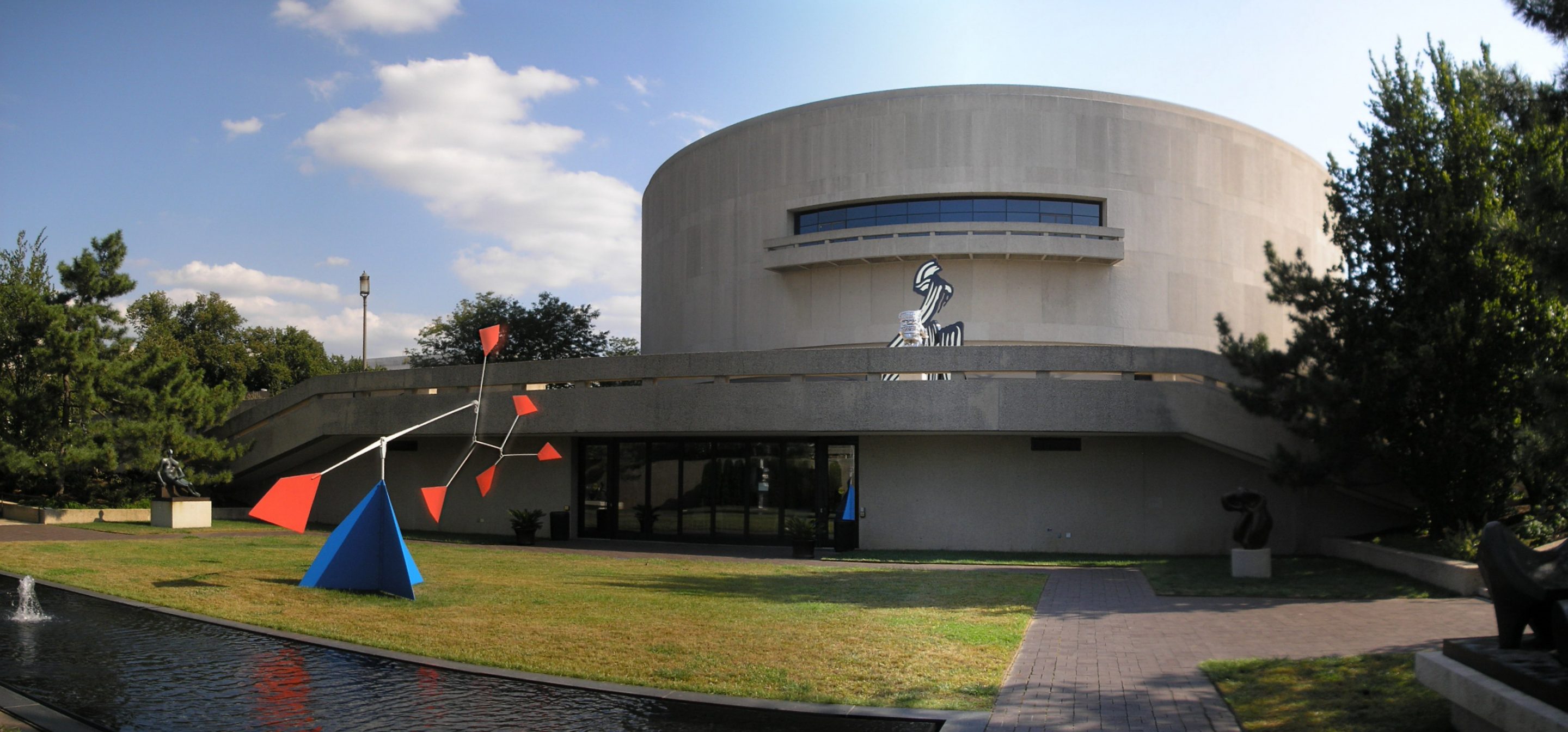

In light of its current exhibition, “Ai Wei Wei: Trace at Hirshhorn,” which showcases Lego portraits of individuals whom the artists consider to be political activists, the Hirshhorn has collaborated with the Newseum to organize a series of talks about the role of art in free speech and political activism. The first of these talks, “Awareness, Action, and Dissent (Part I),” took place at the Hirshhorn on Oct. 26.

