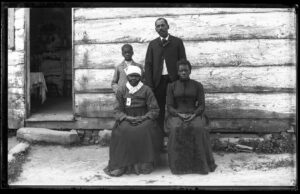

Georgetown students are voting on a referendum to add a $27.20 per semester fee to fund projects benefiting the descendants of the 272 enslaved people sold by the university in 1838. The Vote No campaign, led by Sam Dubke (COL ’21) and Hayley Grande (COL ’21), has been sharing quotes on Facebook of a Baton Rouge descendant, Jessica Tilson, who opposes the referendum.

Individuals on both sides of the referendum have spent the past semester trying to convince students of their perspective. The GU 272 Student Advocacy Team, the group of undergraduates who brought the referendum to the GUSA Senate, have been tabling in Red Square and held a town hall on April 3 to answer student questions that members of the “No” campaign participated in.

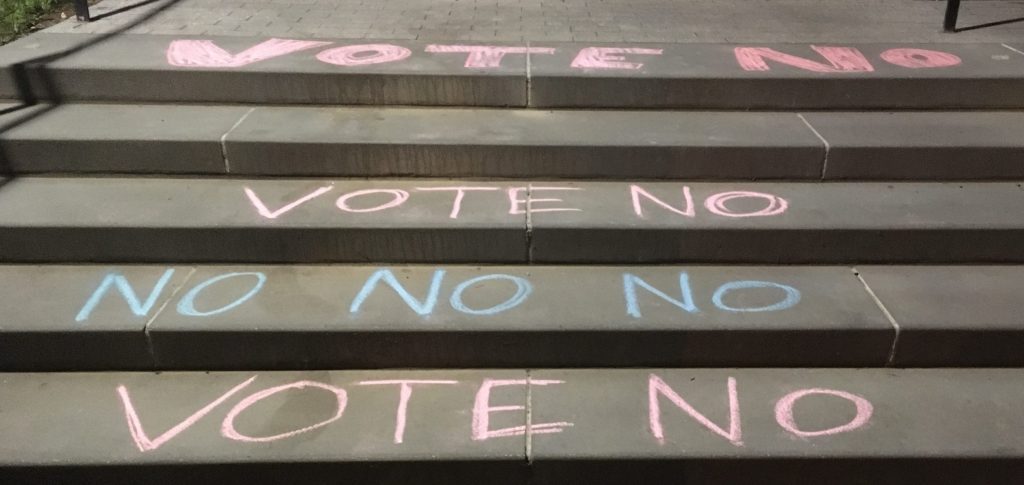

Chalk from the No Campaign near Red Square

The “Yes” campaign and GU272 Advocacy team has several members of the descendant community, including current students at Georgetown, in its group, but Dubke said he did not believe descendants had been given greater input. Dubke wrote in an email to the Voice, that the No campaign takes issue with the fact that the referendum denies a vote to descendants who are not current Georgetown students, and wishes the descendant community had been given greater input.

“We wish that time had been taken to actually interview the bulk of descendants about what they want Georgetown students to do in response to our shared history,” Dubke wrote.

The GU272 Reconciliation Board of Trustees will be made up of five descendants and five students. The descendant members will serve a five year term and will be elected at the annual descendant reunion.

Tilson takes issue with the mandatory nature of the fee, and what she percieves as the hypocritical nature of compelling students to pay even if they do not want to. “The Jesuits forced my ancestors to come here, and how can I say that forcing someone to do something is wrong, but then I turn around and agree with forcing you all to pay us,” she said.

Tilson believes setting up a system to donate would have been a better option. “If it took them 15 years to raise $200,000 well guess what? At least I know it came from the heart,” Tilson said.

At the town hall last week, descendant and supporter of the referendum Mélisande Short-Colomb (COL ’21), said that she is glad that Georgetown students have an opportunity to vote yes on the reconciliation fund. You have the opportunity to vote on it, she said, because “the Jesuits sold my family and 40 other families so you could be here.”

In 2015, student actions led to the university changing the names of Mulledy Hall and McSherry Hall, named after two Jesuits involved in the slave trade. Tilson commended this effort due to the fact that students were able to choose to participate.

The 272 Advocacy Team wants all students to acknowledge the role of the 1838 sale in preventing the university’s financial ruin and allowing them to graduate today with all the privileges a Georgetown degree affords. “We all leave Georgetown with our degree, prestigious accolades, and the potential for social, economic, and professional mobility. As Georgetown students who are implicated in this legacy, we all should participate in returning the capital we gain through our attendance,” the advocacy team wrote in a statement to the Voice.

