In a 2013 New York Times interview, writer Jeff Himmelmann observes Frank Ocean as he oversees the restoration and customization of one of his cars, a vintage 1990 BMW E30 sedan. The then twenty-five year old artist obsesses over minute details of the car, insisting that a mechanic change a piece of metalwork in the interior of the engine that would never be seen. “It doesn’t matter if you can see it,” Ocean says.

This sound bite perfectly encapsulates Ocean’s perfectionist mentality and his meticulous approach to his craft. And it might offer some insight to those who struggled to understand the endless delays and postponements of his new music.

On August 20th, Ocean finally released his long-awaited creation in a three-part project comprised of a visual album called Endless, a seventeen track album entitled Blonde, and a magazine of photos, poems, and personal essays, Boys Don’t Cry.

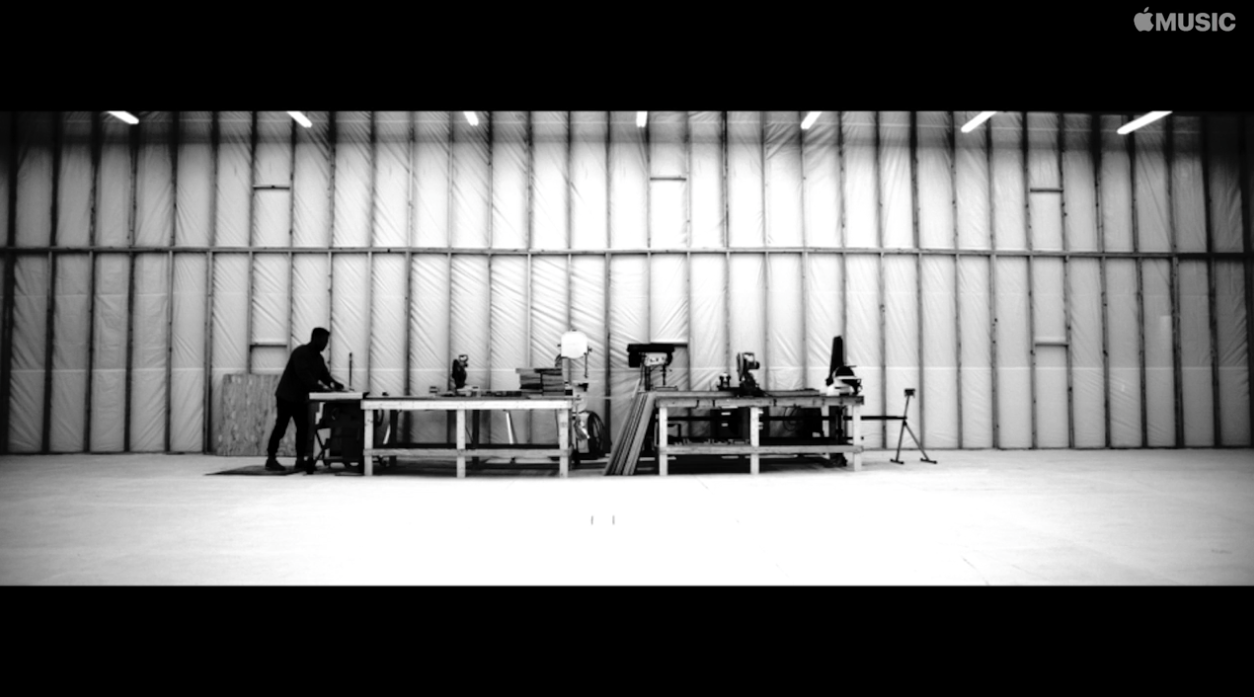

Endless is forty-five minutes of black and white footage showing Frank as he builds a spiral staircase, soundtracked by an eclectic yet hypnotic album. As Frank croons over atmospheric Rhodes and muted guitar, multiple Frank clones methodically cut wood, screw boards together, spray paint them, and arrange them in an ascending spiral staircase. A true work of minimalism, Endless symbolizes Ocean’s dedication to his craft and teaches important lessons about patience and deliberation. There is something beautifully simple and powerful about building something physical with your hands. The footage recalls that scene from Breaking Bad where Jesse describes his proudest accomplishment: building a box in wood shop. Frank’s painstaking carpentry mirrors his art in the way it demands time, care, and thoughtfulness–uncomplex things that we don’t always demand from our artists nowadays. I’m talking about artists like Taylor Swift, whose hits are mainly written by someone else, or Drake, who was accused of not writing his own verses, and whom Andre 3000 calls out in his standout verse on Blonde.

Apple Music

Like Endless, Blonde is in many ways an exercise in restraint. If Channel Orange was an impressionist masterpiece, Blonde is a postmodern sculpture, at times brilliant, at others inscrutable. Many fans wanted, nay, desperately needed accessible songs in the vein of “Thinking Bout You” or “Lost” from Channel Orange. Frank refused to appease them and instead pursued a singular vision, an aesthetic rather than a product. This artistic discipline is what separates Frank from many pop artists. Take Drake, for example. Views has smashed streaming records since its release, which is understandable. Full of club hits and easily digestible trap beats, it’s exactly what fans want and expect. And that’s not necessarily bad. But Views fails to push any creative boundaries or contribute any sociopolitical commentary; on the whole it takes very few risks, and as a result, fails to inspire.

