As the Voice nears our 50th anniversary in March 2019, we are looking back at our history, alumni, and life after the Voice.

Jason Berry (COL ’71) arrived at Georgetown in 1967, during the height of the Vietnam War. Lyndon B. Johnson was president and the university, like the rest of the country, was gripped by fiery anti-war protests. Students were angry and looking for an outlet.

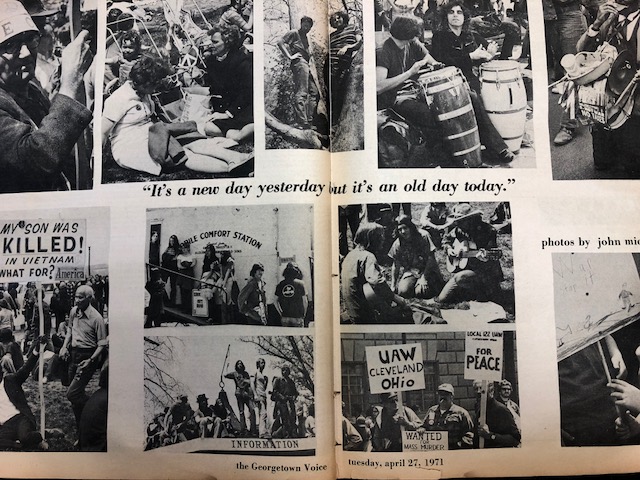

The Georgetown Voice was their answer. In 1969, Stephen Pisinski (COL ’71) and a few friends, frustrated by The Hoya’s reluctance to cover the war and other off-campus news, split from the newspaper to create their own.

“Our editorial policy will view and analyze issues in a liberal light. We shall not limit our editorial content to campus topics,” they wrote in the Voice’s debut editorial in 1969. “We promise to present and analyze national and local issues of concern to the students, whose concern should spread beyond the campus.”

Berry was one of these early members of the Voice, writing film and theater reviews. Since then, he has produced a film on jazz in New Orleans and written a comedic novel.

But it was during his career as an investigative reporter in the ’80s when he wrote the story that changed his career: His report on sexual abuse in the Catholic Church in New Orleans broke the story before it had become the nationwide conversation it is today.

Before that, though, when he first arrived on campus 50 years ago, Berry was new to activism and overwhelmed by wartime protests. “I was just a guy from New Orleans,” he said. “I wasn’t used to things like that.”

The politics at the time were heated because they were deeply personal. Berry and other male students were eligible for the draft. At any moment, they could be selected and required to enlist.

“I remember in my junior year, sitting around a kitchen of a house on Calvert Street, and we listened on the radio as they called out the numbers in the lottery,” Berry said. “If you got a low number you had to register for the draft.” His number—in the 300s—was high enough to spare him.

The heightened political tension on campus during those years was unavoidable. Student voices grew louder and more radical. “It was a very politically charged environment. The combination of civil rights and the war created an atmosphere of great intensity,” he said.

Although Berry opposed the war, he didn’t consider himself the most radical voice on campus. He laughed as he recalled the irony of poring over Dante and Shakespeare for his English classes and then taking to the streets afterwards to protest the establishment. “I guess you could call me a moderate radical,” he said.

Everyone was talking about politics all the time, Berry said. They wrote about politics, too. He remembers the strength of student journalism then. Vietnam helped create the Voice, and it also strengthened the readership of other outlets.

“I had the impression that a lot of students read those outlets,” Berry said. “You read the student press to learn what was going on in your own world.”

Martin Yant (SFS ’71), another early Voice member, recruited Berry to write for the publication. Berry often wrote for the university’s literary magazine, Georgetown Quarterly.

In 1970, the administration slashed student media budgets. Several publications merged with the Quarterly—which still “failed to come out quarterly,” according to the 1971 yearbook. Others did not survive at all. The Voice itself hardly made it through.

“It felt the lack of financial backing to the point that it opted for a cheaper format, so that it does not become a Hoya-Voice,” the 1971 yearbook read. Despite rumors of a merger at the time, the Voice has continued independently ever since.

Berry continued to pursue journalism after his start at the Voice. After graduating, he went to Mississippi and worked as a press secretary for Charles Evers’ unsuccessful bid for governor.

He published a book on that experience in 1973. By the age of 24, he had returned to New Orleans and started a career as a freelance journalist, covering arts and politics in the city. Since then, he has worked as an independent writer.

But his life as a freelance writer in the early ’70s would be impossible now, Berry said. His apartment in New Orleans cost $75 a month—less than $500 today. He could survive on one article a week, and he found comfortable success in his work. It was this independence, he said, that allowed him to write the story that changed his career.

In 1984, a friend of his from high school, who worked as a lawyer, granted him access to the trial documents of a priest accused of sex abuse in Lafayette County, Louisiana. The series of articles he wrote spurred by those first documents was the first well-publicized case of sex abuse in the Catholic Church in the U.S. The stories shocked the nation and launched Berry’s career.

Berry could never quite escape the story. Priests and nuns approached him with tips on other cases. In 2002, The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team published their famed findings of sexual misconduct and abuse within Catholic churches in their area, and spurred Berry to investigate. “I sort of came out of retirement on that issue. I got a contract very quickly and did a second book,” he said.

Berry felt obligated to pursue the story. “My life probably would have been happier if I had just kept writing about politics and culture in New Orleans,” Berry said. “But the story kept deepening and widening, and it became such a media narrative. Almost like a tsunami, which is where we are right now.”

Now this wave has reached Georgetown. The university has faced criticism from students for not revoking the honorary degrees of Cardinals Theodore McCarrick and Donald Wuerl— both of whom were involved in high-profile sex abuse scandals in the Church this summer. Berry wrote a piece for the Washington Post on these scandals in August.

While it’s an important conversation, Berry explained, it’s not the only subject he cares about. He has dedicated much of his career to writing about New Orleans, covering its rich arts and music scene. Just as the national spotlight falls once again on the Church, his book on the city he loves is being released.

“There have been two major stories of my life: the city of my birth and the church at which I was raised,” Berry said. “And right now, they’re colliding.”

This collision of stories has always been a vital part of the Voice’s own philosophy. The publication was founded to cover both local and national politics, to investigate art and culture as well as political scandals—a dichotomy Berry has embodied throughout his career.

Berry emphasized the importance of the student and local journalism in papers like the Voice. “Journalism is going through a revolution with so many print outlets really being starved for advertising,” he said. “While the web has indeed opened up a seemingly endless array of outlets, it’s so important to have intelligent, critical commentary not just of city life, but life in small towns.”

But Berry remains optimistic about the profession he began 50 years ago with the Voice.

“I don’t think journalism is going to simply fade,” he said. “The important thing is not to give up.”