I listened to Earl Sweatshirt’s Doris (2013) for the first time during my junior year of high school. I had just moved from the coast of South Texas to Arizona. I was about two months into the school year and living in a bedroom with my younger brother, doing marching band in triple-digit weather four hours a day, and still had approximately zero friends after a long summer of having approximately zero friends. I remember sitting on the carpeted floor of my shared bedroom in a moment where my brother was gone, actually truly alone. I, of course, had been feeling lonely a lot since moving, but there is a stark difference between feeling lonely in a room full of people and feeling lonely while you are by yourself. There is a specific kind of comfort in feeling exactly what you are supposed to be feeling when you should be feeling it, even if that feeling is not positive. It was then, in this softer lonely moment amidst hundreds of harder ones, that I put in my headphones.

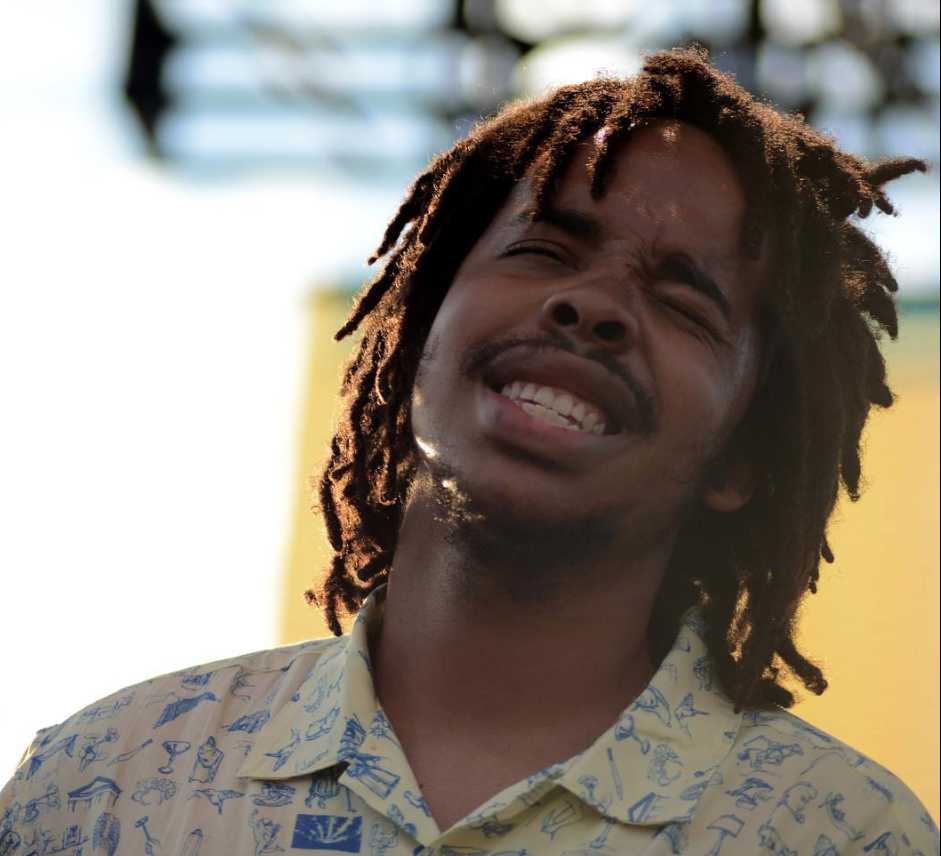

Thebe Kgositsile’s most recent release, under his long-standing stage name Earl Sweatshirt, Some Rap Songs (2018), is a 24-minute invitation into the life of someone who has been working to get better. It is no secret that Earl’s past discography is marked by his struggles with anxiety and depression. There is sadness, and then there is Sadness: a more persistent and constant haunting. Doris and I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside (2015) are both about Sadness. They are albums for rainy cold days and late nights in living rooms with just your closest friends, talking until the sun starts to rise. Some Rap Songs is less a chronicling of a Sadness than it is the reality of someone trying to recover. Marked by brief moments of hope and something resembling escape, Earl finds fleeting solace in nostalgia, friendship, family, substances, and a coming future he is pushing to build himself.

