 to June 2010, the panels produced 164,300 kilowatt-hours, offsetting 13,000 gallons of gas. The panels exceeded their expected lifespan of 20 years, but by the time the array was shut down in December 2011, they were generating less than half of the energy they had produced during their early years.

While Georgetown works to fix and improve its renewable energy projects on campus, one student group has grown to question the university’s global environmental impact. On March 18 of this year three students from GU Fossil Free walked onto the stage in Gaston Hall while World Bank President Jim Yong Kim spoke about climate change. The students held a sign reading “Corporate leaders should not wait to act until market signals are right and national investment policies are in place. Georgetown divest now.” They were quickly escorted off the stage by officers of the Georgetown University Police Department.

Less than two weeks later, some of those same students and many of their peers met in the Leavey Program Room to discuss the university’s campus sustainability plan. The Office of Sustainability has led the drafting process since 2013 while receiving input from constituent groups including students, administrators, and university vendors and providers of energy. The plan, though still being drafted, will impact the day-to-day operations of the university’s facilities as they relate to the sustainability of Georgetown’s campus.

As energy concerns continue to generate dialogue on campus, environmental groups raise questions about how Georgetown uses energy sustainably and efficiently, and how its decisions impact global climate change. With numerous construction projects currently underway and several renovations in the planning stages, Georgetown stands at a pivotal juncture in its commitment to use resources sustainably.

Pledging to reduce Georgetown’s carbon footprint, President John DeGioia committed to cutting university emissions of Scope 1 and Scope 2 greenhouse gases to half of the FY 2006 baseline level by 2020. Scope 1 emissions are greenhouse gasses that Georgetown emits directly from sources it owns, while Scope 2 emissions are greenhouse gasses Georgetown indirectly emits by purchasing oil, gas, and electricity.

In Fiscal Year 2013, Georgetown emitted 87,881 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCDE) in total emission, including both Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. That year’s emissions saw a 19.4 percent reduction from Georgetown’s FY 2006 baseline, in which Georgetown emitted 108,981 MTCDE, equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of 15,000 homes.

According to Robin Morey, Vice President of Planning and Facilities Management, the university has already reached President DeGioia’s goal, cutting FY 2006-level emissions by 69.9 percent through the use of renewable energy certificates (RECs).

RECs are a tradable good that represent property rights to the environmental benefits of a renewable energy source. When a renewable energy generator produces 1,000 kilowatt-hours of energy for an electric grid, a REC is created. Other users of the grid can then purchase the REC from the generator’s owner. RECs reduce greenhouse gas emissions because they provide funding for owners of renewable power sources to create electricity for the grid that might otherwise have been created through greenhouse gas-emitting technologies.

“RECs create a market where people will bring green, sustainable power to the grid,” Morey said. “So that’s effectively how we’ve achieved [the 2020 goal], in addition to the other energy savings measures and efficiency gains.”

Georgetown owned no RECs in FY 2006, but by FY 2013, its purchases of RECs equalled 54,804 MTCDE in emissions. Purchasing RECs meant that the university’s 87,881 MTCDE FY 2013 emissions created just 33,077 MTCDE in net emissions. That year, the EPA recognized Georgetown as a Green Power Partner because it purchased RECs that totaled over 100 percent of its energy use in renewable power.

Purchasing RECs, though, does not mean Georgetown runs on renewable energy.

“Technically if you go on the EPA website, we’re [130] percent renewable energy power, which is wonderful,” Caroline James (COL ‘16), GUSA co-secretary for sustainability said. “But it’s slightly misleading, considering that it’s energy that we buy. Not that there is anything wrong with that. But right now, we’re not producing it on site, and it’d be better if we were.”

While RECs are one way the university has achieved President DeGioia’s goal of halving its carbon footprint, other updates to facilities across campus have improved overall energy efficiency.

According to Morey, the master planning process has prompted assessments of the condition and energy use of various campus buildings. The university has since implemented a variety of energy conservation measures to modernize these facilities. Upgrading a boiler fan and repairing steam traps in the central heating and cooling plant last year helped cut an annual 2,502 MTCDE—the equivalent of 528 cars off of the road—according to the Office of Sustainability’s website.

Georgetown’s commitment to LEED Silver certification for all new construction and renovation projects is another aspect of the master plan affecting energy use. LEED, or Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, is a program run by the U.S. Green Building Council to recognize buildings whose designs excel in efficient energy use and environmental impact. Through a point system, a building can receive different certifications based on its overall sustainability.