Frank’s voice, which boasts ample range, a passionate, quavering vibrato and an arresting falsetto, is a treasure in and of itself, yet on Blonde it is often hidden or distorted, as on the opener “Nikes”. There are only a few brief moments where the talented vocalist really breaks loose; at other times he purposely sings dissonant, out of key notes. It is almost as if Frank feels his voice has already proven itself. The album also largely eschews hard-hitting beats and hooks; “Ivy” simmers but never explodes, “Self Control” features clean, quiet guitar, and several tracks are completely devoid of percussion. At the end of “Nights”, the only place where Frank indulges himself, he spits over a withdrawn trap beat for a paltry sixty-eight seconds. Blonde is often as austere as the white room in which he toiled, and the resulting uncluttered atmosphere allows for Ocean’s masterful storytelling to shine through.

Listening to Blonde, one might be tempted to compare Frank Ocean to Drake. Both are known to focus much of their writing on their love lives and personal challenges. Drake is touted as a sensitive lyricist, an infamous label that has been cemented by a multitude of memes. But the truth is, nobody can match Frank’s level of introspection, nor his poignant lyricism when it comes to love and relationships. “I’m not him, but I’ll mean something to you,” he sings on “Nikes,” astutely illustrating the torture of unrequited love. Drake isn’t a bad rapper, but his supposedly deep verses seem watered down compared to Frank’s heady standard. And while Drake more or less popularized singing/rapping (Lauryn Hill did it way before, just saying), Frank has proven he can do everything Drake does, and more. In the end, Frank’s artistic passion and impossibly high self standards make for deeper, more challenging, and objectively better music.

Blonde concludes with the nostalgic “Futura Free”, in which staticky audio clips of Frank interviewing his brother and friends float above the dreamily hypnotic electric piano ostinato that becomes a theme throughout the album. As evidenced by the title of his first release, Nostalgia, Ultra, Frank is forever looking backwards. He cherishes things from his childhood, like the sound of a Playstation starting up, or Michael Jackson, or the goofy laughter of friends. Maybe his spiral staircase is just another tangible thing he can remember fondly years from now. It’s hard not to revere the past; there is something profound about knowing every moment that passes will never happen again. Frank, like many others, combats this relentless ticking of the clock by capturing memories and preserving them in art, which might resemble stagnation, but in reality is something closer to creation. Fulfilling a central purpose of art, Endless and Blonde inspire us to create, and as Frank notes in a personal essay from Boys Don’t Cry, the act of creating should be cherished just as much as the final product.