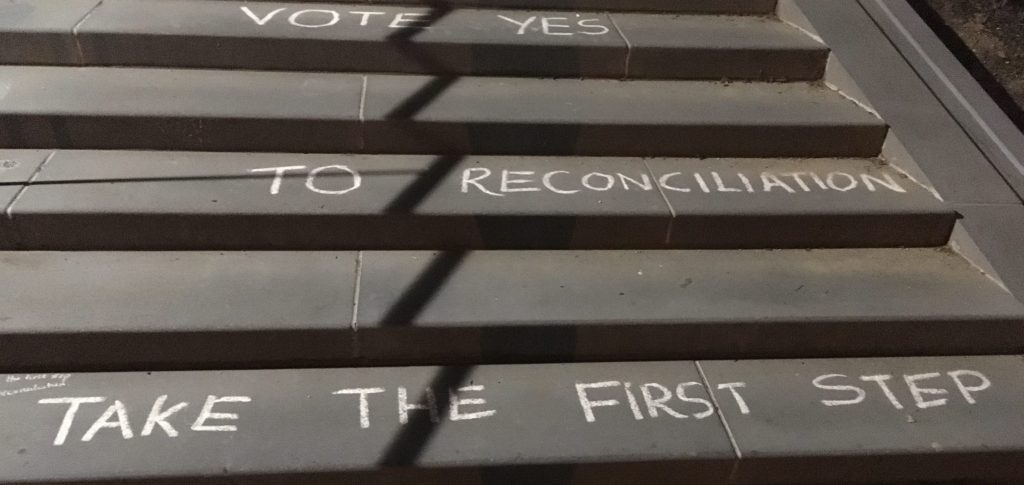

Chalk from supporters of the referendum

Tilson cannot justify receiving money from black students who are descendants of slavery like her. “How can I look at them and say I need you to pay me, for what the white Jesuits did,” she said.

In April 2017, Fr. Timothy Kesicki apologized on behalf of the Society of Jesus at Georgetown’s Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope. Tilson noted that it was the Jesuits, not the students, who apologized, and she feels it is not right for any student, affected by the legacy of slavery or otherwise, to be paying for acts that the Jesuits should be atoning for.

“You decided to carry their cross, and that’s not your cross to bear. That’s their cross to bear,” Tilson said.

She feels the university will see the adoption of the student fee as permission to not commit to reparative justice themselves.

The 272 Advocacy Team counters that they view the referendum as a small step forward. They hope all students will see the referendum as an opportunity to research Georgetown’s history and urge the university and the Jesuits towards further action.

“The referendum is not meant to be a solution or end to this issue and does not present itself as such,” the advocacy team wrote.

Short-Colomb told the Voice after the referedum passed the GUSA Senate in February that she hopes students will pass the referendum and that other student bodies will soon take up reconciliation for their universities’ roles in the slave trade.

“As Georgetown students voting yes on this referendum, we put ourselves in the position of doing what has never been done in this country.”

But Tilson said she wishes that instead of spending their money, students would choose to spend more time engaging with descendant communities. Part of her issue with the referendum is she believes students do not have accurate information about Maringouin, Louisiana, where many of the descendants live, and wants to see more students come to see Maringouin for themselves.

Several groups of students have taken trips to Maringouin over the past year, as part of the advocacy team and Georgetown classes. Yet Tilson said the language in the Act of Referendum portrays the town that she grew up in as an underprivileged community, as it includes that “only 14 percent of residents have attained a bachelor’s degree or higher and the median income is $36,518.” These numbers are validated by data from the Census Bureau, which also highlights a racial disparity. In 2016, 34 percent of the white population in Maringouin earned a bachelor’s degree or higher while only 9 percent of black residents achieved the same.

Tilson believes the language of the referendum degrades Maringouin’s population and ignores the reality that a majority of the descendants from Maringouin have degrees but must move away to get a job.

“There are no jobs there. I mean you have a degree in microbiology, what are you going to do, work at the gas station?” Tilson said.

The advocacy team wrote that the idea there has been a misleading narrative about Maringouin’s economic status “misconstrues both the point of reparative justice and the referendum.”

“The reconciliation fund is not meant to be solely allocated to residents of Maringouin, nor is it meant to address historical disenfranchisement as an economic phenomenon unique to one town,” they wrote. “The advocacy team recognizes that descendants are not a monolith and there is not one experience that can encompass all descendant experiences or identities.”

But Tilson hopes Georgetown students will vote no. She said she is also against the referendum because she feels it puts another price on her ancestors. She said it’s not possible to make that judgment and still respect them as human beings.

“I’m against that because my ancestors’ whole entire life, they was viewed as a dollar sign. A dollar sign. They weren’t a human being, that wasn’t a person, that was $1500, that was $200, that one was free because it didn’t do anything, that was a baby, it can’t work,” said Tilson. “Whatever Georgetown gives me, that’s what I’m going to have to say my ancestors were worth.”

The referendum will pass if affirmed by a simple majority of the voting population. It will then have to be approved by the Georgetown Board of Directors for the fee to be implemented.

This article has been updated. Its original headline was “Both Sides in 272 referendum make final pitch as election opens,” but was changed to reflect the focus on Tilson’s viewpoint. Additionally, Short-Colomb’s quotes and a the GU272 advocacy team’s statement on allocations of funds to Maringouin have been added since the initial posting.

[…] Citing a Misrepresentation of Maringouin, This Descendant Opposes the GU272 Referendum The Georgetown Voice […]