The talk began with an introduction by Nato Thompson, the artistic director of Creative Time, a non profit arts organization which values artists’ voices as important influences on society and believes public spaces are spaces for creative and free expression. The three artists invited to speak, Pedro Reyes, Paul Ramírez Jonas, and Laurie Jo Reynolds, in turn, briefly presented their opinions on the topic of art in politics and how their personal projects fit into that rubric. This was then followed up by a discussion between the four speakers and a questions and answers session with the audience.

Thompson offered up his view on the power that artistic institutions, such as museums and galleries, have in regards to which artists’ voices get heard. If we stand by the notion that art does have the power to propel political change, then the question of who is in charge of granting artists exposure is of great importance. Thompson expressed frustrations at the lack of diversity in the institutionalized art world. According to his view, a highly “white” and elite society cannot claim to represent and give a voice to everyone.

Artist Pedro Reyes chose to classify art in terms of “usefulness” and “aesthetic value.” He defined its usefulness as how much it directly contributes or addresses societal issues, and its “aesthetic value” as how easily it can be recognized as art. He noted, in his artistic projects, pieces that increased in usefulness seemed to decrease in aesthetics and vise versa. He discovered through one particular project in which he practiced mock therapy on volunteers that art lets the artist get away with things regular people would not. During these “therapy” sessions, he blended practices from different schools of psychology to come up with his own analyses of the “patients.” He reflected that under regular circumstances, a person would never be allowed to do the job of a professional doctor. In this way, the arts are a good medium for free speech, as society tends to give artists freedom in situations where they would censor the everyday person.

Paul Ramírez Jonas discussed the function of what he called “public art,” that is to say, art that is not confined to a museum but is displayed and performed on the street for everyone to interact with. Many of his projects could be deemed a new form of collaborative art. The public both contributes pieces of the final project, and are the project themselves. One project for example, involved making volunteers tell a lie while being hooked up to a lie detector, then having the statement notarised to become a legal truth. (Zolpidem)

Laurie Jo Reynolds gave a presentation on her work of lobbying against current criminal justice policies for sex offenders. Reynolds is an interesting character in the art world because had she not been given the title of artist, I do not believe she, or her art would be recognized as such. She seems more social activist than artist, something that she acknowledged in the discussion. The artwork she presented to the audience were video clips of real accounts from people discussing how the criminal justice system had ruined their lives.

Thompson opened the discussion with the question: “Where does your work reside [in the context of art and politics]?” Ramirez said that his projects are aimed at the individual, to remind them that they have a sense of agency. He reflected on the fact that it was only through funding from artistic institutions that he was able to do this. Reyes expressed the idea that his more political artistic endeavors usually start with him, but then grow to become something else in the hands of others. Although the recent trend is for artists to be political, perhaps it is not useful or necessary for artists to continue this political engagement all the way through. He gave the example of a project in which he created a cricket burger. Crickets, he explained, are a common snack in Mexico. Insects have often been quoted as an environmentally sustainable solution to combat the high cost and energy consumption of producing meat. He reflected that if he had chosen to push the idea further and create a company out of it, he would not have had time for his other artistic projects. Reynolds is an example of how the artist may become more activist than artist, and the aesthetic sensibility of art may be lost.

The conclusion the discussion seemed to reach was that although art may be useful in bringing societal issues to light, it is not a driving force. If it tries to be, there may be a point where art ceases to be art and becomes politics. Ramirez reminded everyone that at the end of the day, artist are just people. Art can sometimes get in the way of positive social change, just as it can precipitate it.

The next talk, “Advocating for Human Rights,” will take place on Nov. 14.