Dark and murky production marked by loops and well-sampled jazz and spoken word, Some Rap Songs lives up to the stark simplicity of its title, maintaining much of Earl’s previous aesthetic, but stripping away bells and whistles. Almost a response, perhaps more accurately an intervention on the SoundCloud era of rap we have entered, Earl elevates the form, committing to a lo-fi but detailed and meticulous construction of an album. From the brief pauses in the instrumental of “December 24” to the occasional glitches and pitch shifts of “The Bends,” each moment feels precisely curated. Beats are looped, forcing Earl to rely strictly on lyricism rather than beat switches to communicate and entice. Particular moments are chosen for off-beat flows in order to highlight a line or word. The album asks its listener to search for brief idiosyncrasies, meant to point you towards not only the intended point of each track but the overarching intention of the album. With a lack of hooks or even choruses, Earl’s songs reward the intent listener with recurring themes and images across the cacophony of verses that make up the album. These choices can ostracize the casual listener who might find Some Rap Songs somewhat messy or difficult to connect to on a cursory listen, but the transitions between tracks are so smooth, the instrumentals so jazzy and shrugging, someone simply looking for atmosphere could find immense pleasure in this absolute unit of an album.

It is impossible to talk about Some Rap Songs without addressing its dialogue concerning family. Earl’s first studio album, Doris, is marked by the death of his grandmother and exudes immense grief from its first track. Some Rap Songs is similarly inextricable from death with Earl’s father dying in South Africa in January of last year, just a few months before the album’s completion. Rather than excavating grief throughout, the death hangs most heavy in the latter half of the album. Perhaps the most emotionally moving track on Some Rap Songs, “Playing Possum,” samples Cheryl Harris, Earl’s mother and the Chair in Civil Rights and Civil Liberties at UCLA Law School, as she delivers a keynote address. This audio is spliced together with a 2009 recording of Earl’s father, the poet Keorapetse Kgositsile, reading his poem “Anguish Longer Than Sorrow.” Each of the recordings evokes and invokes images and feelings of home, family, and the intersections of memory with reality. It is a painful and beautiful moment on the album which interrogates Earl’s relationship with his parents without requiring a moment of lyricism from him at all. Instead, Earl opts to eulogize his father’s passing in “Peanut.” A brief and sorrow-filled minute and fourteen seconds, the track depicts the same complicated relationship Earl puts on display throughout the album concerning his family and what they mean to him, particularly his father, who he now must grieve in the midst of this attempt to find solace beyond and within depression.

The final track, “Riot!,” succinctly and perfectly summarizes the album. A simple, looping instrumental, the short song is built using samples from the South African jazz musician Hugh Masekala. Masekala died just a few weeks after Earl’s father, with whom he was close friends. “Riot!” makes use of a Masekala track of the same title (sans the exclamation point), layering together stripped instruments into a jaunty, yet reverent low-fi harmony marked by bright trumpets and plucked guitar. As the loop progresses, it begins to break down, grinding into a brief sputtering before slowly succumbing to silence. This is the balance of the album: the hope in the face of something larger, and the submitting to its power. There is the getting better, then there is the grief, and then there is the hope for getting better again.

When I am Sad, I don’t want music about triumph or happiness or how someone else made it through. I want to hear someone say that they too are in the dark, but have some flickering sense of possible coming hope. I want to hear someone say that they hope the hope is eventually coming because that’s all they feel they can do, because sometimes that’s all I feel I can do. Sometimes, when you are in the dark, the idea of a light at the end of the tunnel is just offensive. Sometimes, when you are in the dark, you just want someone else there with you, saying, “It looks like there’s no way out and probably there won’t ever be, but maybe if we sit here long enough that will change.” This is what Earl Sweatshirt does in Some Rap Songs. His positivity feels authentic: always on the edge of disappearing, but never quite gone.

I listened to Earl Sweatshirt’s Some Rap Songs for the first time at 3:45 AM on the day of its release. I have been having trouble sleeping lately and I’m not sure why. It has been a weird semester for me and for a lot of people I know. Last week marks me having lived on this campus longer than I lived in Arizona. I think I am doing better here than I did there. Here, I feel like I am in a good place until I am suddenly spiraling. I am in a spiraling time now, I think, and feeling lonelier than I have been. Listening to this album though, the Sadness softens, and sleep starts to come. Some Rap Songs is not a hand pulling you toward the light, but a promise that others are also looking for a light that they can’t see. Sadness stops being a dark mark and instead becomes something you are supposed to be feeling exactly when you are feeling it. I won’t pretend that I suddenly don’t feel lonely because of listening to someone I’ve never met rap about how they are also Sad and anxious and struggling to see a way out, but, as cliché as it is, I do feel less alone. I do feel hope. I do feel like things are getting better, or at least they one day will.