The Office of Sustainability hopes to receive LEED Gold certification for the Northeast Triangle Residence Hall, Former Jesuit Residence, and John R. Thompson Jr. Intercollegiate Athletic Center—all of which are currently under construction

“Technically, we use the word ‘committed’ to achieving LEED Silver, striving for LEED Gold, which is great,” Mandy Lee (SFS ’17), GUSA co-secretary for sustainability said. “At the same time, being in a city, from what I understand, LEED certification is actually a little bit easier because we’re already in a place where there’s public transportation access and a lot of other things that give us a little boost in the process. So I’d love to see the university take it a step further and really go for a loftier goal for all future construction and renovation.”

For almost 30 years, the ICC solar panels sat alone as a symbol of renewable energy on campus. Two years after they shut down, a new symbol emerged.

In 2011, Georgetown Energy (GE), a project-based student organization focused on promoting renewable energy both locally and globally, submitted a proposal for a new solar panel project on campus. Reforms to the Student Activity Fee Endowment led to GE’s receiving $250,000 to fund construction of “Solar Street,” a collection of solar arrays on the roofs of six townhouses right outside the front gates.

“Solar Street” produces 20,000 kilowatt-hours annually, 27 percent of the electricity needed to power their houses. It was the first instance of collaboration between students and staff members on a renewable energy project.

The project ultimately cost $40,000 because the townhouses could not support larger arrays. The remaining $210,000 have been used to create the Green Revolving Loan Fund, part of the Georgetown’s Student Innovation and Public Service (SIPS) endowment which helps finance students’ sustainability projects.

Currently, GE is working on a project to build another solar array, larger than Solar Street, on the roof of the Leo O’Donovan dining hall. Despite receiving preliminary approval, GE has hit roadblocks while trying to advance the project, according to Danny Watson (SFS ’16), a GE board member.

[pullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”green” class=”” size=”h4″]“Solar panels are sexy, but not a lot of students are realizing that we’re wasting just as much energy with halogen lights and lights that stay on,” he said. “Why are all these lights on right now? They don’t need to be on.”[/pullquote]

GE and the university have been working for over a year and half on the project, according to GE board member Meaghan Keefe (COL ’15). According to Keefe, Georgetown is currently in negotiations with an alumnus who has potentially pledged to fund the entire project. Keefe said that the alumnus hoped to earn back his or her investment through federal tax returns on renewable energy. Issues with the alumnus making revenue off the panels, even if only to break even on the investment, held the project up several months.

For the 280 to 300 panels to sit atop Leo’s, GE still needs to receive a formal structural assessment. Various building permits and approval from different neighborhood boards could also prolong the process. Georgetown and the alumnus continue to redraft their power purchase agreement, a contract that includes the sale of energy, so that the alum can own the array while the university uses the energy it produces.

“To some extent, the problem is there is no real institutional mechanism for students to be working with so many different offices in the university to try to push for a project,” Naman Trivedi (SFS ’16), a GE board member, said. “Everyone we talk to is supportive. No one is against it. The problem is these administrators also have full time jobs and, in most cases, it’s not within their mandate to engage students.”

GE has primarily worked with Audrey Stewart, director of the Office of Sustainability, on the Leo’s project. In an email to the Voice, Stewart wrote that she hopes that the project will generate a return over time to the student-run SIPS Green Fund. The details of this arrangement are still being negotiated.

Charlotte Cherry (SFS ’16), a GE board member, noted that although the Office of Sustainability has been supportive, its capabilities are limited. As a one-person office with student interns, much of GE’s ability to work with the office depends on its ability to accommodate them.

Danielle Huang (COL ’17), the treasurer of EcoAction and a student ambassador to the Office of Sustainability, expressed similar sentiments about the size of the office.

“We have a roundtable for social justice issues, but there should be a roundtable discussion for energy and for sustainability,” Huang said. “I think that if we could expand [the Office of Sustainability] into a department of sustainability and have more student interns, that would definitely help.”

Although its initial project area reached just beyond the front gates, GE has expanded its scope to include international renewable energy initiatives.

The group traveled to Haiti in 2013 and 2014, receiving funding through SIPS and Corp grants, to install revenue-generating solar-charging systems, which were sold to entrepreneurs who earned back the cost through the solar energy the systems produced.

“A lot of rural regions don’t have electricity access, so you need some off-grid solution to help them get electricity,” Trivedi said.

GE’s International Initiatives team hopes to begin a project in Paraguay at the end of the summer to provide a community that currently uses kerosene cookstoves with a biodigester, a system that takes in waste and produces methane for use as fuel and fertilizer.

While GE works directly to provide clean energy to a variety of communities around the world, GU Fossil Free (GUFF) continues its efforts on campus to convince the Georgetown administration to divest from international fossil fuel companies.

GUFF is part of a larger activist movement at peer universities which demands removing university endowment investment in fossil fuel companies. According to James, also a member of GUFF, 8 to 10 percent of Georgetown’s endowment is currently invested in such corporations.

[pullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”#088A29″ class=”” size=”h4″]“Why are we investing in fossil fuels when we’re trying to decrease their use on campus? It’s not a rational way to conduct business. If you were trying to stop smoking yourself, why on earth would you invest in tobacco?”[/pullquote]

Although the university has made great strides to reduce on-campus greenhouse gas emissions, its continued investment in fossil fuels conflicts with its goals, GUFF claims.

“It doesn’t make a lot of sense to me that we continue to invest in an industry that we’re actively trying to move away from on campus,” James said. “Why are we investing in fossil fuels when we’re trying to decrease their use on campus? It’s not a rational way to conduct business. If you were trying to stop smoking yourself, why on earth would you invest in tobacco?”

In January, the Committee on Investment and Social Responsibility rejected GUFF’s complete divestment proposal and instead recommended pursuing “targeted divestment from fossil fuel companies with the worst environmental records and most objectionable practices,” CISR Chair Jim Feinman said in a statement at the time of the decision.James sees partial divestment as an attempt by CISR to appease GUFF despite acknowledging the moral inconsistency of investment in fossil fuels.

Keeping with its continued efforts to lobby the university for divestment, GUFF has joined forces with other universities by supporting a multi-school divest fund. Alumni, students, and other members of the university communities can donate to the fossil free fund instead of their respective school’s endowment. Once a university divests, the organization will donate that school’s portion of the money invested in its fossil free fund to the now divested endowment.

“So Georgetown already has a pool of money that’s sitting there, being invested in a fossil free fund, that Georgetown can access whenever they decide to divest,” James said.

Georgetown’s Board of Directors will vote on GUFF’s proposal in June.

On March 30, James and Lee led the “What’s the Plan?” meeting of Georgetown Environmental Leaders (GEL), a coalition of environmental student groups. GEL members came to discuss a working draft of the campus sustainability plan and propose possible improvements. During a day-ending group discussion, students expressed a desire for their voices to be heard during the drafting process.

According to Morey, Stewart continues to meet regularly with student groups for their input on the sustainability plan.

Georgetown Fossil Free rallies for divestment on campus. File Photo: Ambika Ahuja/Georgetown Voice

Although the Office of Sustainability has sought student perspectives, the scope of campus sustainability may be too large for students to meaningfully impact the process, according to Cherry.

“There’s a lot of scattering of energy projects and sustainability projects in general,” Cherry said. “There’s a huge variety. … I don’t think that most students know about what’s happening … and so they can’t really have an educated say.”

But students and administrators both agree that simple measures like turning off lights, using air conditioning only when necessary, and unplugging chargers when not in use can greatly reduce campus energy consumption.

Watson hopes that building renovations and smarter uses of pre-existing energy sources can help Georgetown become more efficient.

“Solar panels are sexy, but not a lot of students are realizing that we’re wasting just as much energy with halogen lights and lights that stay on,” he said. “Why are all these lights on right now? They don’t need to be on.”

“Students are the ones who are using the lights and the energy, and yet most of the time they don’t have the ability to reach up to a light bulb and make sure that it’s an LED or CFL bulb. That’s just something that’s not really in student power,” James added.

Every fall, the Office of Sustainability facilitates a “Switch It Off” challenge between residence halls, encouraging students to conserve energy through a competition with prizes for the dorms that save the most energy.

Huang cites the Switch It Off challenge as an effective way to encourage students to examine their energy use. The freshman dorms, according to her, cut back the most on their energy use. “It’s all about the freshmen. When you get them interested in their freshman year, they’ll be more inclined to do these things more throughout their college career,” Huang said.

According to Morey, energy conservation efforts must be reconciled with campus safety.

“I can guarantee you that when you walk around campus at night, you’ll see lights on that don’t need to be on. But we need to [conserve] safely,” Morey said. “You know, recently, I got an Ideascale [suggestion], ‘Why do you have the lights on in Multisport Field late at night?’ Well, those are safety issues. It is a balance, but it’s one that we need to optimize to strike the right balance.”

Though making strides to increase its energy sustainability, Morey thinks Georgetown can and should continue to improve. Both he and Stewart emphasize that the university’s goals revolve around what they call the three Ps: people, prosperity, and planet.

“Our vision is really those three P’s … in support of GU’s core mission, thus advancing environmental sustainability, reducing operating expenses, and increasing the well-being of our campus community members,” Stewart wrote.

For Keefe, more student engagement on energy issues could not only improve Georgetown’s overall energy efficiency but also make the university a global leader in sustainable action and environmental awareness.

“I definitely think that Georgetown’s student body could have a greater awareness and sense of ownership of energy on campus,” she said. “I mean, we’re a great school and we’re leaders in everything else. I think it could be a real point of pride.”

Cover Photo: Christina Libre

[…] 2013, Georgetown had reduced its emissions by almost 20 percent from 2006 levels and lowered its environmental footprint by an […]